FOLK ART, HERITAGE AND TRADITIONAL PROFESSIONS

This project wants to intensify the campaign to prevent traditional industries from extinction.

CLAY POT FILTER FROM LOCAL POTTERS

HOUSEHOLD FILTER JIBON (LIFE)

CONTENT

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Oldest University in Asia, Terra Cotta Remains

- 3. Pat and Patua important audio-visual mediums in educating the masses since immortal

- 4.Gazir Gan, Pat, puthi Pat

- 5. Glorious Heritage is going to Perish

- 6. Health Hazrads from Modern Household Articles

- 7. Pottery Faces Extinction

- 8. Balcksmiths Face Extinction

- 9. Traditional Jewellers on the Wane

- 10. The Lost Art of Metal Casting

- 11.Satranji : Weaving for a cause -Rugs steeped in history

- 12. Bamboo-based cottage industry faces extinction

- 13. The fading trade and the fading away shankharis

- 14. Khadi Reviving the Heritage

If you visit slums of Dhaka, you'll find talented professionals such weavers, potters etc. who are now daily labourer or beggars. These people have provided thousands of years sustainable products for generations but now plastic and aluminium products have displaced them. Thirty percent of about 15 million population in Dhaka city are recent migrants from the rural areas of Bangladesh, but unlike many other Third World cities this influx was not accompanied by industrialisation.1. INTRODUCTION

The production of pottery is one of the most ancient arts. The oldest known body of pottery dates from the Jomon period (from about 10,500 to 400 BC) in Japan; and even the earliest Jomon pottery exhibit a unique sophistication of technique and design. Excavations in the Near East have revealed that primitive fired-clay vessels were made there more than 8,000 years ago. Potters were working in Iran by about 5500 BC, and earthenware was probably being produced even earlier on the Iranian high plateau. Chinese potters had developed characteristic techniques by about 5000 BC. In the New World many pre-Columbian American cultures developed highly artistic pottery traditions. The Indian sub-continent including the area which includes Bangladesh was also famous for pottery

Regardless of time or place, basic pottery techniques have varied little except in ancient America, where the potter's wheel was unknown. Among the requisites of success are correct composition of the clay body by using balanced materials; skill in shaping the wet clay on the wheel or pressing it into molds; and, most important, firing at the correct temperature. The last operation depends vitally on the experience, judgment, and technical skill of the potter (Prodip Aich, The Independent, October 13, 2003).

From third century B. C. and twelfth century A. D. pottery, terra cotta figurines and plaques were most abundant in Bangladesh (Mahmud. F.,(1987). The earliest specimens of pottery are those of the Northern Black Polished Ware. This pottery spread into Bangladesh from the north later than fourth century B. C.

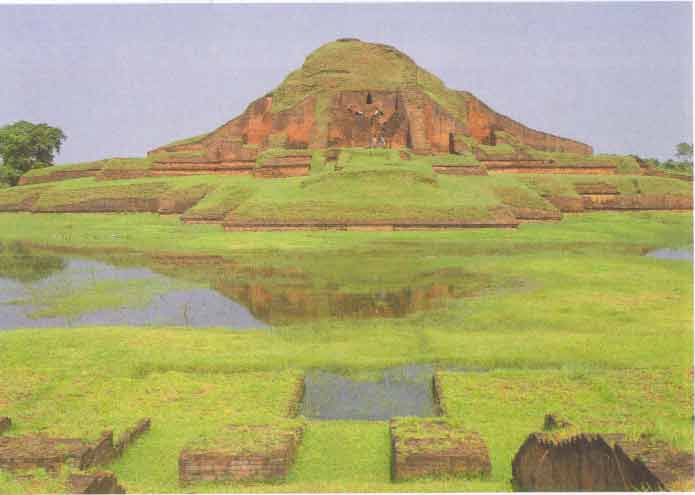

The most unfortunate present history is that the old wall of Mahastangarh (300 B.C.) is destroyed by constructing a new wall by the Archaeological Department. When we asked them, why they did it? The reply was that because there was some money and we tendered to construct walls on it!!!. Besides, the ruin is not protected properly. During dry season visitors from all over country use it as a picnic spot!The discovery of specimens of pottery at Mahasangarh, north Bengal from third century B. C. to sixteenth century A. D. reflect the evolution of pottery in cultural setting. Pottery represents the largest single category of antiquities at Mainamati (SE of Dhaka). The subject matter portrayed in the Mainamati terra cotta plaques is overwhelming, it includes almost everything that can be found in the life and imagination of the Bengal countryside.

Varied specimens of pottery have been discovered at Pharpur, N. Bengal (ancient residential University of Bangladesh). There are above 2000 terra cotta plaques still embellishing the outer wall of the Pharpur temple.

Mahasthangarh turning into farmland

Mahasthangarh, one of the country's oldest archaeological sites, is gradually becoming a farmland due to government apathy. Instead of protecting the 2,374 year-old site, which hosts an ancient capital city named Pundranagar, local people have been seen cultivating winter vegetables, onions, rice and other crops on more than one square kilometre of land there. The 15 sqkm site is surrounded by villages. Residents say precious artifacts, including gold coins, jewellery, utensils and inscriptions, were dug out and smuggled away from the site, which is located 18 kilometers away from the northern town of Bogra. "If the government does not take steps soon to establish authority over this land, we will no longer be able to protect the site," said Curator of Mahasthangarh Museum, Md Abdul Zabbar. While unwarranted farmers have taken over one sqkm of land, the government has only acquired less than 10 acres of land in the last several years. Such apathy has encouraged some to build houses and steal bricks thousands of years old to construct their houses. According to land records, farmers still own over 800 acres of land in the archaeological site, archaeological officials said. But since the government has not taken any steps to acquire the land, they still farm on the area and cause damage to the site by taking away bricks and other materials, local people claim.

"We are doing everything within our means to save it. We have submitted many projects but the government could not do anything due to lack of funds," said Abdul Khaleque, regional director of Rajshahi Division. A Unesco official said the government has been preparing a proposal asking Unesco to announce Mahasthangarh as a world heritage nomination and provide financial and technical help. "After receiving the government proposal, the Unesco experts will decide whether this site should be marked as a world heritage site or not," notes Shahida Parvin from the cultural desk of Unesco.

During a recent visit, this correspondent saw that many new houses have been built inside the site and people have been taking away the bricks of the archeological site to construct their own buildings. Aaliboddi Mia, a local who was seen carrying two baskets of ancient bricks, believes he has the right to take the bricks. "We have been living in that area for generations and we own these lands," Mia points out. He explains how he got the bricks, " I got it by digging the land. I will make a wall using mud and these bricks at my house."

Some other people have been seen blissfully cultivating vegetables there. "This land is high and we were not affected by the floods. In this season we already sold radish, potato and pumpkin and made Tk 21,000 profit," said Tofazzal Hossain, while irrigating his vegetables with a shallow pump. Another local cultivator, Mokless Hossain, said they have been cultivating vegetables there for a couple of years. An excavation of the site has been underway since 1993, as part of an academic exchange scheme between Bangladesh and France. Shafiqul Alam, chief of the excavation team notes that Mahasthangarh is an open site and its land is public property. And he believes cultivation is not a problem for the site.

"It would take a lot of money to acquire all those lands. But the government do not have that money and so we cannot do much," Shafiqul Alam points out adding, "if the farmers do not dig out the site very deep, it would not be a problem." Perched on the western bank of the Korotoa River, Mahasthangarh is one of the oldest settlements in Bangladesh. Discovered in the early 1930s, this one-time affluent city was buried under the soil and is said to hold scores of priceless artifacts (Pinaki Roy, November 28, 2004) .

The Pala Kings, who ruled Bengal in the 5th century were Buddhists Many Buddhists Vihara well as other subjects. Since the Buddhists wanted to live in peace and had respect for other religions convinced the Pala emperor Dharmapala to convert himself to Buddhism from Jaina fath. Intermingling of the Hindu, Jaina and Buddhist faiths are evident in the arts and sculptures recovered from the site of this Vihara.

