Back to Content

2.Gazir Gan, Pat, Puthi Pat

Today, many of us are ignorant of Gazir Gaan, Gazir Yatra, Gazir Pat, Puthi Pat, Kiccha-Kahini jari and so on and on. Saymon Zakaria has been travelling to different parts of Bangladesh to find out and let others know of what remains of the indigenous cultural performances, which still survive like the flickering light of a burnt away candle.

Gazir Pat- Scroll Painting - Method

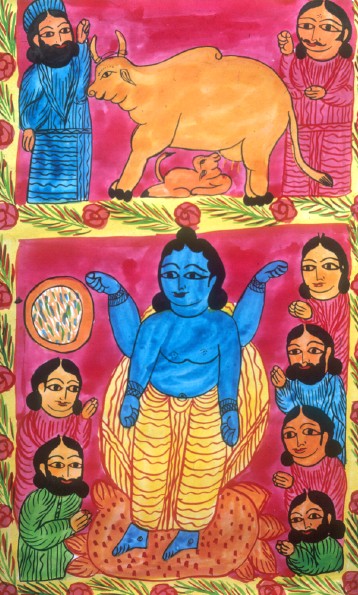

Gazir Pat a form of scroll painting; an important genre of folk art, practised by patuyas (painters) in rural areas and depicting various incidents in the life of Gazi Pir. Until the recent past, the narration of the story of Gazi Pir with the help of a Gazir pat was a popular form of entertainment in rural areas, especially in greater Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla, Noakhali, Faridpur, Jessore, Khulna and Rajshahi. Those who took part in the performance were members of the bedey community and Muslim by faith. Besides Gazir pat, there were other scrolls depicting well-known stories such as Manasa Pat (based on the goddess manasa), Ramayana Pat (based on ramachandra), Krishna Pat (based on Lord krishna) etc. The asutosh museum of indian art (Kolkata, India), Gurusaday Dutt Museum (Kolkata, India) and the Museum

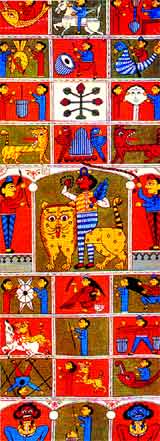

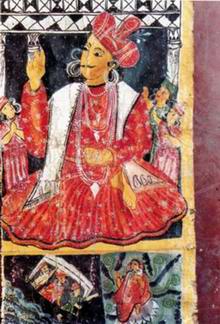

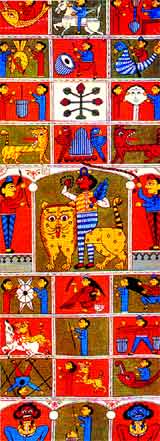

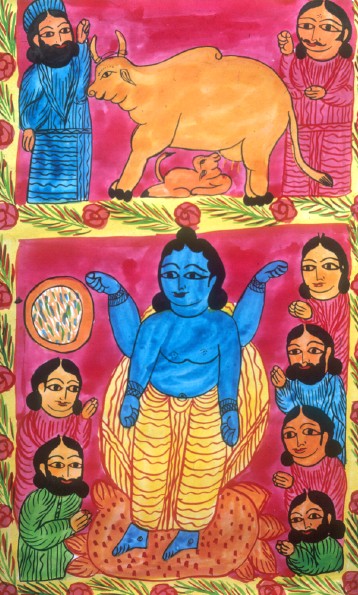

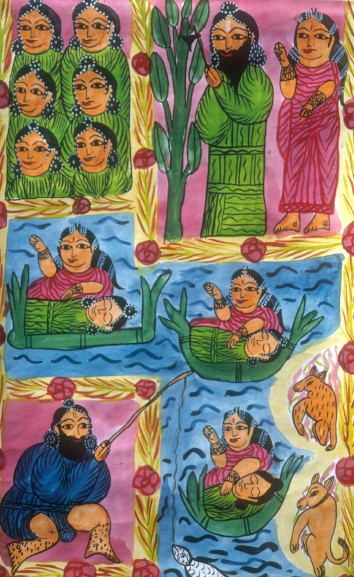

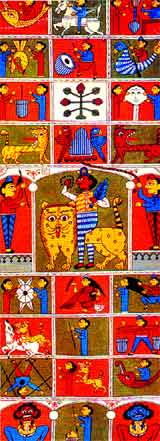

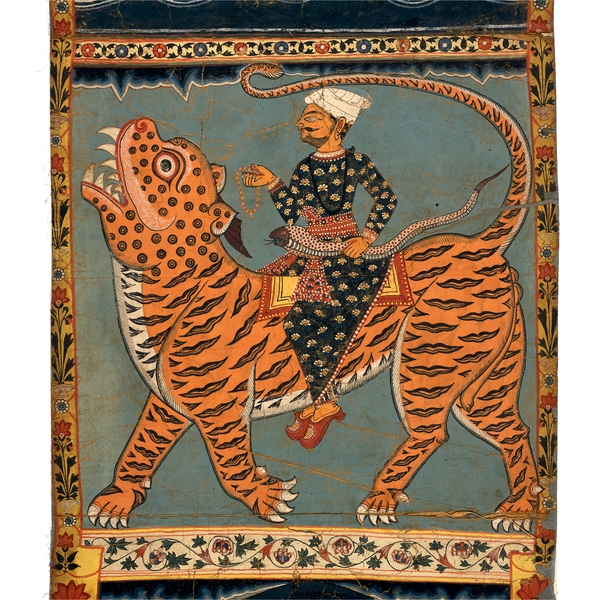

Gazir pat is usually 4'8" long and 1'10" wide and made of thick cotton fabric. The entire scroll is divided into 25 panels. Of these, the central panel is about12" high and 20.25" wide. There are four rows of panels above and three rows below the central panel. The bottom row contains three panels, each of which is5.25" high and 6.25" wide. The central panel depicts Gazi Pir seated on a tiger, flanked by Manik Pir and Kalu. The central panel of the second row shows Pir Gazi's son, Fakir, playing a nakara. The central panel of the third row shows Gazi's sister, Laksmi, with her carrier owl. The right panel of the second row shows the goddess Ganga riding a crocodile. In the bottom row, Yamadut and Kaladut, the messengers of Yama, are shown in the left and right panels. The central panel shows Yama's mother punishing the transgressor by cooking his head in a pot. As Gazi Pir is believed to have the power to control animals, a Gazir pat also depicts a number of tigers.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines, and small circles) are often used. The figures lack grace and softness. Some of the forms (such as trees, the Gazi's mace, the tasbih, (the Muslim rosary), birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, Kalu, Manik Pir, Yama's messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. There is no attempt at realism.

