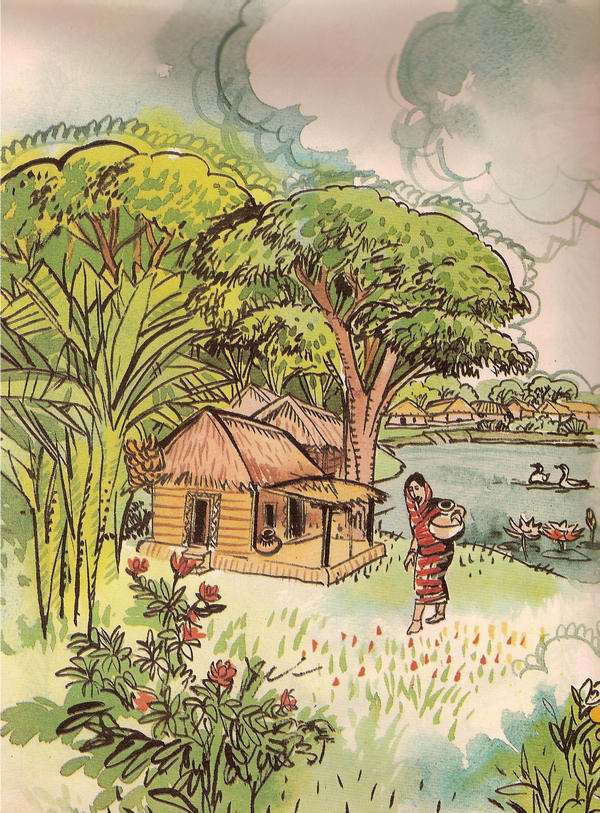

Jasim Uddin (1903-1976), who became one of the iconic poets of liberated East Pakistan, namely Bangladesh, was also heavily influenced by Prof. Dr. Dinesh Chandra Sen, under whom he worked as Ramtanu Lahiri Assistant Research Fellow from 1931 to 1937, collecting folk literature. His very first book of verse, Rakhali (shepherd) (1927) offered evidence of his passionate love and commitment to rural Bengal as a utopian and lyrical locus. Some of his most famous works were Naksi Kanthar Math (The Field of the Embroidered Quilt) (1929) and Bangalir Hasir Galpa INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.21 APRIL 2006 (Humorous Tales of Bengalis). Again, Jasim Uddin's deep involvement in non-communal socio-political movements championing the cause of Bengali language and literature gives his lyric and folksy poetry a keen edge of commitment and protest. His poems are popular as part of school curricula in West Bengal, India as much as in Bangladesh. Satyajit Ray records in his autobiography that he was taught in school by Jasim Uddin. Jasim uddin has written several nursery, poems, plays and songs for the children: The folk do not transcribe their own rhymes (or tales) nor disseminate them widely in a modern urban world, and thus the reception, recording, and propagation of the rhymes takes many forms. Folk rhymes are an important part of the Bengali folklore tradition, which has existed for over a millennium. While folk rhymes in most cultures are seen as secondary to other oral traditions such as folktales and ballads, they are given equal importance in Bengali folklore. Their long history makes discerning origins impossible, but Bengali folk rhyme can be studied in terms of collective creation, variation, social function and dynamism. |

|

|

The folk do not transcribe their own rhymes (or tales) nor disseminate them widely in a modern urban world, and thus the reception, recording, and propagation of the rhymes takes many forms.

Folk rhymes are an important part of the Bengali folklore tradition, which has existed for over a millennium. While folk rhymes in most cultures are seen as secondary to other oral traditions such as folktales and ballads, they are given equal importance in Bengali folklore. Their long history makes discerning origins impossible, but Bengali folk rhyme can be studied in terms of collective creation, variation, social function and dynamism. |

|

Jasim Uddin writes (Essays of Jasim Uddin Part II, 2001) :  |

|

| |

Amar Bari

|

Letter from Hashu  |

Paler Nao

|

|

Mamaer Bari (Uncle's House)  |

|

Alap  |

Ato Hashi Kothay Pelo  |

Khukir Sampati  |

Khokar Ghuri  |

Kabi o Chashar Meya (Poet and Farmers Daughter)  |

|

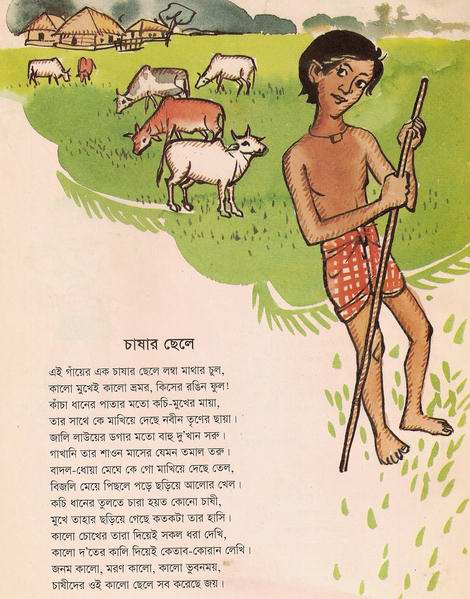

Chachar Chelay(Farmer's Son)  |

|

|

|

|

Bengali has a rich tradition of folklore and folk literature. This tradition is the creation of the rural folk, transmitted orally from one generation to the next. In addition to the rhymes that comprise the subject of this article, Bengali folk literature includes such forms as folktales, riddles, proverbs, maxims, and songs.

Folk rhymes exist in one form or another in most areas of the world. Examples are the nursery rhymes of Europe, the Mother Goose verse of America, and the warabe uta and komori uta of Japan. The origins of many Bengall folk rhymes are obscure, and are thought to be of considerable antiquity; certainly a large portion of them are known to have existed in the oral tradition for several centuries at least. This is a characteristic they share with the folk rhyme traditions found in most other cultures. Siddiqui quotes the famous folklorist M. Bloomfield as follows:

|

Last Modified: November 1, 2008

HomePlease View Sponsored Advertisements to Support this Site and Project

CONTENT

CONTENT

"Chhelebhulano Chharha," the first in a collection of essays on Bengali folklore entitled Lokashahitya [Folklore], published in 1907 by Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).(1) Tagore's views on folklore composition as expressed in "Chhelebhulano Chharha" are significant from the perspective of contemporary folklore scholarship. There currently exists no other complete English translation.(2) The essay is followed by a small collection of chharhas (rhymes) compiled by Tagore.

"Chhelebhulano Chharha," the first in a collection of essays on Bengali folklore entitled Lokashahitya [Folklore], published in 1907 by Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).(1) Tagore's views on folklore composition as expressed in "Chhelebhulano Chharha" are significant from the perspective of contemporary folklore scholarship. There currently exists no other complete English translation.(2) The essay is followed by a small collection of chharhas (rhymes) compiled by Tagore.