At Paharpur some terra-cotta seals bearing the name of the vice chancellor, Sri Somepure, a member of the second ruler of the Pala dynasty, of the oldest university in Asia named as "Somapura Buddha Vihara Viswabidyalaya" (Khatun, 1997). The University used to teach theology, grammar, logic, philosophy, fine arts and visited by famous scholars. The residential university enrolled students free of costs and their clothing and food were also free. About one hundred adjacent villages supplied food and clothing for about 2,000 students living in 177 rooms in a 21 acre fortified complex area. Students from south-east Asian countries like Korea, Mongolia, China and Tibet came here to receive the superior quality of education provided by this University. The books preserved in the library were made of parchment paper and palm leaves. But the library was looted and ravaged after the fall of the Pala dynasty (M. Khatun, 1997).

Paharpur Buddhist Monastery (Sompur Bihar) facing ruination

The ancient Paharpur Buddhist Monastery (Sompur Bihar) in Naogaon is in a sorry state. A huge number of terracotta plaques have been stolen from the walls of its temple before and after the declaration of the monastery and its adjacent areas as a World Heritage Site in 1984. A high official of the archeology department said, the famous monastery was facing ruination for lack of proper maintenance and supervision. He lamented that a good number of antiquities were earlier destroyed during excavation work at the site between 1923 and 1934.

Though the department collected some antiquities, it is high time to resist their theft and destruction, he said. Another senior official of the department said that a significant number of antiquities and terracotta went 'missing' between 1990 and 1995. A gang of 'antique lifters' is active in the area, he said. Citing poor security, he said, just a few months ago some miscreants broke open a portion of the iron grills of the temple's boundary wall. "We could not even maintain the sanctity of the World Heritage Site," he said, pointing to the setting up of a cell phone tower in front of the monastery which blocked the natural beauty of the spot. "We reported the matter to the authorities, but to no effect."

The excavated remains at Paharpur represent the largest known Buddhist monastery south of the Himalayas. The gradual deposition of wind-borne dust over the ruins for ages took the shape of a high mound or a hill. Hence the name of the place has probably became Paharpur. Excavations conducted there from 1923 to 1934 yielded a huge number of antiquities including one inscribed copper-plate of Gupta (479 AD), stone inscriptions, stone and bronze sculptures, terracotta plaques, inscribed clay sealings, ornamental bricks, metal objects, different earthen objects and silver coins.

From the reading of a number of inscribed clay sealings, it is learnt that original name of this monastery was Somapura Mahavihara (great monastery) and it was built by Dharmapala (770-810 AD), the 2nd Pala emperor. In 1982 and later, deep digging was conducted in some cells of Paharpur monastery. During digging, one terracotta image head, one copper coin and some other antiquities were found at lower occupation levels. These antiquities, particularly the terracotta image head resembles the features of Gupta sculptures.

Besides these antiquities, the ruins of a vast building having larger rooms (each 16'x13'-6? ) were brought to light. This building was known as the Jaina Vihara as mentioned in Paharpur copper plate. However, to ascertain the feature, further deep digging, investigation and study are necessary. Paharpur monastery measures 922 feet north-south by 919 feet east-west having its elaborate gateway in the middle of the northern wing. It has 177 cells in its four wings around an inner courtyard. The lofty temple in the middle of the courtyard; numerous votive stupas, miniature models of the central temple; chapels; small temples, kitchen and ancillary buildings are very beautiful.

The imposing central temple is cruciform in shape and built high in terraces. The outer faces of the walls of the temple are decorated by terracotta plaques. From the last quarter of 9th century onward the Pala Empire was repeatedly attacked by some foreign kings and one native Kaivarta chief named Divya. Because of repeated attacks Somapura Mahavihara suffered greatly. About the same time Paharpur monastery and temples were burnt by Bangla Army. In 12th century, Bengal was ruled by the Sena kings, who were blind supporters of Brahamanism. From that time on the Paharpur monastery and its temples were gradually abandoned for lack of Royal patronage. The monks and worshippers deserted Paharpur and went to other places (Hasibur Rahman Bilu, 2005) .

The customs and practices of rural life have inspired artisans to create and recreate objects of play, of worship, and of utility. To suit the immediacy of their needs they have used materials which are cheap and redilly available such as clay, wood, brass, bamboo etc.

Puthia Rajbari, once fascinating, is a large complex home to several old Hindu temples and is a testimony to a unified architectural pattern. At the entry to Puthia, formerly a large estate, is a large white stucco temple dedicated to Shiva, modelled on a typical north Indian design and dating back to 1823.

To the left of the main façade of the palace is the Govinda Temple, dedicated to Lord Krishna, which follows a typical Hindu temple shape prevalent in Bengal at the time. It is decorated with delicate terra-cotta panels depicting scenes from the Radha Krishna and other Hindu epics.The antique treasure now stands in isolation across an overgrown playground that bears the hallmarks of neglect. A short evening stay in front of the lonely palace is being close to dark shadows that thicken into night or taking a solemn pause for one fleeting moment when past and present overlap. It's just gazing through time's windows on rediscovering dormant splendour.

The walls of the palace are now covered in aggressive graffiti -- its plaster peeling, windows falling apart and metal laceworks rusting. It wears a defaced look as the college authorities reconstructed the building beyond archaeological norms.

Occupation of the palace goes against the Antiquities Act, 1968 that says any person who destroys, breaks, damages, alters, injures, defaces, mutilates, scribes or writes or engraves any inscription or sign on antiquities is punishable with imprisonment up to one year or with fine or both.

But who is going to "bell the cat"?

The Unesco yesterday (29. 09. 04) called for raising mass awareness about the rich cultural heritage sites in the country. "Bangladesh is a resourceful country because of its rich cultural heritage and has got a bright future... but it needs to preserve those heritage sites," Unesco Representative Wolfgang Vollmann told a press briefing in the city. He said identification of 355 national cultural heritage sites is only a tip of the iceberg; thousands of similar others need proper attention (Daily Star, September 30, 2004).

Prospects of eco-tourism and Buddhist heritage tourism in Bangladesh

357 archaeological sites are under any porotection

Three hundred and fifty-seven archaeological sites, including the world heritage sites such as the Paharur monastery and Bagerhat Shat Gambuz Mosque, having potential of becoming tourist spots, are either vulnerable or unexplored. The sites are under the scheme of preservation, conservation and presentation of the Department of Archaeology. But there are neither any physical protections nor any measures to make the places attractive to visitors.

Archaeological sites such as Paharpur, the largest Buddhist monastery in Bangladesh, Mahastangarh, the oldest, Mainamati, the seat of the lost Buddhist dynasties, mosques, monuments, temples, shrines, and zamindars' palaces like unprotected. The Department of Archaeology assistant director, Md Khalequzzaman, told New Age they had engaged people in maintaining the sites, but most sites such as temples and mosques are still used by the local residents. He said most of the sites are in remote areas where no physical communication and transport are available; besides, such sites are occupied by the local influential people.

Lack of funds, manpower and lack of awareness among the public of archaeological values were some major problems they face. A survey of the department says there are more than a thousand of archaeology sites, other than the 357, in Bangladesh. A number of Buddhist monasteries were built in this region between the seventh and the twelfth centuries. There is an account of the famous Pandita Vihara of Chittagong in the Tibetan Chronicle, which remains unidentified as yet. Vikrampuri Vihara at Rampal in Dhaka, Agrapuri Vihara at Agradigun in Rajshahi, Jagaddal Vihara at Jagaddal in Rajshahi, Kanka Stupa Vihara of Pattikera at Maynamati in Comilla, Po-Shi-Po Vihara in Bogra have been marked as tourist spots by the Parjatan Corporation. The Bangladesh Tour Operators' Association president, Faridul Haque, said, 'Our archaeological sites have huge potential in tourism sector.' He said not only proper conservation, but also proper records of history and its publication also necessary. (New Age March 26, 2005)Shiva Temples in Tarash upazila of Sirajganj is facing the risk of destruction

The invaluable treasure of ancient terracotta artworks on the walls of the twin Kapileswar Shiva Temples in Tarash upazila of Sirajganj is facing the risk of destruction as the temples have long been in a dilapidated condition.

Although a large number of terracotta decoration pieces have been stolen or misplaced over the years, the brick-built temples built in 1630-35AD still showcase an ample amount of such terracotta plaques. But the authorities have not yet declared them as a protected site.