The traditional method of painting Gazir pat begins with the preparation of size from tamarind seeds and wood-apple. The tamarind seeds are first roasted and left to soak overnight in water. In the morning the seeds are peeled, and the white kernels are ground and boiled with water into a paste. The paste is then sieved through a gamchha (indigenous towel). The tamarind size thus obtained is then mixed with fine brick powder. In order to prepare wood-apple size, a few green wood-apples are cut up and left to soak overnight in water. The resultant liquid is strained in the morning, and the size is ready to use.

A Gazir pat is generally painted on coarse cotton cloth. The piece on which the painting is to be executed is spread on a mat in the sun. A single coat of the mixture of tamarind size and brick powder is then applied on the side to be painted, either by hand or with a brush made of jute fibre. After it has dried, two coats of size are applied on the other side of the cloth, which is then left to dry. On the side to be painted, another coat of a mixture of tamarind size and chalk powder is applied. When the cloth is dry, it is divided into panels with the help of a mixture prepared with wood-apple size and chalk powder. When the prepared cloth is dry, the patuya starts painting the figures.

The pigments were originally obtained from various natural sources: black was obtained by holding an earthen plate over a burning torch, white from conch shells, red from sindur (vermilion powder), yellow from turmeric, dull yellow from gopimati (a type of yellowish clay), blue from indigo. The patuya would make the brush himself with sheep or goat hair. Some of these techniques are still used today. However, the patuya usually buys paints and brushes from the market.

The tradition of Gazir pat can be traced back to the 7th century, if not earlier. The panels on Yama's messengers and his mother appear to be linked to the ancient Yama-pat (performance with scroll painting of Yama). It is also possible that the scroll paintings of Bangladesh are linked to the traditional pictorial art of continental India of the pre-Buddhist and pre-Ajanta epochs, and of Tibet, Nepal, China and Japan of later times. [Shahnaz Husne Jahan]

The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint, writes Robab Rosan

Although worshipping the images of Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint, writes Robab Rosan

Although worshipping the images of Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

There are some influences of Khijir Pir or Khawaj Khijir, a Muslim holly man considered as the protector of water, found in the story of Gazi Pir. To the worshipers of Gazi, this warrior-saint protected his devotees from attacks of wild animals and demons in the forests. In Bangladesh, particularly, in the regions of the Sundarban, the story and images of Gazi Pir had earned much popularity among the forest dwellers, like woodcutters, beekeepers and others. These communities still believe in the supernatural powers of the Pir and utter his name when they venture in to the forest.

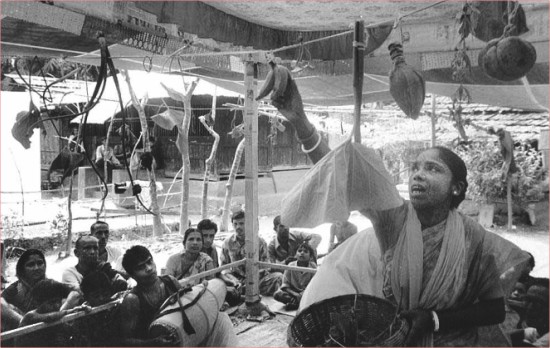

In the plains, Gazi is worshiped as the protector against demons and harmful deities and saves them from all sorts of dangers. The villagers usually call the gayens or folksingers, who know the story of Gazi Pir to sing the saint’s praise. The travelling storytellers, mostly belonging to the bede (gypsy) community, use a Gazir pat and pointing at the images on the pat, they narrate the power and prowess of the Pir in their singing verses. The devotees also hang the scroll paintings of Gazi in their houses to protect them from the influences of evil power.

The singers’ preaching created a demand for the pats among the devotees, irrespective of caste, creed and community and the pats had gained a huge popularity in the rural areas across the country, in the early years. Traditionally, the singers were Muslims while the patuas belonged to the Hindu religion. Sadly, at present, this combined form of art, paintings on pats and rendering of Gazir praise, has lost its purpose as a savoir from evil.

Gazir pat, though being considered as a nearly extinct art form, is gaining new ground. There were many patuas — hereditary painters of pats —who once existed in many regions of Bangladesh; now the number has drastically reduced. Until the recent past, the narration of the story of Gazi Pir with the help of a Gazir pat was a popular form of entertainment in rural areas, especially in greater Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla, Noakhali, Faridpur, Jessore, Khulna and Rajshahi.

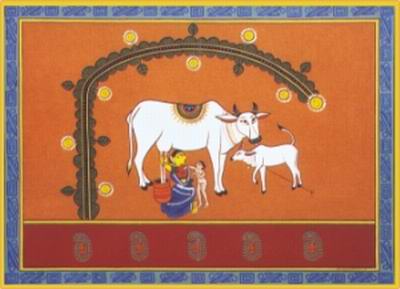

Gazir pat has specific images painted on a single canvas which have remained unchanged through the centuries. These images have been honoured as sacred symbols of good omen. There are twenty seven panels in a traditional Gazir pat, which measures 60 inches X 22 inches. The ankaiya (painter) follows the traditional styles in depicting the images. In the twenty-seven panels, the ankiya draws the images of a shimul tree; a cow; drum to depict triumph of Kalu Gazi; sawdagar or merchant; a deer being slaughtered; Asha or hope, the symbol of Gazi; Kahelia; Andura and Khandura; tiger; umbrella in the hand of Gazi’s disciple; Suk and Sari birds sitting on the umbrella; Lakhmi; charka, the spinning wheel; two witches; goala or milkman; mother of the goala; a cow and a tiger; an old woman beautifying herself; Baksila; Ganga; Jamdut; Kaldut; mother of Jam raja; and in the centre Gazi riding on a tiger. The singer or singers narrate sometimes the night long story, pointing at the characters, which appear in the twenty seven panels of the pat.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used in the pats. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines and small circles) are often used. Trees, Gazi’s mace, the tasbih or prayer beads, birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, his disciples Kalu and Manik Pir, Jama’s (the Hindu god of death) messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. Though there is no attempt at realism in the images of Gazir pats, the sort of painting has a time value as primitive work.