A few senior officials of the Archaeology Department said several proposals in this regard have been sent to the ministry concerned since the country's independence, but to no avail. Nor have the ancient temples been renovated for the last 300 years. According to two Sanskrit inscriptions, Zamindar Prabir Balaram Roy renovated the temples in 1714 using bricks and other building materials.

An official of the Archaeology Department said there is no plan to declare the site protected or start any conservation work soon. Debendranath Ghosh, a septuagenarian resident of Tarash upazila, said he saw over 100 stone statues in the temples in his youth.

Another Tarash-resident, Tapan Goswami, said, "I have seen a large number of statues in the two Shiva temples and other temples in the area in my boyhood, but they have been stolen after the Liberation War." A survey conducted by the Archaeology Department 10 years ago revealed that at least 200 pieces of terracotta plaques were stolen or misplaced.

Tarash Police Station Officer-in-Charge Afzal Hossain said there are police records that a huge number of statues, terracotta plaques and other relics have been stolen from different temples in the area. "The police have so far recovered six stone statues from different areas and handed them over to the Archaeology Department," he said (Daily Star, January 12, 2008).

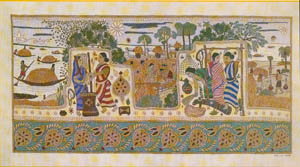

3. Pat and Patua important audio-visual mediums in educating the masses since immortal

There is a very deep cultural link the Indo-Gangetic civilisation, such as that of terra-cotta, cloth and natural fibre like jute, "shola" and beetle nut bark fibre, which are on the verge of extinction. These items go back to as much as 12 centuries. The Moenjodaro link which is visible in our terracotta dolls and toys go back to 3,000 years. Not only has that history been forgotten but the realisation that they are diminishing is that within two decades they'll be there no more. "One craft in particular which has suffered as recently as in 15 years is the type of painted scroll called 'Ghazir pott'. Ghazi is a 'pir' recognised both by the Hindus and Muslims, by the woodcutters, honey gatherers, fishermen and boatmen in the Sundarbans. They invoke the Ghazi pir, the tiger personality who protects the people who enter the jungle."

The 'Ghazir pott' is a series of folk stories told by the village men of the bravery of this man who protected them from tigers. Ghazi, she said, is sacred to the Hindus too as they have a similar personality whom they called 'Shatta pir' but he rides a leopard while Ghazi rides a tiger and both carry symbols in their hands."

One important reason for the diminishing of crafts is that the metropolis dwellers are not paying according to the demand of the producers. When the villagers are putting the products into the market the price is cut to half and bargaining goes on. The elite are least bothered while the middle class like the items and wish to use them at home but unless one is a connoisseur of art the people of the upper echelons of society have forgotten village crafts altogether

"People are ready to pay a high price for painting but they are not ready to pay for a craft that has taken six months whereas the painting may have been done in three days. When a woman has worked on her handicraft on an authentic design for half a year she has the right to ask for more". "Karika" products are art crafts and not just handicrafts, she stressed. For this reason the theme of the exhibit had been "Know Bengali cultural roots."

The reason why our standard has fallen is because the rural artisans have difficulty in marketing their products. I have sometimes gone to a source, following a 15 year-old documentation, and then discovered that in Rajshahi where 'Shokh hari' was being done village-wise is now confined to a few solitary houses. Similarly the makers of blanket from lamb's wool cease to function as before and take up other means of income generating sources. I found only an old widow still pursuing that craft." Chandan said that the entire Bangladeshi scenario is the same. He said that the folk art craftsmen have abandoned their old skilled work due to lack of demand in the market and plastic for instance has replaced clay. The only exception, he pointed out, was Naogaon where nine instead of four families are following a 'sholar' craft making birds and other items since the last 15 years. Even there is a problem as the craftsmen got the material for nothing but now the landlord are charging them a fee for the raw material, Chandan said (Daily Star, October10, 2004).

Kumar or potter family are found all over Bangladesh. The elaborate terra cotta tile works display enormous sweep and dedicated Kumars.

In some communities of kumars make clay pots, vessel for cooking, storing water etc. Other sub-castes fashion figures in the shape of animals, birds, humans and children toys. The "Sakher Hari", an earthen pot, painted with images of fish, combs, birds and floral creepers to denote fertility is used to carry sweets for a marriage ceremony.

Ghazir Pott - Oldest Audio-Visual Medium

Pats (Sanskrit Patta) means picture is an ancient folk tradition. Dr. D. P. Ghosh (1980) describes , " Two thousand and five hundred years ago, scroll-painting or panel painting was widely used in many parts of India as mass media for enjoyment, general education and religious practices." Ram pats or Ghazi pats (picture) used by Hindu and Muslims. Pats are held very vertically and painted from top to bottom were shown scene after scene from the epilical stories.pats were produced for educative and religious purposes. They are used as accessories of balled singer.. Patua is a composer, artist and singer. Evidences of this has been cited through the last two thousand and five hundreds years that Pat and Patua were important audio-visual mediums in educating the masses almost corresponding to the gallery lectures of modern museums.

Gazi Pats Ballad:

Jamdud kaludt at

The right and left

The friend of the Jam raja (king)

Sits in the midst

Gazi says: Chase them away

With Gazi's name.4.Gazir Gan, Pat, puthi Pat

Today, many of us are ignorant of Gazir Gaan, Gazir Yatra, Gazir Pat, Puthi Pat, Kiccha-Kahini jari and so on and on. Saymon Zakaria has been travelling to different parts of Bangladesh to find out and let others know of what remains of the indigenous cultural performances, which still survive like the flickering light of a burnt away candle.

Gazir Gaan

The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him.

The Gazir Gaan singers and the instrumentalists took their seats facing north on the square shaped mat. Then commenced the starting ritual. As the lead singer implanted the symbolic icon, Gazir Asha (Hope of Gazi) north of the audience, music played on. Among the musical instruments were flutes, harmonium, juri or Mandira (a small hollow pair of cymbals) and the dhol (instrument of percussion which is not so much in width as a drum but longer in size). After the group instrumental, the lead singer presented a devotional song with his troupe accompanying him in stages.

If you come, Oh Merciful to rescue the destitute / (Merciful) Please take and make me cross

(I) do not offer my prayers, nor do I fast / Please have mercy and make me cross

(I) coming into this world / about you I have forgotten/ under the spell of infatuation . . .

There are altogether 7 Paalas (episodes) in the Gazir Gaan performance:

Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion.

1. Marriage 2. Didar Badshah 3. Dharma Badshah 4. Erong Badshah 5. Taijel Badshah 6. Tara Dakait 7. Jamal Badshah

But the performance commences with the “Fokre Paala" depicting the story behind Gazi and Kalu's becoming ascetics after which continues seven episodes. Gazi is very serious and sincere in his work, while the character of his brother Kalu is more comical and he is the one who creates the humour through his role. Through his jeers and meaningless dialogue and activities he very skillfully takes the audience into the embedded sorrow and depth of the story. Here are some quotes from the "Fokre Paala". After the dance performed by the "Chukris", the lead singer stands up and delivers some introducing words in his local accent.

After the introductory words of the narrator, starts the instrumental and then the Dhua or starting chorus of the narrative passes from the lead singer to his members of the chorus.

Singer starts the main narration of the Fokre Paala of Gazi and Kalu and at the beginning he requests Kalu earnestly to become Gazi's companion in his quest of becoming an ascetic leaving behind the earthly pleasures and luxury. As this song ends Kalu comes up and takes part in dialogue (in verse and prose)based drama with the lead singer. The statements and their replies are rather nonsense, comic in nature and sometimes with the use of indecent words.

Gazi's knowledge and asks questions related to Sufi mysticism. Gazi answers satisfactorily and at one stage Kalu points out the asha of the Gazi. [The asha is one of the most holy ritual accessories that play an important role in the performance of the miracles of the saints (Pirs). It indicates the symbolic representation of a saint's supernatural power. During the Gazir Gaan performance, the asha is implanted in the ground and is not used in the performance. Other ritual accessories are used in Gazir Gaan and the offerings made to the saints in the performance are usually taken by the lead-narrator or singer himself on behalf of the saint.

At the end of the performance of each episode of the Gazir Gaan, the narrator asks the crowd which episode would they like to watch. The troupe performs accordingly because it is the mood of the crowd that matters to really feel the beat of the performance. (Saymon Zakaria, August 30, 2004) .Among the indigenous Bangalee art forms, pata-chitra or scroll paintings stand apart in their choice of subjects, vibrant colours, unique lines and style of presentation. Painters of this form are called patua. An exhibition of traditional pata-chitra by three patuas, Dukhushyam (Osman) Chitrakar, Rabbani Chitrakar and Rahim Chitrakar, is being held at DOTS Contemporary Arts Centre on Tejgaon-Gulshan Link Road. (Daily Star, April 9, 2006).

The term Pata is derived from the Sanskrit word Patto, meaning cloth. In ancient times, before paper was introduced, artistes used to paint on thick cotton fabric. Usually mythical or religious stories were the themes. However, in time contemporary issues, animals and more found their place on these painting. "Pata-chitra is perhaps the oldest art form in the Indian subcontinent and the tradition continues to this date. In fact, the art form can be traced all the way back to sixth BCE."

Besides being visual delights, the scroll paintings are also used in pat gaan or patua gaan. Through the medium of scroll painting, a choir narrates a story. Most of the paintings in the exhibition illustrate myths, episodes from the Purana, Ramayana; some feature animals and imaginary monsters. The paintings have several sections so as to maintain a sequence. In the first segment the main characters, usually Gods and Goddesses, are portrayed boldly. A painting featuring Raashleela of Radha-Krishna is stunning. Snake-like creatures with three heads on another one are interesting. Another painting shows three gruesome rakhkhoshi (females monsters) in their "full glory" -- teeth shaped like carrots sticking out, talons sharper than an eagle's -- staring back at the viewer as if to warn them to keep a safe distance.

Goddess Durga is the subject of several scrolls. One of the paintings show the Goddess smiting the beast Mahishashur. Vibrant colours -- yellow, indigo, bottle green, khaki, crimson and dark brown -- create a dazzling effect. Four Gods and Goddessess -- Ganesh, Karthik, Lakshmi and Saraswati -- ornate the corners of the painting. The story of Goddess Kali stamping on God Shiva is the subject on a scroll. The Goddess is bare, as she is portrayed traditionally and painted in deep purple. In episodes from the Ramayana, Rama and Sita are seen getting married in the first segment. Other scenes featured are Lakshman cutting the nose of the monster, Suparnekha and Sita abducted and imprisoned by Ravana. An interesting scroll shows fish carrying other fish in paalkis.Bangladesh is home to long and rich folk tradition. Dr. D. P. Ghosh (1980) says, "two thousand and five hundred years ago, scroll painting or panel painting was widely used in this country." The art of Bangladesh influenced the art of the Far-East, especially the art of Java. In Bangladesh, folk painting is a part of vast folk culture, developed from time immemorial (Prof. R. Alam,2001).

The patuas are artisans, who are now principally engaged in decorating pottery which is also a dying craft. Now a days we do not find any Patua in one time famous Patua colonies of Bengal.

In Bengali Chal Chitra (inverted shaped roof like design) are employed on the clay images. Chal Chitra are done by the village folk artists. This has become a dying art.

Ghat means water pitcher in Bangla. Manasa is the snake goddess. These ghats are made from clay on the potter's whell and then dried and burnt. All the Ghatsare absolutely folk in nature and primary colours are bold draughtsmanship are employed. The style of painting has affinity with ancient Egyptian and Minoan painting, especially in the depiction of eyes.

Vratras or fasts are innumerable folk expression by women.In Bangladesh a number of Vartas undertaken by Hindu women necessitate the making of clay images as well as Alpana (Folk art - a spontaneous expression of the people, retains the past experience of the community and yet also a vital existence in the present... Flowering of the women's creativity marks each changing cycle of the year. Alpana designs were originally used to be drawn by spreading white powdered rice or by drawing lines on a layer of this powder, A. Mookerjee, 1939)). some scholars hold that Alpanas have come down to us from Austric people (such as Mundas).The rural Bangladesh has a thriving tradition of making dolls and toys from different indigenous materials. Two specimen collected by BSIC, Dhaka - head of a tiger and head of an elephant. The form was made from clay which is covered with the pulp of paper and then painted. One interesting relict has been discovered at Commila. It is a design done over a terra cotta . This unique piece has a design which is folk in character (R. Alam,2001).

Sara or cover is an earthen plate made of clay which is burnt. Generally Laksmi the goddess of wealth is depicted on the Sara. Sometimes Durga, sarasswati, mansa and other deities are also painted. These Saras are generally painted by the men of the potter cast assisted by women folk.

WOMEN'S CULTURE

5. Glorious Heritage is going to Perish

Our glorious heritage is going to perish. But with the loss of traditional culture, we are going to lose the values of our life that our ancestors preserved.

Recently in an editorial the daily Independent writes:

"Reports coming from different parts of the country narrate the decline of pottery as an industry and plight of potters who have for generations subsisted on their trade. An agency report from Sherpur published in the Country Page of The Independent yesterday says referring to a study that the pottery of that place which was famous throughout undivided Bengal is now becoming extinct. The traditional potters are switching to other professions."

Pottery Gasping For Breath

Faridpur, Feb. 18: Pottery in the district is grasping for breath throwing a large number of potters into total uncertainty. It is learnt that the demand for pottery has decreased due to availability of silver and plastic materials at reasonable prices. People in general prefer plastic or silver articles to earthen pot considering their durability and decency. A potter told this correspondent that a day labourer can earn Tk 70 to Tk 80 (Tk. 50 = one US Dollar) but it is difficult to earn Tk 80 a day by selling earthen materials.6. Health Hazrads from Modern Household Articles

Use of plastic bottles can cause cancer

A research on repeated use of plastic bottles conducted by Australia based Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Mines Staff said many users are unaware of poisoning caused by reuse of plastic bottles.

Experts have said that repeated use of plastic bottles of mineral water might cause serious diseases including cancer to the users, reports BSS (January 21, 2004). The findings recently circulated in the UN bodies locally said that some users might be in the habit of using and reusing disposable mineral water bottles and keeping them in the cars or at work. The researchers suggested that it was not good idea to use plastic bottles more than once as the plastic called polyethylene terphthalalate or PET used in these bottles contain potential carcinogenic element, a cancer causing chemical agent.

Repeated washing and rinsing could case the plastic to break down and the carcinogens can leach into the water that the users are drinking. It is better to invest in water bottles that are really meant for multiple uses . The experts cautioned that the children should especially be protected from the repeated use of disposable plastic bottles as it could harm their health very easily.

Bangladesh's water is aluminium rich and most people in villages does not cook on clay pots but aluminium pots. Hot spices, vigrous stiiring and arsenic removal by aluminium sulphate are adding additional aluminium:

ALUMINIUM & BPA POISONING - AN ADDED ANXIETY

The concentration on " chemical treatment at household level" as a solution for arsenic in the groundwater has resulted in an increase in the use of aluminium sulphate. Yet this could be a cause of aluminium poisoning. As, according to the experts, a person who already has arsenic related diseases will have a greater manifestation of arsenic poisoning, this should be of concern.

In other words if treatment to remove arsenic from the water is done at home, the risk of aluminium intoxication is vastly increased as the floc ( aluminium hydroxide) that separates out when the sulphate is mixed with water is amphoteric- i.e., it dissolves in both alkaline and acidic solutions. When aluminium sulphate mixes with water it release both aluminium hydroxide solid AND sulphuric acid. If too much aluminium sulphate is added, the acidity, due to the sulphuric acid, becomes so high that the hydroxide re dissolves. This gives a clear and apparently pure looking solution which people think is safe to drink.

Since so many people are already vulnerable to arsenic poisoning as well as iodine deficiency, it is totally unacceptable to discount exposure to a known neurotoxin-and one with such devastating results - on people already under severe environmental challenge. Exposure to environmental aluminium is one of the great disasters of our time and one which will eventually become much more widely accepted as the evidence continues to accumulate. And since lemons are used so extensively in Bangladesh in cooking, you get primary attack on the aluminium pots by the acidity of the lemon, then the formation of an aluminium citric acid chelate, These chelates are one of the most dangerous routes of infiltration into the body for aluminium , and wherever special circumstances, such as this arise, it is highly dangerous to use aluminium for cooking utensils. (Doug Cross-Environment Consultant).