Among the adi patchitras or ancient paintings besides the Gazir pat, we also come across in history the Mahabharata pat, Ramayana pat, Muharram pat, Jam pat, Chaitanya pat, Manasa pat, Laxmi pat and others. Among the modern pats, one can see saheb pats, cinema pats and grameen pats.

Holding on to the tradition of painting Gazir pat with resilience is Shambhu Acharya of Munshiganj. His is the ninth generation of ankaiya. Shambhu, born in 28 Poush, 1362 BS (1956) at Kalendipara, Rikabibazar, Munsiganj, has learnt the art of Gazirpat from his father Sudhish Chandra Acharya. There may be other ankaiyas in other parts of Bangladesh pursuing this particular form of painting, but Shambhu has the privilege of claiming to have come from an unbroken line of patuas.

During 1980s, noted folk art researcher, Dr Tofael Ahmed saw a Gazir pat in the Ashutosh Musem in West Bengal, and read in the information that, that particular pat was the only existing pat in Bangladesh and West Bengal. After coming back to Bangladesh, Dr Ahmed started looking for Gazir pat in the rural areas. After visiting many places, Dr Ahmed, accompanied by Dr Hamida Hossain and artist Kalidas Karmakar, came to the village of Hajipur in Narshindi. There they met a huge group of bedes.

While talking about Gazir pat, with the bedes, singer Konai Mia, showed a Gazir pat rolled up in the boat. The owner of the pat, Durjan Ali, another bede singer, was not present at that time.

The team was overwhelmed with joy as they discovered a pat which would be an important link in the history of folk art in Bangladesh. When Durjan Ali came back he told them that he had bought the pat from a patuya, named Sudhish Achariya in Bikrampur (now Munsiganj) twenty years ago, in the 60’s.

Once he got the address of Sudhish, Dr Ahmed rushed to Munsiganj in search of the Acaharya and fortunately met Sudhish. But at the time the demand for pat had decreased and Sudhish had become more involved in making pratimas. Dr Ahmed pursued Sudhish to go back to painting Gazir pat, as this art was on the way of extinction.

Shambhu in his early life had learnt the art by watching his father work. But as the demand of Gazir pat fell and it became difficult to survive by selling pats. So he started earning a living by painting images of gods and goddess on the walls of Hindu temple. Shambhu even had a shop named Shilpalaya, where he used to paint signboards and banners to make ends meet.

Since his early life, Shambhu has been involved in depicting Gazir pats as a part of his familial tradition. ‘I used to help my father. At first he told me to put colours on the figures,’ said Shambhu. Shambhu used to draw different types of images on the walls of houses of his neighbours in his early life. They used to scold him, but sometimes appreciate him. Seeing his interest in paintings his father, Sudhish involved his son in this field and gave him lessons on this traditional work, which he had inherited from his ancestors. Besides depicting Gazir pats, Shambhu’s father also used to make pratimas, images of the gods and goddesses.

Shambhu’s father used to use gamchha as the canvas of the pats and used brushes, made of goat hair. He himself used to make the brushes. Today Shambhu uses markin cloth as the canvas for the pats. He uses brick powder, sindur, synthetic indigo, black soot collected from the flame of oil lamps; for the canvas, powder from tamarind seeds, egg yolk, gopi mati, and different kinds of oxides.

Shambhu's present

“To all the pats I have added Muktijodha pat, which tells the history of Bangladesh beginning with the battle of Plassey in 1757, the arrivals of the British and ending with our Independence in 1971, I am very happy with this huge achievement, even though the general public is yet to see it. Dr. Enamul Haq has done the geeti kabya for this pat,” he says.

With commercialism stinging everyone, Shambhu is content with less, “If I think of money than I will have to think of other things. My work is my aradhana, my religion. I am not keen on acquiring worldly possessions, and I don't want any publicity. I want to go slow but steadily. I want to make sure that I don't lose my head and do bad work,” he said.

For the love of art

Chakraborty feels that this art form needs to be popularised, solely because for the generation next.

“Shambhu's childhood, his influences, his desires, are quite different from his children's. It was bound to be so, because life is no longer easy and simple. Life now has so much to offer, there are so many options to choose from. Society today is so different from Shambhu's time, it's easy to be derailed. You need to earn some money to live a minimum comfortable life and if this oldest popular folk art doesn't bring in the bare necessities then it will be hard to keep it alive. An artist should be able to concentrate to do his work and not think of utility bills. In order to keep this tradition alive you need to popularise it, you need to have genuine patrons,” Chakraborty says passionately.

Till date Shambhu is the last patua, and whether his son and daughters, though already showing signs of being patuas, would keep the tradition alive is a hope against hope. However in this regards we would like to be optimistic as Shambhu and help his children to remain attracted to the profession of their nine generations.

Shambhu Acharya is a simple man who loves his roots and his simple, unglamorous life. He is afraid to dream big, yet not afraid to climb great heights through his work.

Patta Chitra Katha - traditional folk art of storytelling using visual language

Gazir Gaan

The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him. The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him.

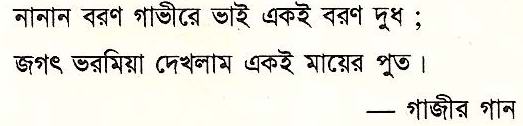

Gazir Gan songs to a legendary saint popularly known as Gazi Pir. Gazi songs were particularly popular in the districts of faridpur, noakhali, chittagong and sylhet. They were performed for boons received or wished for, such as for a child, after a cure, for the fertility of the soil, for the well-being of cattle, for success in business, etc. Gazi songs would be presented while unfurling a scroll depicting different events in the life of Gazi Pir. On the scroll would also be depicted the field of Karbala, the Ka'aba, Hindu temples, etc. Sometimes these paintings were also done on earthenware pots.

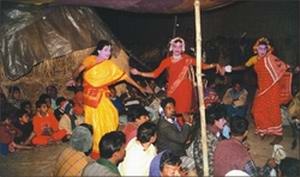

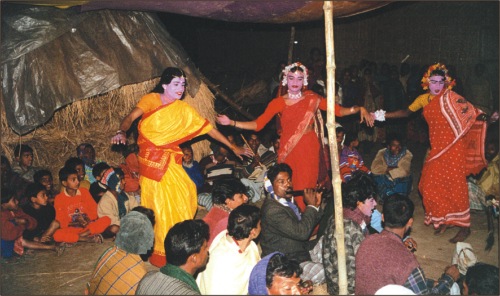

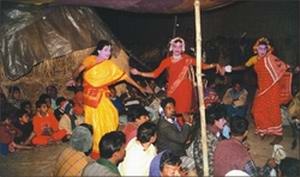

The Gazir Gaan singers and the instrumentalists took their seats facing north on the square shaped mat. Then commenced the starting ritual. As the lead singer implanted the symbolic icon, Gazir Asha (Hope of Gazi) north of the audience, music played on. Among the musical instruments were flutes, harmonium, juri or Mandira (a small hollow pair of cymbals) and the dhol (instrument of percussion which is not so much in width as a drum but longer in size). After the group instrumental, the lead singer presented a devotional song with his troupe accompanying him in stages.

If you come, Oh Merciful to rescue the destitute / (Merciful) Please take and make me cross

(I) do not offer my prayers, nor do I fast / Please have mercy and make me cross

(I) coming into this world / about you I have forgotten/ under the spell of infatuation . . .

Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion. Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion.

There are altogether 7 Paalas (episodes) in the Gazir Gaan performance:

1. Marriage 2. Didar Badshah 3. Dharma Badshah 4. Erong Badshah 5. Taijel Badshah

6. Tara Dakait 7. Jamal Badshah

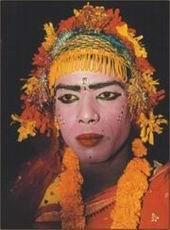

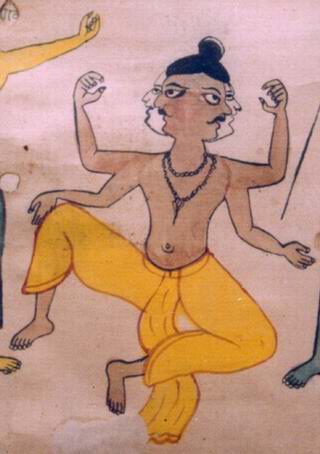

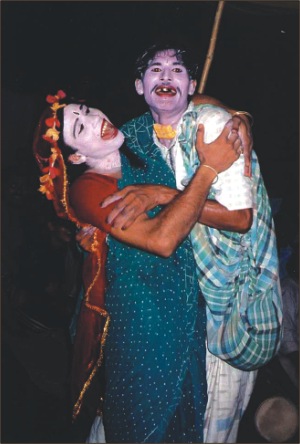

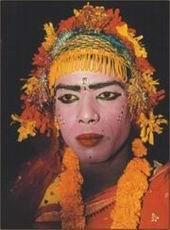

But the performance commences with the “Fokre Paala" depicting the story behind Gazi and Kalu's becoming ascetics after which continues seven episodes. Gazi is very serious and sincere in his work, while the character of his brother Kalu is more comical and he is the one who creates the humour through his role. Through his jeers and meaningless dialogue and activities he very skillfully takes the audience into the embedded sorrow and depth of the story. Here are some quotes from the "Fokre Paala". After the dance performed by the "Chukris", the lead singer stands up and delivers some introducing words in his local accent.

After the introductory words of the narrator, starts the instrumental and then the Dhua or starting chorus of the narrative passes from the lead singer to his members of the chorus.

Singer starts the main narration of the Fokre Paala of Gazi and Kalu and at the beginning he requests Kalu earnestly to become Gazi's companion in his quest of becoming an ascetic leaving behind the earthly pleasures and luxury. As this song ends Kalu comes up and takes part in dialogue (in verse and prose)based drama with the lead singer. The statements and their replies are rather nonsense, comic in nature and sometimes with the use of indecent words.

Gazi's knowledge and asks questions related to Sufi mysticism. Gazi answers satisfactorily and at one stage Kalu points out the asha of the Gazi. [The asha is one of the most holy ritual accessories that play an important role in the performance of the miracles of the saints (Pirs). It indicates the symbolic representation of a saint's supernatural power. During the Gazir Gaan performance, the asha is implanted in the ground and is not used in the performance. Other ritual accessories are used in Gazir Gaan and the offerings made to the saints in the performance are usually taken by the lead-narrator or singer himself on behalf of the saint.

At the end of the performance of each episode of the Gazir Gaan, the narrator asks the crowd which episode would they like to watch. The troupe performs accordingly because it is the mood of the crowd that matters to really feel the beat of the performance (Saymon Zakaria, August 30, 2004).

.

|

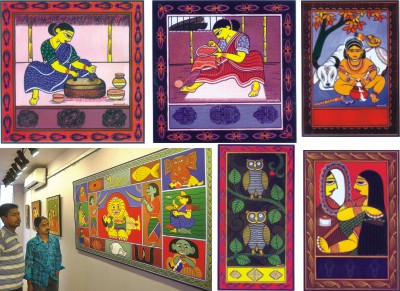

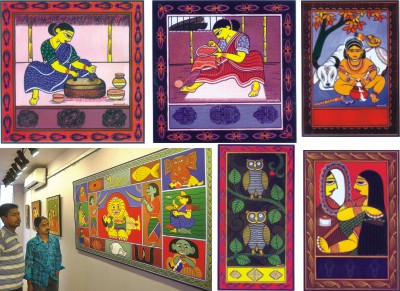

Among the indigenous Bangalee art forms, pata-chitra or scroll paintings stand apart in their choice of subjects, vibrant colours, unique lines and style of presentation. Painters of this form are called patua.

An exhibition of traditional pata-chitra by three patuas, Dukhushyam (Osman) Chitrakar, Rabbani Chitrakar and Rahim Chitrakar, is being held at DOTS Contemporary Arts Centre on Tejgaon-Gulshan Link Road.

(Daily Star, April 9, 2006).

The term Pata is derived from the Sanskrit word Patto, meaning cloth. In ancient times, before paper was introduced, artistes used to paint on thick cotton fabric. Usually mythical or religious stories were the themes. However, in time contemporary issues, animals and more found their place on these painting.

"Pata-chitra is perhaps the oldest art form in the Indian subcontinent and the tradition continues to this date. In fact, the art form can be traced all the way back to sixth BCE."