A recent study by Koji Arizono and other researchers at the Prefectural University of Kumamoto and the University of Nagasaki, Japan shows that bisphenol-A (BPA) in plastic tableware and other utensils leached into hot liquid. Worn or scratched products leached even greater amounts of the chemical. Low doses of bisphenol-A(BPA) have been found to cause reproductive malformations in male rat off-spring, including deformed genitals and enlarged prostates. With new research indicating that plastic feeding bottles and utensils in common use could have serious consequences for human life, this is of concern as plastic buckets are in use in the treatment of arsenic contaminated water. BPA leaches out of plastic even at temperatures as low as 60 degrees Celsius therefore the use of plastic buckets for treating arsenic-contaminated groundwater could therefore be dangerous without the addition of aluminum sulphate to the water.7. Pottery Faces Extinction

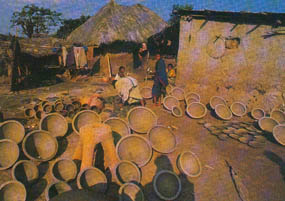

Our project advises villagers to use traditional clay pots to escape health hazards and to keep the money in the villages.

Preserve tradition of pottery from extinction

From the very beginning of our Banglee culture, pottery has represented our identity and lifestyle. The artisans' works include making clay-pots, earthen ware, toys of clay and different idols of gods and goddesses have been the tradition of our culture. But it is now regrettable that in recent times, especially in the last decade potters have been in distress. Because of these unavoidable factors like clay, lack of capital, unsatisfactory selling of clay pots, lack of fuel wood for burning raw pots, their plight is in peril.

Earthenware and fashionable things of clay are being rapidly supplanted by aluminum, plastic, steel and other alternative materials. Even toys for children are being made with wood and cloth. Besides, so cold prestigious people never tend to buy earthenware thinking their image and status. But it is admitted everywhere that cooking pot of clay is more conducive to health than pot of silver or other materials. Cooking rice of clay-pots help to cure gastric problem. And pitchers keep water cool in hot days. Another cause for not selling clayware is its brittleness. Inspite of being more cheaper than other aluminum or plastic made pots, clay-pots are not being sold available. Thus potters have to survive with a negligible earning.

To observe the present condition of potters I visited Vaagandanga village in Faridpur, my home district on spot. A potter named Paras Chandra Pal told with rage, after liberation war many potter families had left the country away. The reason behind their leaving home allegedly are precarious future of pottery, oppression by neighbours as communal violence, political molestation & feeling of dire insecurity. He also informed that to bring money as a loan for capital from banks, they have to pay bribe to bank officials. NGOs often help them by providing loan with low interest. Potters are also concerned at the rising price of fuel wood and clay. Above all, their hard labour to pottery is not undeniable at all. Many of them grudgingly rush to adopt another occupations leveing pottery gradually.

Hence, government and connoisseur of pottery both should come forward to alleviate their poverty and evaluate their artistical work precisely. The commoner can also play a role merely considering the question of precisely. The commoner can also play a role merely considering the question of preservation of our Banglee tradition.

(Source: Palash Podder, Dept. of Socilogy, Dhaka University, 27 August 2003)

Pottery faces extinction in Moulvibazar, SylehtSept 28, 2003 : The traditional pottery industry in the district is on the verge of extinction. Hundreds of potters have been thrown into uncertainty. Many potters have already quit their ancestral profession being unable to cope with the problems engulfing the age-old industry.

According to knowledgeable sources, high prices of necessary raw materials like kilts clays, dice, dye, fuel and dearth of capital have affected the industry adversely. Besides, the demand for pottery products has fallen in the local markets due to availability of stainless steel and aluminum products to a considerable extent. With the passage of time it is apprehend that the artisan community will have no other alternative but to adopt other jobs for their survival. On the other hand, the number of unemployed people has escalated rapidly in the district due to large-scale erosion and recurrent natural calamities

Rajnagar, Kulaura, Kamalganj and Sadar upazilas have been affected by erosion by the rivers Monu and Dholy that has already rendered many farmers into day-labourers, rickshaw-pullers and even beggars. Their arable lands have been washed away by the mighty rivers. In many cases the farmers are compelled to sell their property due to the burden of standing agricultural loan. Consequently, these frustrated unemployed persons are committing crimes in different areas.

Source,Staff Reporter, The Independent, September 29, 2003)

Pottery faces extinction in Nilphamari

Pottery industry is facing extinction in Nilphamari district in recent years. It is gathered that a large number of people connected with this age-old profession are passing their days and nights in extreme poverty. About 20 years ago, different kinds of utensils and other household articles used to be made from clay by the potters in all the six upazilas of the district. The artisans used to make different kinds of utensils, glass, plate, pan, doll, ladle, bowl, spoon, tray, pitcher, jug and toy with special kind of clay.

At present, the potters are not earning the minimum income to survive with their family members. Those glorious days of their profession are no more. With the advancement of modern technology, the idyllic days are gone. The potters are systematically marginalised due to the stiff competition. The pottery industry is literally gasping for breath.

The upazila-wise break-up of the potters were as follows : Some 3,070 people were involved in pottery in Domar upazila, 3,160 in Dimla upazila, 3,220 in Jaldhaka upazila, 3,340 in Kishoreganj upazila, 3,000 in Saidpur upazila and 5,710 people were involved in the pottery industry in Sadar upazila. But till now about 80 percent of them left their ancestral profession as they failed to earn money for their bare necessities of life. Only a negligible number of people are now sticking to the profession with much hardship in the district.

This correspondent talked to some people connected with pottery in Domar, Dimla and Saidpur upazilas and came to know that due to the increasing pressure of the modern household utensils and other articles they have compelled to quit their ancestral profession. They added that the remaining people would also quit the profession in the near future if the present trend continues. They said that the government should patronise the industry for its survival (The Independent, December 19, 2004).

Pottery units struggle for survival

Nov 10, 2004 : The traditional pottery industry all over the district is on the verge of extinction, throwing hundreds of potters in utter helplessness. Meanwhile, a large number of potters have already quit their ancestral profession being unable to cope with the problems engulfing the age-old industry.

Besides, the demand for pottery products has decreased in the local market due to easy availability of stainless steel products in the markets to a considerable extent. With the passage of time it is apprehended that the artisan community of the district will have no other alternative but to adopt other manual jobs for their survival (The Independent, November 11, 2004).

Sumon Bepari's endeavour to save the pottery craft

The concept of interior designing is changing rapidly all over the world. At the same time, interest in using local raw materials for decoration is increasing amongst our designers. They are trying to give our tradition of handicrafts an access from drawing room to kitchen. This change is bringing back the terra cotta which is on the verge of extinction at present. Now our pottery industry is making room for itself besides the exotic showpieces. With the ambition to conserve the pottery, Sumon Bepari holds his second solo exhibition at the Drik Gallery.

Sumon wants to bring back the lost glory of the colourful earthen pots. That is why he applies his creativity on earthen vessels more than the canvas. 'I know that this media of art is very temporary but to save this industry we should take initiatives to face the challenge of modern times.'

He has wandered about in our rural areas, with his camera, to learn more about the potters' lives. At that time he tried to frame the nature as well as rural lives in his camera. Some of his photographic excellence is also on display. Sumon says everything is done here for love of his motherland.

(Source:Kausar Islam Ayon, The Daily Star, October 7, 2003).Potters' wheels keep spinning in Bamunkushia

"Good days are back again," sings Indranath Pal with a happy giggle, standing in front of a row of tin-sheds owned by potters in his village that is a sure sign of rural prosperity. Prosperity has erased frustrating stagnancy for potters like Indra, a middle-aged member of the pal community in Bamunkushia village, four kilometres east of Tangail town."The change you see now began only five years ago," explains Indra, who pioneered the change. Thanks to a rise in the installation and use of sanitary latrines by the government and NGOs (non-governmental organisations), Indra and his fellow potters in the village reinvigorated their occupation by linking up with the sanitary product boom. When he first saw the ring slabs of the sanitary latrines to be put in sanitary wells, it occurred to Indra that potters could make ring slabs with clay instead of cement.

Pursuing the idea, he found the cost of clay slabs would be less than those of cement. His next step was to campaign in the neighbourhood to attract buyers. His campaign yielded the expected result and customers gradually began to put in orders. Once there was a steady flow of orders, other potters joined in. Chhidam Pal, Anil Pal, Lalchan Pal, Jogesh Pal, Gouranga Pal and Govinda Pal -- all started making ring slabs as well as flower tubs and small pots for seedlings.

"Some families have migrated to India. Some changed their profession. Ten years ago, I also thought of becoming a rickshawpuller. But eventually I couldn't leave my ancestors' occupation like many of my community. We are artisans. Art is in our blood. It's not so easy to leave it," Indra remembered the hard days for his community before the new work became available.

The people in this ancient occupation have been having a hard time for years. The demand for clay utensils has diminished over time due to the availability of cheap, handy alternatives, made of aluminium or glass or plastic. The trade has also been hurt by the migration to India of many of the Hindu community.

In such a context, the success story of Bamunkushia stands as an exception. Making ring slabs is not really new for the potters. "We used to make the same things for the dug wells which are no more in use," Indra said. "This is only a new use of the old things."

Potters from Basakhanpur, Inatpur and Taratia villages are also making clay slabs now. More orders keep coming in. Seventy-year-old Chhidam Pal, one of the senior potters in Bamunkushia, happily observed the tin-shed: "We have done it with our own merit and labour."

"But getting fuel to burn the clay is a real problem nowadays. Nor are there as many boats today to carry the load of mud, as you found before. Not many boats now sail long distances," Chhidam said. Siddhipal, another potter, emphasised the need to increase their sales. "We don't require NGO or government loans. We only need proper arrangements to sell our products. Bigger markets."

But Indra is full of hope for the future. Last year, he made a dug well in Bidyut Saha's house at Kalihati in Tangail. It was a Tk 5,000 contract. "The well was dug to get arsenic-free water. I hope many more will call us to dig wells. People are returning to older days. Our pottery will surely have a comeback." (Daily Star, January 17, 2004)

8. Balcksmiths Face Extinction

A large number of blacksmiths oof the country have been facing manifold problems for a long time. Price-hike of raw materials, lack of patronage by the relevant authorities and shortage of fuel are some of the problems the blacksmith community has been confronted with.

Some blacksmiths told this correspondent recently that they were not getting fair prices for the tools made by them despite hard labour. Very often they are compelled to sell their goods below the production cost to maintain their families. They added that the demand for their products has fallen due to easy availability of machine made tools. Subol Chandra, 36, son of Rabi Chandra of village Chandaikona in the district, told this correspondent that he had no scope to expand his business due to dearth of capital. Banks do not provide loans to them. So they are totally dependent on the moneylenders. But they cannot borrow money from them due to high rate of interest.

Once upon a time there were about 30,000 blacksmith families in the (north Bangladesh) region covering 16 districts, but now their number has come down to 2,000 only. Most of the blacksmiths quit their age-old ancestral profession and switched over to other jobs for survival.

But in the absence of suitable jobs they are leading sub-human life with their families. They make knives, billhooks, spades and axes. Their skill makes our lives easy because without these tools we cannot spend a single day in the city or in any village. They are blacksmiths otherwise known as Karmakars or Kamars as several of these communities live in the city. At Karwan Bazar around 250 blacksmiths work in 25 workshops. The air filled with the odour of smelting iron in manually regulated foundries, harsh sounds of the anvil on the hot iron as it flares and sparks characterises the area. They working environment is risky; hazardous to their health. They find difficulty in breathing because of the lack of oxygen in the air. They inhale iron dust, which, according to doctors is a cause for cardiac disorders. To run the profession smoothly, the blacksmiths need crude iron, steel, gas pipes, charcoal and other raw materials, but prices of these materials have been increasing from time to time. A kilogram of charcoal is selling at Tk 25 to Tk 30 in different markets

Blacksmiths make tools like spade, axe, hoe, rake, plough, sickle, knife and other household materials. But the demand for these tools has fallen remarkably in recent times. They have urged the authorities concerned to provide them with short-term loans to help continue their ancestral business (The Independent, October 15, 2004).

Blacksmiths now in peril, seek technological, easy loan facilities

BHAIRAB, Feb 22, 2005:—Blacksmiths in the haor area of Itna, Mitamoin, Nikli and Austagram upazilas of Kishoreganj are passing hard days as they can not produce iron made products for marketing due to price hike of necessary inputs and capital shortage. The blacksmith community of the upazilas living on their ancestral houses are producing and selling iron made products like dao, axe, spade, sickle, knife, kitchen knife, pins, agricultural inputs and other items essentials for daily use. But the unusual rise in the price of raw materials mainly iron has pushed them into extreme difficulties to maintain their traditional profession. In the wake of the price hike of iron they cannot manage capital to run their pursuits.

Besides, the demand of indigenous products is on decrease due to availability of quality imported products comparatively low price. Some blacksmiths have left their ancestral profession and leading miserable life with their dependents. The blacksmith community should be provided with improved technological support and easy loan facilities to run the ancestral profession (The Bangladesh Observer, February 23, 2005)

Blacksmith industry grapples with problem

About 2,000 blacksmiths in the under the district are facing great hardship for a l ong time. Lack of patronzation, hike of raw materials, crisis of fuel and charcoal and, for the setting of welding workshops, the blacksmiths find it difficult in carryout their ancestral profession. Besides they do not get fair price of their products due to lack of marketing facilities. They are forced to sell their goods at a nominal price. According to different sources there were more than six thousand blacksmith families in the district. But now the number has come down to about 2,000. Many of the blacksmith community have already quit the profession and changed their professions for the cause of survival and many of the are thinking to quit finding no other alternative. Talking to a blacksmith Anil Chandra Kamaker at village under Sadar upazila it is learnt that they have inherited the age old profession. Now they are passing their days in extreme hardship due to want of capital fuel and raw materials. hey need steel and iron as raw materials. But the prices of raw materials have increased manifold and informed they need fuel for heating the steel and iron to make various agricultural instruments. Kitchen , carpentry instrunents and joining tools used in furmiture making. They usualy use kath-koila (charcoal) for hearing raw materials. They used to purchase charcoal at Taka one per kg a few years ago. Now they purchase it at the rate of firewood, he added.

But the supply of coal is not available at all. So they have to look for charcoal in the rural areas. According to reports supply of spade hoe, rack plough blade, sickle billhook knife chisel hammer house and furniture making pin hinges ring etc. made of steel and iron have reduced largely. Non availabilty of raw materials has hampered in making of those ones.

A good quality of steel is necessary for making sharp iron stoll like , plough blade, cutter etc. According to sources market position of the iron made articles has quite changed after introduction of mechanized cultivation, Talking to some blacksmiths in the district town it was learnt that the demand of plough blade locally known as Langaler Fala is decreasing day by day due to use of power tiller largely. Now a-days ready made modernized tools for house hold works and cultivation purposes are selling in the markets at a cheaper . With a view to present and market prices of raw materials the artisans can not make profit as their cost of production is exceeding the selling rate Nipa Karmaker in age old blacksmith industry nBazar in Sadullapu upazila told this correspondent that traditional blacksmith industry is almost closed down due to want of fund. They need a large amount of money to purchase steel and iron. But they are not in a position to draw loan from banks as they do not have sufficient fund to mortgage to banks. As a result they are mainly depending on the money. This profession is of more gainful that is why many of them have meanwhile left the profession and are living in sub-human condition. The blacksmith community of the district appealed to the commercial bank authorities to districts to grant loan among them at easy terms for the survival of the age old cottage industry (The Bangladesh observer, June 20, 2007).9. Traditional Jewellers on the Wane

Subodh Karmakar, 38, works in his small outlet, Sananda Jewellers at Khorompotti in Sherpur. Two other young boys help him. As winter is considered the marriage season, he is rather busy. This year, unlike previous ones, his business is very dull and few orders are coming in. Subodh has been involved in this profession for over 23 years while his family for generations, but most of his family members have changed their profession. He opened Sananda Jewellers independently in mid-June in 2003. Before that he had been working at Muslim Jewellers in the town. "As I don't have education, I have no choice but to get involved in this profession," says Subodh.