Besides being visual delights, the scroll paintings are also used in pat gaan or patua gaan. Through the medium of scroll painting, a choir narrates a story.

Most of the paintings in the exhibition illustrate myths, episodes from the Purana, Ramayana; some feature animals and imaginary monsters. The paintings have several sections so as to maintain a sequence. In the first segment the main characters, usually Gods and Goddesses, are portrayed boldly.

A painting featuring Raashleela of Radha-Krishna is stunning. Snake-like creatures with three heads on another one are interesting. Another painting shows three gruesome rakhkhoshi (females monsters) in their "full glory" -- teeth shaped like carrots sticking out, talons sharper than an eagle's -- staring back at the viewer as if to warn them to keep a safe distance.

Goddess Durga is the subject of several scrolls. One of the paintings show the Goddess smiting the beast Mahishashur. Vibrant colours -- yellow, indigo, bottle green, khaki, crimson and dark brown -- create a dazzling effect. Four Gods and Goddessess -- Ganesh, Karthik, Lakshmi and Saraswati -- ornate the corners of the painting.

The story of Goddess Kali stamping on God Shiva is the subject on a scroll. The Goddess is bare, as she is portrayed traditionally and painted in deep purple. In episodes from the Ramayana, Rama and Sita are seen getting married in the first segment. Other scenes featured are Lakshman cutting the nose of the monster, Suparnekha and Sita abducted and imprisoned by Ravana.

An interesting scroll shows fish carrying other fish in paalkis.

Bangladesh is home to long and rich folk tradition. Dr. D. P. Ghosh (1980) says, "two thousand and five hundred years ago, scroll painting or panel painting was widely used in this country." The art of Bangladesh influenced the art of the Far-East, especially the art of Java. In Bangladesh, folk painting is a part of vast folk culture, developed from time immemorial (Prof. R. Alam,2001).

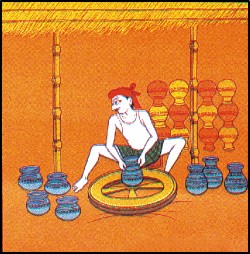

The patuas are artisans, who are now principally engaged in decorating pottery which is also a dying craft. Now a days we do not find any Patua in one time famous Patua colonies of Bengal.

In Bengali Chal Chitra (inverted shaped roof like design) are employed on the clay images. Chal Chitra are done by the village folk artists. This has become a dying art.

Ghat means water pitcher in Bangla. Manasa is the snake goddess. These ghats are made from clay on the potter's whell and then dried and burnt. All the Ghatsare absolutely folk in nature and primary colours are bold draughtsmanship are employed. The style of painting has affinity with ancient Egyptian and Minoan painting, especially in the depiction of eyes.

Potchitro or story telling through depicting images on canvas has always been a traditional form of art and entertainment. The trail goes a long way back to the Middle Ages when story telling was an important form of entertainment in Bengal. Poets told tales of gods, saints and the virtuous, of kings and queens, through their writings. Artists portrayed these verses through colours and motifs.

The age-old folk art survived centuries to tell the tale. It still continues to entertain the art enthusiasts.

Potchitro or story telling through depicting images on canvas has always been a traditional form of art and entertainment. The trail goes a long way back to the Middle Ages when story telling was an important form of entertainment in Bengal. Poets told tales of gods, saints and the virtuous, of kings and queens, through their writings. Artists portrayed these verses through colours and motifs.

The age-old folk art survived centuries to tell the tale. It still continues to entertain the art enthusiasts.

The exhibition displays 45 pieces of Raghunath's work depicting everyday life of the rural people and the popular motifs of Bengal.

Raghunath Chakravarty does not have any academic training. He did however found inspiration from his mother and later on from renowned potchitro artist Shambhu Acharya. The stroke of the brush came to him naturally.

“I learned from my mother. She used to paint potchitro and decorate the house with alpona whenever there was an occasion”, he said.

“From then on I had colours in my mind. I just started to compose in my head and started with a brush one day”, he added.

“I learned from my mother. She used to paint potchitro and decorate the house with alpona whenever there was an occasion”, he said.

“From then on I had colours in my mind. I just started to compose in my head and started with a brush one day”, he added.

Raghunath however personalised the art. From religious stories he moved on to everyday life of the rural people. From traditional practice of story telling on clay pots he moved to canvas. “I find it more attractive the lives of the ordinary folks, everyday struggle, the beauty of the rural landscape”, said Raghunath.

Raghunath's favourite theme is the eternal love between mother and child. In his work the theme keep coming back along with boat race, the weavers and the carpenters at work, rural wife's cooking preparation, the bangles seller lady, women fetching water, ethnic women at work and many more (S. Parveen, October 24, 2007).

The old folklore tells the story of Gazi Pir, a mythical warrior saint who battled demons, confronted the god of death, and worked miracles like restoring dead trees to full bloom, and getting dried-up cows to milk again. These and more such fantastic and colourful fables and legends have been immortalised through pat gaans and patchitra.

Patachitra is one of the earliest forms of popular art in Bangladesh. Dating from the 12th century, and existing even today these pats or scroll paintings narrated stories based on religious or moral themes for the entertainment of the village folks.

Painting of Shambhu

Shambhu is the son of Sudhir Acharya of Kalindipara area of Munshiganj district. Sudhir Acharya, who has been holding out the 400 plus year family tradition of painting on scrolls died in 1989 leaving the big responsibility of carrying out this underrated but rare form of art to Shambhu.

While his forefathers died almost unrecognised by the mainstream, Shambhu received some exposure, thanks to a handful of art-lovers who promoted him. His art works made it to the Spitz Gallery in London on July 11, 1999 at the Bangladesh Festival

The tales of Ramayana, Mahabharata, Muharram, Rass lilla, Monosha Mongol, Sri Krishna and Gazi pir usually being the subject matter of these folk paintings that narrate their stories frame by frame. The patuas or pat artists supplemented their illustrations with pat gaans or music ballads.

Needless to say, Bangladesh with all its colours and vivacity is the place of this indigenous art form; at least we can safely claim this because the earliest sample of pat preserved in the Ashutosh Museum in Calcutta, which is over a hundred year old has its roots stuck deep in a quiet village in Bikrampur

Back to Content

3. Manasa Mangal ritual

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture.

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture.