According to him, people of the traditional jewellery-making families no longer get encouragement from their guardians to be involved in the profession because it has lost both its novelty and the wealth. Only youngsters, who do not have education and do not get the chance to be employed elsewhere, take to this line of work. Every year, many workers, who are involved in this kind of profession, are changing their occupation. "Many workers have become rickshaw-pullers or farmers. The people, who are new in this profession, do not have much of a reason to keep at it." Subodh said. Jewellers are no longer getting orders to make traditional hansuli, boyla, kantabaju, bangaguli, bank kharu, moti chur, basanta bahar churi, chakra har, sat nari, machhipat, elokeshi ring. "The prices of these items are very high; we cannot afford them." said Momena Nahar, a young housewife who had come to buy a makori and kanphol.

Almost all the owners of small outlets take orders from big shops like Subodh, who takes his orders from the Muslim Jewellers, where he used to work. He feels that the situation has worsened due to the price hike of raw materials. Like the other parganas in Bengal, different areas of Sherpur were ruled by zamindars from the Sultani period. During the British rule, there were some 15 zamindars in this region. The jewellery industry had spread widely in these areas at that time.

According to goldsmiths, the degradation in this profession, in fact, started in the 1960s. After independence, the situation became even worse. The people of Basak, Malakar and Karmakar families, who were famous for their traditional jewellery works, are now changing their profession.

This traditional business is now facing tough competition. Many of the shops are buying substandard readymade jewelleries from Dhaka and selling those here because of which costumers are losing faith in the producers. Suresh Malakarer Dokan, the oldest jewellery shop in town, has been there for eighty years. The proprietorship has been passed down the family for the past seven or eight generations. About the present condition of this profession one of the proprietors, requesting anonymity, said that the goldsmiths were not surviving, as they were not adopting the modem technologies and new fashions. According to him, lack of capital, non-cooperation from financial institutions, lack of any government and non-government assistance are the main causes for the slump in this industry.

"The smiths cannot afford new machines. So they cannot introduce new designs. The light and poor quality products as well as the high price of raw materials have also took the industry to the verse of destruction," he comments. Over the years, certain areas in Sherpur have become specialised in jewellery and known as Sonaprara. Most of these villages have now lost their fame.

They said that the industry in Nabinagar Sonapara has faded away. "Some of the families of Pakuria Sonapara, another locality near Nabinagar Sonapara, have had the tradition for many generations. This indicates that this industry had flourished here many years ago.

The goldsmiths of the town think that the jewellery industry is improving and flourishing day by day in India. Both government and non-government organisations are assisting this small industry and guiding the owners of the jewellery shops as to how to better their sales. They are earning huge amounts of foreign exchange, exporting jewelleries. But in Bangladesh the scenario is pretty much the opposite. When asked about the loan distributing programmes, the authorities concerned at Sonali Bank and Janata Bank in town informed this correspondent that they do not have any special plans to distribute loans to revive the cottage industry. They also said that many of the jewellery shop owners had come to take loans for other purposes. There are about 300 shops, including 100 showrooms, throughout the district.

Many of those employed here are loosing their jobs. "Those who loose their jobs find employment in different sorts of job. Those, who do not get new jobs, are setting up new outlets in their own areas so that they can also do their domestic household works." said Abdur Rashid Majid, Joint Secretary of the Bangladesh Jewellers' Samity in Sherpur (R. Rosan, October 22, 2004).(

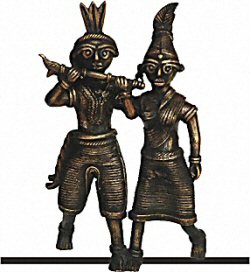

The Lost Art of Metal Casting

10.The Lost Art of Metal Casting

The lost-wax technique is an ancient art that dates back over 2,000 years or older in India, China, and Egypt. In the 15th century it was used by the likes of Donatello for the making large-scale bronze nudes. Bowls and plates made with intricate etchings are made using other methods.

Process

Material

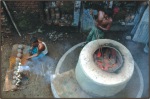

First, the artisan creates a sculpture using wax made from beeswax and paraffin. Three different compositions of river-based clay are then poured over it, two times each. Two nali or openings are molded at one end of each piece. Thirty-six to forty crucibles of brass and bronze metal are arranged at the bottom of a five-foot cylindrical brick oven. Placed over these are the clay molds containing the wax figures. The cylindrical oven is so deep that one of the workmen must go into the oven to lay the raw clay structures. When the crucibles and molds are in place, the oven is fired up. A great mass of smoke rises from the open-top oven, taking the form of a miniature Hiroshima explosion. A 20-foot high flame created by the burning wax discharging from the clay molds eventually replaces the smoke. At this point, the oven has heated between 175-200o centigrade. In the end, none of the wax will remain leaving behind hollow molds. From here arises the term "lost wax". Two and a half-hours after firing up of the oven, the metal starts melting at a scorching 1000o centigrade. Once the metal is liquidified, the scalding hot clay molds are removed from the oven using six-foot long tongs. The empty molds are turned over to expose the nalis and the red-hot molten metal is poured in. After the metal cools down and takes solid form, the outer clay of each mold is chiseled away to reveal a silvery brass statue, a replica of the original wax sculpture. The figure is filed and polished. Lastly, chemicals are added to its surface to give the metal its characteristic patina. The statues are fit for display. Most of the figures are made from bronze (a copper and tin alloy) or brass (a copper and zinc alloy). Hindu figures are made out of eight metals believed to have an auspicious connection to the planets. The eight metals are: copper, zinc, tin, iron, lead, mercury, gold and silver.

The Wax Artisan

Once a dying art, metal-casting is being revived by Sukanta Banik, whose business in Dhamrai has been in the family for five generations. Until recently, Banik's forefathers had been making household items with brass and bronze -- kasha and pittal. But in 1971, Sukanta's uncle Shakhi Gopal Banik and his partner, Mosharraf Hossein, changed direction and started producing works of art: figures from Hindu mythology and folk art as well as Buddhist and Jain sculptures.

During Durga Puja season most of the artisans go home to work on clay murtis for their family business. "Wax figures are harder to work on than clay ones because we do replicas of museum designs, but clay murtis are our own creation," says Gautam Pal, the sole remaining artisan of the season.

Designs of the gods and goddesses

Designs of the gods and goddesses are based on the art of the Pala dynasty. They tend to be very intricate, and stand distinguished from statues made elsewhere,

The lost-wax technique allows helps Banik's artisans create more pronounced detailing. In contrast to most Indian statues, whose details are etched onto the solid metal form, the details of one of Banik's statues are made on the soft wax at the initial stages of the sculpting, using soft wax thread, which is then carved into with a bamboo stick. Thus, the embellishments take on a three-dimensional quality.

Murtis from India also differ in that they are usually made from a Master mold.We must attempt to preserve this age-old tradition, not just in Dhamrai, but in other centers like Jamalpur, Islampur, Tangail, Kushtia, and Dhaka." In the words of friend and supporter, Matt Friedman, "If [the metal casting] trade is someday lost, an important part of Bangladesh's artistic tradition will vanish forever." Hats off to Mr. Banik for bringing this decidedly Bangalee tradition back to life (Manisha Gangopadhyay, November 8, 2004).

11. Satranji : Weaving for a cause -Rugs steeped in history

Even if it's not Aladdin's magic carpet, the lure of the 1,000 year old traditional jute rug --Satranji continues to have buyers in its thrall. The elegance and splendour of the rug is believed to have captivated even the great Mughal Emperor Akbar. The charm of Satranji was evident both in palaces and huts. Recently, the lyrical beauty of the Satranji was on display at the lounge of the Pan Pacific Sonargaon Hotel. Hanging on walls, placed on a traditional Palanko( the highly decorative antique bed of kings, nawabs and zamindars), the soft lighting created a dreamy atmosphere with splashes of bright colours at the exhibition premises.

With the title 'Colour Your Home with Village Art', a three-day exhibition started on October 3, 2004. The organiser was famous designer Bibi Russell in collaboration with Pan Pacific Sonargaon Hotel. The exhibition is a fund raiser.' Twenty percent of the proceeds will be donated to Lifebuoy Friendship Hospital. The rest of the funds will go to the North Bengal weaver community who made these magnificent rugs,' said Bibi. 'We are focusing on the women weavers of Rangpur. They have suffered a series of natural adversities- the harmful flood, devastating rains and drought. Consequently, these people are uncertain about how to celebrate Eid.