Patuas, like the kumars, started out in the village tradition as painters of scrolls or pats telling the popular mangal stories of the gods and goddesses. For generations these scroll painters or patuas have gone from village to village with their scrolls or pat singing stories in return for money or food. Many come from the different villages of Bengal. The pats or scrolls are made of sheets of paper of equal or different sizes which are sown together and painted with ordinary poster paints. Originally they would have been painted on cloth and used to tell religious stories such as the medieval mangal poems. Today they may be used to comment on social and political issues such as the evils of cinema or the promotion of literacy.

Mangal kavyas are auspicious poems dedicated to rural deities and appear as a distinctive feature of medieval Bengali literature. Mangals can still be heard today in rural areas of West Bengal often during the festivals of the deities they celebrate, for example Manasa puja in the rainy season during July-August when the danger of snake bite is at its peak. Interestingly, it is the mangal stories connected with this particular art form that provide us with some of the earliest clues about the worship of clay images in Bengal.

The two most famous poems in this respect are the Chandi Mangal and the Manasa Mangal. In the Chandi Mangal of the Bengali poet Mukundarama Chakravarti (16th c), known as Kavikankana, the village goddess Chandi takes on the form of the Puranic deity Mahisasuramarddini (Durga) before the startled eyes of the hunter Kalketu and his wife.

Chandika took the form of Mahisasuramarddini

In eight directions the Ashtanayikas shone forth

Chandika took the form of Mahisasuramarddini

In eight directions the Ashtanayikas shone forth

Her right foot rested on the back of a lion

Her left foot on the back of the demon Mahisha

With her left hand she held Mahisha's hair

With her right hand she placed her trident in his chest

On her left side shone her matted locks

Her headress encompassed the whole circle of the sky

Bracletes and armlets adorned her ten arms

In this form she receives puja from the whole world

A noose, a goad, bell, mace and bow

These five weapons gleam in her five left hands

A sword, discus, trident, spear and brightly-shining arrows

In her right hands gleam these weapons

To her left is Karttikeya, to her right Ganesa

Above, Shiva rides on the head of a bull

To her right is Laksmi, to the left Sarasvati

Facing her, deities sing various hymns

Her limbs outshine molten gold

The colour of her three eyes outcolours blue lotuses

And her face outshines the autumnal moon.

(Kavikankana Chandi)

What this mangal poem hints at is that the style of Durga images seen today in the clay images of Bengal was already popular in the 16th c. Durga is popularised as the beleagured wife of the farmer god Shiva. She may be the mighty awe-inspiring goddess who kills demons, but she is also the compassionate mother or Ma and the devoted daughter who returns home during the autumnal festival of Durgotsava. Throughout mangal literature, the village deities are shown as very accessible figures who communicate freely with mortals and share their griefs and delights.

Tha main part of the mangal concerns the fate of Lakhindar and his bride Behula. Manasa warns that Lakhindar will die on their wedding night. So Chando has an iron room built to keep out any snakes that might kill his only son. However, Manasa persuades the architect to leave a gap big enough for one of her deadliest snakes to squeeze through at night and bite Lakhindar as he sleeps. Behula wakes up too late to help her newly-wed husband.

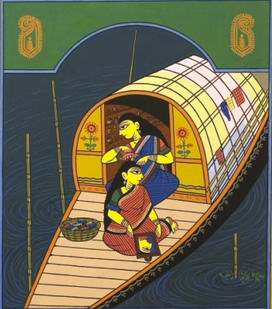

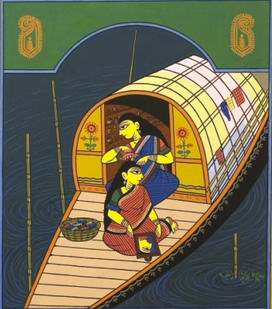

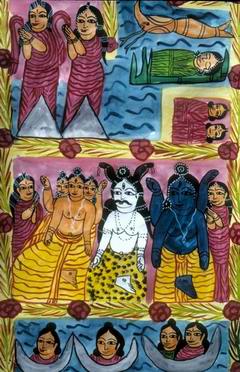

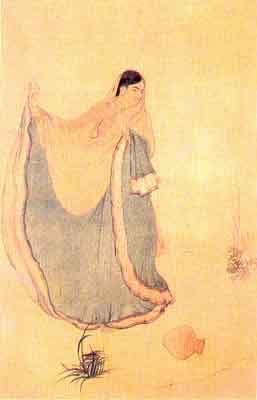

In this pat the snake goddess Manasa sends a poisonous snake to kill the hero Lakhindar while his wife Behula looks on helplessly. The iron room made to protect them on their wedding night proves useless.

The distraught Behula scolds Chando for his quarrel with Manasa and returns her wedding gifts. Instead of cremating her husband's body and scattering his ashes in the river as is the Hindu custom, she sets off downriver in a desperate bid to persuade to gods to revive her husband so that she avoids the fate of being made a young widow

Manasa pat shows how Behula sets off downriver on a raft made of banana bark carrying her husband's corpse on her lap hoping to persuade the gods to revive Lakhindar. On the way she meets the fisherman Goda who taunts her but Behula replies that she worships only the mother Manasa and she floats off again downstream.

Further on, she visits the city of the gods where she meets the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva who are impressed by her skills as a dancer and washerwoman to the gods. Shiva decides to persuade Manasa to revive Lakhindar and his six brothers in return for persuading Chando to worship the snake goddess.

The Snake Litanies

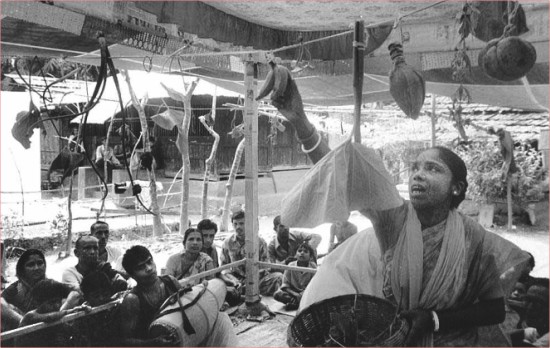

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later.

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later.

Behula

Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life.

Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage. Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life.

Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage.

In Hinduism, Manasa is a naga and goddess of fertility. She is popularly known as the goddess of wish fulfilment and one who protects against snakebite. She is also associated with the earth and higher knowledge. Though she is venerated mostly in eastern India.

She is probably a pre-Aryan goddess but this tale is of more recent vintage and comes from Bengal where she is most revered and tells how she gained recognition for herself as a potent member of the Hindu pantheon.

When Manasa approached Chand, he refused to worship her. This infuriated Manasa, and she killed all his sons. After this event, Chand's wife Sonika gave birth to their seventh son Lakhinder (also referred as Bala). Manasa's wrath had not been pacified even by the time when Lakhinder's marriage to Bihula was fixed.

She vowed to kill him on the Suhaag Raat (The night after wedding, when bride and groom sleep together for the first time). To counter the threat, Chand planned to construct an iron room for Lakhinder's Suhaag Raat. However, Manasa threatened the blacksmith as well, and asked him to keep a small pinhole in the room. As nobody noticed this hole, In the night, Manasa sent a very thin snake to enter the room through the pinhole. Once inside the room, this snake turned into a Cobra and bit Lakhinder, killing him instantaneously. Bihula overcame grief and built a boat to go to Heaven to present this injustice to gods. Lakhinder was then revived by the gods. During the return from Heaven, Bihula managed to persuade Chand to worship Manasa. Chanda grudgingly agreed to worship her with his left hand. To this day, Manasa is the only Hindu goddess worshipped by the left hand. In the Anga region, she is also known as Bishahari and worshipped to prevent snake-bite related deaths. The boat created by Bihula was made up of jute straws (Manjusha) and paper. This led to development of Manjusha art, which is now on verge of extinction.

|

Royani:

Royani is the music of Manasas. It is the music of Behula.” At Meeradi's words I come back to the topic of Manasa, she seemed to make perfect sense. Of course, the songs were about the two women- Manasa and Behula. Both of these women have had to overcome many obstacles to be well respected in society. Men do not understand the pain and anguish these women have had to go through.

One woman has many forms-the mother, the daughter, the sister.The whole performance was about the self-image and self-perception of these women. In that way, the show was kind of autobiographical.

The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula.

The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula.

The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

...The Bridal Chamber of Behula is stand in the south 2 k.m. from Mohaastan garh, Rangpur, Bangladesh.

"Many years ago I collected different types of quilts, dolls , 'Patachitra' 'scroll painting , Pat Patua, Gazir Pat - scroll pictures of Gazi, Monosa , pupet, alpana etc from different villages of Bengal. Friends advised me to make an exhibition. Gaba da displayed the items beautifully at the roof of Rabinra Nath Tagore's Jorashako House. Rabinranath Tagore carefully observed all the items and Abinranath Tagore was overwhelmed with the exhibition. Rabinranath Tagore said that I want to keep an exhibition of folk culture at Santiniketan. My collection began to increase day by day and I did have any space to keep the collection. I asked again Rabinranath Tagore to receive the collection for Santiniketan. He said he would ask Nandolal Basu to collect the items. But Nandolal Basu did not show any interest!

"Many years ago I collected different types of quilts, dolls , 'Patachitra' 'scroll painting , Pat Patua, Gazir Pat - scroll pictures of Gazi, Monosa , pupet, alpana etc from different villages of Bengal. Friends advised me to make an exhibition. Gaba da displayed the items beautifully at the roof of Rabinra Nath Tagore's Jorashako House. Rabinranath Tagore carefully observed all the items and Abinranath Tagore was overwhelmed with the exhibition. Rabinranath Tagore said that I want to keep an exhibition of folk culture at Santiniketan. My collection began to increase day by day and I did have any space to keep the collection. I asked again Rabinranath Tagore to receive the collection for Santiniketan. He said he would ask Nandolal Basu to collect the items. But Nandolal Basu did not show any interest!

In Bengali, "Pat" means "scroll" and "Patua" or "Chitrakar" means "Painter". The origin of the painted scrolls is very ancient. We could find some in the Pharaohs' graves in Egypt. In India the first description of these painted scrolls can be found in a sacred text dated 200 B.C.

In Bengali, "Pat" means "scroll" and "Patua" or "Chitrakar" means "Painter". The origin of the painted scrolls is very ancient. We could find some in the Pharaohs' graves in Egypt. In India the first description of these painted scrolls can be found in a sacred text dated 200 B.C.

The style too is handed down the generations. Patua, Patidar, Pata are the names by which a chitrakar is commonly known. He is a poet-painter-singer. He rhymes a narration around an episode of some Hindu mythology that imparts a moral lesson. He paints the sequences in a series of rectangular frames in vertical format as a scroll painting. To the clientele, he unfurls the scroll frame by frame as his narration set to tune proceeds. The moral lesson makes listeners aware of the vices and virtues of life.

The style too is handed down the generations. Patua, Patidar, Pata are the names by which a chitrakar is commonly known. He is a poet-painter-singer. He rhymes a narration around an episode of some Hindu mythology that imparts a moral lesson. He paints the sequences in a series of rectangular frames in vertical format as a scroll painting. To the clientele, he unfurls the scroll frame by frame as his narration set to tune proceeds. The moral lesson makes listeners aware of the vices and virtues of life.

Shambhu Acharya can trace his interest in arts and crafts back to nine generations (450 years). His family did paintings of not only Gazir Pot (scrolls illustrating the myth of the Muslim saint Gazi) but Mahabharata, Ramayana, Behula- Lokhindor Kahini, Sri Krishna and Muharram Pot (based on the life of Hussain and Hassan). A pat, Shongho explains, is a story, and a potobhumi is a series of stories that revolve around a hero.

Shambhu does stories of both Hindus and Muslims. Gazi, he says, the subject of many of his paintings was a powerful Muslim general with a metaphysical force, who tamed wild animals, and has a following among the gypsies. He is specially associated with the tiger and is often presented as riding a tiger. He was revered by both Hindus and Muslims and had an assistant called Kalu. Shongho has done 27 panel paintings with Gazi as his subject. He makes his canvases by layering markin cloth with brick powder, tamarind juice and egg yolk. He has also used various oxides and black soot.

Shambhu Acharya can trace his interest in arts and crafts back to nine generations (450 years). His family did paintings of not only Gazir Pot (scrolls illustrating the myth of the Muslim saint Gazi) but Mahabharata, Ramayana, Behula- Lokhindor Kahini, Sri Krishna and Muharram Pot (based on the life of Hussain and Hassan). A pat, Shongho explains, is a story, and a potobhumi is a series of stories that revolve around a hero.