In the exhibition, around 80 Satranjis made of 100 percent jute, are on display with various colours and designs in folk tradition. From Pilpa, which was known as Hatipaya to Jafri, Itkhati, Latai the traditional mingled with modern designs depicting the motifs of elephant footprints, motifs from Jamdani and the intrinsic geometrical patterns. About the designs Bibi says, ' The traditional motifs are absolutely superb (Afsar Ahmed, Daily Star, November 5, 2004).

Shatranji: An old heritage

Shatranji, a variety of handloom carpet which is the heritage of Rangpur and the country, has had a chequered history. Once exported from Bangladesh to India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka it had earned acclaim for its extraordinary aesthetic appeal. Though Shatranji was produced profusely in the village of Nishbetganj (earlier named Parbotipur), technological advancement and colonial aggression led the craft to the verge of extinction. In a precarious situation, the weavers began to look for alternative sources of income.

Going back in time, the history of Rangpur has it that Shatranji of Nishbetganj was greatly popular in the Mughal period. In fact, it is believed that emperor Akbar used this Shatranji to adorn his palace in Delhi. Over the course of years, the cottage industries of Shatranji have been set up in Pakistan, Iran and India, using the techniques of the Nishbetganj. These countries have kept their industries running profitably and have also ventured into the export market. Another promoter of the craft is a Swedish organisation, which came to Nishbetganj with funds to revive the cottage industry. The organisation provided the weavers with money and purchased Shatranji in return to send to Sweden. However, a while later the organisation withdrew its support, leaving the weavers high and dry and spelling the end of the project. Fortunately, help was at hand. An entrepreneur Shafiqul Alam Selim came forward with a creative plan to re-establish the cottage industries of Shatranji at Nishbetganj.

Gradually, Shatranji earned renown with new designs and weaving techniques.Today there are over 300 Shatranji weavers. Shafiqul is highly optimistic about the future of this cottage industry. "I am an optimist and believe that talent and sincerity can lead to success. It is a measure of success that Shatranji has crossed the country border and is being exported to foreign countriesalbeit on a small scale.12.Bamboo-based cottage industry faces extinction

Bamboo-based cottage industry in Shariatpur, Madaripur, Gopalganj, Rajbari and Faridpur is on the verge of extinction due to lack of raw materials and shrinking of market for the products. Market sources said the short fall in raw materials is triggered by indiscriminate extraction of bamboo trees for building houses and various goods, uprooting the bamboo for setting up settlements and lack of any initiatives to preserve or grow bamboo clusters.

Besides, the local markets are being flooded with metal or plastic goods leaving no rooms for the bamboo made ones. Consumers are increasingly buying metal or plastic goods instead of bamboo-made products because of their cost effectiveness and durability. As a result, thousands of bamboo craftsmen have already left their inherited profession in search of alternative jobs. A large number of them have become jobless finding no other alternatives, the sources said.

Bamboo the life blood of the people: Alarm to Ecosystem

Talking to BSS people involved in the bamboo industries said the government should take programmes to plant bamboos in the areas to help the craftsmen for survival in the competitive market. They also stressed banning on carrying indiscriminate extraction of the bamboos from the areas (Independent, December 12, 2004)..

13. The fading trade and the fading away shankharis

Uttam Naag, one of the oldest and most gifted shankharis (shankha craftsman) in the city's Shankharibazar area, showed the door to this reporter when approached for an interview. “If I give you an interview will it bring food for me? I have done it many times in the past 10 years. Many reporters talked to me. Stories were printed. But none of it changed my life. It has become quite tiresome for me,” said a frustrated Uttam.

It was midday but inside his 3X10 feet workplace it seemed like evening despite a single low-power electric bulb giving feeble light. There is hardly any space for one person to move freely. Dust of the conch shell made the room suffocating. Uttam and his five colleagues work in this room in such a harsh condition.

Once part of Dhaka's rich history, the art of shanka (conch shell bangles) and the craftsmen are now just awaiting extinction. “There was a time when every household of Shankharibazar area was involved in shankha trade one way or the other. Shankha used to be the identity of this area. Today it exists only in name,” said Uttam who has been involved in this trade for the last 40 years.

Only a handful of craftsmen now remain in the profession. According to Shankharibazar Shankha Shilpa Karigar Samity, at present only 25 designers work in four workshops and another four work at their home. Only eight are engaged in shankha cutting in the samity's automated factory.

There are many problems and intricacies behind the depressing state of the age-old trade and the tradition, shankharis and the shankha traders pointed out. The first blow came during the Liberation War. Shankaribazar, which has been the home of shankha trade for several hundred years, faced the wrath of the Pakistan Army in 1971.

The shankhari community saw a massacre along with their rich heritage. Besides, many artisans migrated to India during and after independence.

Artisans attributed the influx of cheap Indian shankhas to the dying shankha trade and blamed the mahajons for destroying their livelihood. “Indian products have taken over the local market taking away the business of Shankharibazar's craftsmen forcing them into starvation,” said Uttam. “Influx of Indian products means fewer work orders, reduced earning and changing of profession for us.”

He mentioned that charge of the craftsmen depends on the intricacy of the design and the amount of time it requires. The usual rate ranges from Tk 6 to Tk 20 per shankha. The workers' daily income varies, but generally it ranges between Tk 150 and Tk 300. The shankharis abandoned the age-old manual saw and started using electric saws around 20 years ago. It increased the production and reduced time of their work.

Shankharibazar Shankha Shilpa Karigar Samity possesses the only factory that employs automated cutting machine. The entire community in the area uses the machine. “Hindu women use to wear shankha for religious reason. Today's modern women wear it also as a fashion statement. So it has tremendous business opportunity. But for the lack of patronage the trade is dying,” said Madhushudan Dhar, a cutting labourer.

Mahajons on the other said supply shortage of raw materials and high import duty is the main reason why local shankha industry is facing a depression. “The basic problem with the trade is that the raw material, the conch shell, has to be imported, as it is not available in Bangladesh. Majority of the supply comes from Sri Lanka,” said Mithun Naag, owner of Naag Bhandar.

The quality of raw material is deteriorating but its price is rising. In addition to this, there is very high import duty. As a result, the local products get costlier, he said. Price of a good piece of locally made shankha starts from Tk 600 and it can go up to Tk 1,200, whereas Indian shankhas cost between Tk 150 and Tk 500.

The import duty on conch shells is currently 35 percent and it takes about three months to receive the shipment from Sri Lanka as it has to come via Singapore. On the other hand, the Indian conch shell traders pay only 5 percent duty, which makes their product cheaper. Another problem with the shankha industry is that it involves a very small community and they live in a particular area. There is little opportunity to expand this industry as only the shankhari community is involved in this craftsmanship for generations. With current pay new apprentices are hard to find, Mithun noted.The Hindu myth of shankha bangles

In Hindu religion it is mandatory for married women to wear shankha bangles. By wearing shankha a Hindu woman seeks well-being of her husband. It is considered as a symbol of her purity. Shankha is also an expression of love and devotion to the husband. It is believed that shankhas protect women from bad omen. Use of broken shankha is considered ominous.

These bangles come with magnificent carvings. Carving out these bangles from a hard conch shell is like making a sculpture out of stones. Making a shankha needs time. First the softer part of the shell is taken out by breaking the tail end of the conch. Then the shell is washed up. The conch is then cut in a bangle shape to go through a scrubbing machine for smoothing its surface. Finally the motifs are crafted. Only a deft hand can produce the finest.

The motifs are images of nature, myth, traditional beliefs, rites and rituals. Popular motifs are dhaan chhora, motor daana, griho lakhmi, shabu dana, ek konkon etc. There are hundreds more --- dori patch, pachdaana, beni, shati lakhsmi, bandhan, shankhabala, juiful, golap, latabala, jaalfash, taarpach, uporbeni, do shapa etc.

There is another variety where gold is used on the shankha. These however are the luxury of the wealthy segment of society (S. Parveen, Daily Star, September 15, 2008).14. Khadi Reviving the Heritage