Shambhu does stories of both Hindus and Muslims. Gazi, he says, the subject of many of his paintings was a powerful Muslim general with a metaphysical force, who tamed wild animals, and has a following among the gypsies. He is specially associated with the tiger and is often presented as riding a tiger. He was revered by both Hindus and Muslims and had an assistant called Kalu. Shongho has done 27 panel paintings with Gazi as his subject. He makes his canvases by layering markin cloth with brick powder, tamarind juice and egg yolk. He has also used various oxides and black soot.

The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint, writes Robab Rosan

Although worshipping the images of Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint, writes Robab Rosan

Although worshipping the images of Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him.

The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him. Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion.

Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion.

Potchitro or story telling through depicting images on canvas has always been a traditional form of art and entertainment. The trail goes a long way back to the Middle Ages when story telling was an important form of entertainment in Bengal. Poets told tales of gods, saints and the virtuous, of kings and queens, through their writings. Artists portrayed these verses through colours and motifs.

The age-old folk art survived centuries to tell the tale. It still continues to entertain the art enthusiasts.

Potchitro or story telling through depicting images on canvas has always been a traditional form of art and entertainment. The trail goes a long way back to the Middle Ages when story telling was an important form of entertainment in Bengal. Poets told tales of gods, saints and the virtuous, of kings and queens, through their writings. Artists portrayed these verses through colours and motifs.

The age-old folk art survived centuries to tell the tale. It still continues to entertain the art enthusiasts.

“I learned from my mother. She used to paint potchitro and decorate the house with alpona whenever there was an occasion”, he said.

“From then on I had colours in my mind. I just started to compose in my head and started with a brush one day”, he added.

“I learned from my mother. She used to paint potchitro and decorate the house with alpona whenever there was an occasion”, he said.

“From then on I had colours in my mind. I just started to compose in my head and started with a brush one day”, he added.

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture.

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture. Chandika took the form of Mahisasuramarddini

In eight directions the Ashtanayikas shone forth

Chandika took the form of Mahisasuramarddini

In eight directions the Ashtanayikas shone forth

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later.

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later. Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life.

Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage.

Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life.

Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage.

The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula.

The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula.

The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

When we talk about patchitra, first of all, the images of Kalighater pats come in our mind. This genre of painting developed in the nineteenth century which flourished in the market places around the Kalighat Mandir on the bank of the Ganges in Kolkata. But according some historians, older than the Kalighater pat were Gazir pats which most probably emerged around the 16th century. Unlike the Kalighater pat, the uniqueness of Gazir pat is of profound importance and influence in the history of painting and literature in Bengal both in subject and form. The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint.

When we talk about patchitra, first of all, the images of Kalighater pats come in our mind. This genre of painting developed in the nineteenth century which flourished in the market places around the Kalighat Mandir on the bank of the Ganges in Kolkata. But according some historians, older than the Kalighater pat were Gazir pats which most probably emerged around the 16th century. Unlike the Kalighater pat, the uniqueness of Gazir pat is of profound importance and influence in the history of painting and literature in Bengal both in subject and form. The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used in the pats. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines and small circles) are often used. Trees, Gazi mace, the tasbih or prayer beads, birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, his disciples Kalu and Manik Pir, Jama (the Hindu god of death) messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. Though there is no attempt at realism in the images of Gazir pats, the sort of painting has a time value as primitive work.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used in the pats. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines and small circles) are often used. Trees, Gazi mace, the tasbih or prayer beads, birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, his disciples Kalu and Manik Pir, Jama (the Hindu god of death) messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. Though there is no attempt at realism in the images of Gazir pats, the sort of painting has a time value as primitive work.

One of the most striking exhibits in the current British Museum exhibition Myths of Bengal is the beautiful Gazi scroll - not just for its rich colours and vivid figures, but because it illustrates the enriching coexistence of two of the world's great faiths. Images of Hindus making puja offerings are juxtaposed with those of Muslims making similar offerings at the tombs of their saints (pirs). It shows how a remarkable, syncretic culture emerged in which the tombs of many pirs became places of pilgrimage for both Hindus and Muslims.

One of the most striking exhibits in the current British Museum exhibition Myths of Bengal is the beautiful Gazi scroll - not just for its rich colours and vivid figures, but because it illustrates the enriching coexistence of two of the world's great faiths. Images of Hindus making puja offerings are juxtaposed with those of Muslims making similar offerings at the tombs of their saints (pirs). It shows how a remarkable, syncretic culture emerged in which the tombs of many pirs became places of pilgrimage for both Hindus and Muslims.

Shambhu Acharya, the patua, comes from such a long line of dedicated patuas of Bikrampur. His family has been working in this art form for the last eight generations. But it's only the art of Shambhu, the 9th generation of patuas, which has recently come to the limelight.

The modern urban people of today are striving to find the roots of their traditional culture. Perhaps this well help to establish the art of patachitra once again with all its glory and popularity'.

Shambhu Acharya, the patua, comes from such a long line of dedicated patuas of Bikrampur. His family has been working in this art form for the last eight generations. But it's only the art of Shambhu, the 9th generation of patuas, which has recently come to the limelight.

The modern urban people of today are striving to find the roots of their traditional culture. Perhaps this well help to establish the art of patachitra once again with all its glory and popularity'.

We have dolls as playthings for children; marionettes for play-acting of larger size; life -size, and sometimes larger than life, caricatures, effigies and clowns.

We have dolls as playthings for children; marionettes for play-acting of larger size; life -size, and sometimes larger than life, caricatures, effigies and clowns.  This is a typical wooden doll found all over Bengal. It varies in its decorations and colours in different districts but the form remains the same.

This particular one was bought in Kenduli in Birbhum district. The colour of the head, arms and feet is yellow. Upper garment covering the body below the waist is blue and green. The details and decorations of the figure are drawn with black and red thick brush lines.

This is a typical wooden doll found all over Bengal. It varies in its decorations and colours in different districts but the form remains the same.

This particular one was bought in Kenduli in Birbhum district. The colour of the head, arms and feet is yellow. Upper garment covering the body below the waist is blue and green. The details and decorations of the figure are drawn with black and red thick brush lines.