Natural Indigo (Indigoferra tinctoria) and the unfinished Fight for Freedom

0 father come let us go

To the field to plough,

Place the ploughs on oxen shoulders

and Push, push, push.

We who bring out food

From the depth of earth,

We who provide food for the whole world

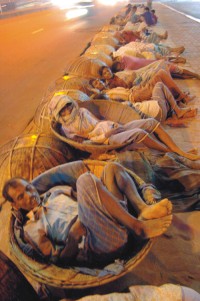

Why can't we eat can any one tell us ?

My wife has hanged herself

She could no longer bear hunger,

Now I plough deep into soil

In hope of seeing her again.

We plough the fields

Our bosom is also flayed

But from the fields we get harvest

None from the scarred bosom.

We shall plough no more the earth for rice

But to see how far it is to the graves.

Jasim Uddin (A popular folk song in Bengal- HMV record. Kolkata)Please View Sponsored Advertisements to Support this Site and Project

A fragment of madder-dyed cotton fabric found at the Harappan sites indicates the use of natural dyes by the people of Mohenjodaro as back as 3000 B.C. The tinctorial properties of vegetable substances, recognised in the Vedic period, particularly in the Atharvavedic and the succeeding periods ranging from 1000 to 500 B.C. were kala or asikni (possibly indicating indigo), maharanjana (sunflower), manjistha (madder), lodhra (symlocis racemasa) and haridra (turmeric).

The dyestuff introduced in the post-Vedic period ranging from 500B.C. to 3rd century A.D. included Kumkuma (saffron) and nila (indigo) among the plant products; krmi (kermes) and rocana (bright yellow substance prepared from cow’s urine) among the animal substances; gairika (red-ochre) among minerals; and khanjana (carbon black).

The period from the Classical Age to Medieval Period of Indian history acknowledges the tinting capacity of a number of vegetable substances as well as of metals and minerals. The Medieval Period was marked by the discovery of the colour fixation property of tuvari (alum) and the process employed for the extraction of the colouring principles from the dyestuff. The late Medieval Period (18th century) introduced the application of iron mordant for the fixation of colours like blue, green and violet. It is during the Mugal Period that the shades of a number of colours in different tones came into the field of dyeing with natural dyes.

Indigo has outlasted the travails of history because it is one of the most "colourfast" natural dyes. The blue remains beautiful, even if it fades. The range of colours based on indigo is extensive. Even among natural dyes, indigo has special qualities. It does not need a mordant to make it fast. It is compatible with all types of natural fibre. It can be used in combination with other dyes to produce a wide range of colours.

Experts say that Egyptian mummy clothes from the third millennium B C (not futuristic AD!) had borders of indigo dyed stripes. Blue was a predominant colour in the funeral wardrobe of Tutenkhamen. Blue is the only colour found in the earliest dyed linen fragment of ancient Israel and Palestine. The linen wraps of urns containing the Dead Sea scrolls carried symbolic geometric patterns in blue. Babylonian texts talk of garments dyed in blue and there is even one which gives the method for dyeing in indigo. The Bible speaks of "blue clothes and embroidered work" traded by the merchants of Sheba. Blue silk fragments of the third millennium B C have been found in China.

The word Indigo is derived from the Greek Indikon and the Latin Indicum, meaning a substance from India. Evidence for the use of Indigo in India before the medieval age is based on the writings of a trader in Egypt in the first century A D. India was then the pivot of trade both Westwards and Eastwards.

Indians were highly accomplished in textile arts. As with other subjects such as mathematics, much earlier on, knowledge from India was dispersed through the trade route. Indigo, the last natural dye, was a highly priced commodity on the "Silk route". From 1600 onwards, the documents of the East India Company mention the production of indigo in India and its export. Gujarat and Sind were the major sources then. From mid 17th century, Europeans arriving on India's East Coast picked up finished textiles, cotton and silk, rather than the raw material indigo. Indigo was a major dye used in these fabrics.

. It made fortunes for farmers in mediaeval times. Since then, synthetic dyes have taken the time and toil out of colouring textiles and natural dyes have faded out of use. But natural fibres are making a comeback in the fashion industry and natural fibres demand a natural dye.

Indigo and Espionage in Colonial Bengal

Indigo is a dyestuff that was a major item of international trade from the 16th to the late 19th century. Although it has various other uses apart from dyeing (mainly medicinal uses), in this book, the type of indigo that has been described is the one used for dyeing. The word indigo points to South Asia. It derives from the Greek word 'indikon', which means, 'from India'. Ancient Greek imported their blue colourant from India.

The trade of Indigo from Asia was controlled by the Portugese in the middle of the sixteenth century. The Spanish were their main competitors and were eager to get around the Portugese supplies. They did this by taking indigo plants from Asia to their new colonies in Central America. Soon hundreds of commercial indigo establishments emerged, particularly in El Salvador and Guatemala. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, Central American indigo became a very successful product. Central American indigo was being exported in huge quantities to Spain, Peru and Mexico. Spain received its indigo and exported to Britain and the Netherlands with extra duties. Decline set in partly as a result of heavy taxation by the turn of the nineteenth century. The global indigo market was characterised by such imperial competition.

In their Caribbean and North American colonies, the French and the British set up successful indigo industries. The Dutch set up their indigo industries in Java. Export quality indigo was being produced in many parts of the world by eighteen hundred. Suppliers from the Philippines, Java, India, Mauritius, Egypt, Senegal, Venezuela, Brazil, Guatemala, Haiti, and, South Carolina competed in the world market. Globalisation of indigo production became a success commercially but not without a human disaster. Indigo production was a labour inte sive process. In an increasingly competitive global indigo market, only those who could keep their cost of production low by employing cheap labour could make a profit.

Central American indigo trade collapsed by the turn of the nineteenth century. There were two chief reasons for this. Firstly, there was a war between Spain and Britain in 1798 and these two countries previously dominated the market for Central American indigo. The second was a fifty-percent drop in production caused by locust attacks in 1801. In the seventeen-ninety's, Haiti's indigo industry went into decline. There were slave revolts in Haiti leading to Haiti's independence from France. Indigo exports from Haiti to France came to a standstill. The British Caribbean planters switched from indigo to sugar. After the American Revolution of the seventeen seventy's the British lost their control over North American indigo. By eighteen hundred, many regions, which, were indigo producers, either abandoned indigo production or reduced international trade, causing a crisis in the global indigo market. Bengal was one of the surviving regions, unhindered by this sharp drop in global indigo production and trade. It was a new dominating region in indigo production. Not only could Bengal indigo be produced in large quantities because of the ample labour that was available there, but also the quality of Bengal indigo surpassed that of many countries.

It is at this point of the book that we are introduced to the agro-industrial espionage, the rivalry between imperial powers like France and Britain who were competing in the indigo market with the help of their colonies, and the Darrac report. The French saw an opportunity to rival indigo from British Bengal by planting Bengal indigo in Senegal, which, was then a French colony. Darrac being the former Chief of French Settlement at Dhaka for six years was in a good position to provide the report on indigo production in Bengal. There was little scope for the French to use French India as the location for a new indigo industry. Darrac's report covers that aspect as well when he discusses the similarities or dissimilarities of indigo production methods in India and Bengal. The climate of India is different from that of Bengal. There is no flooding in India and there, land prices are higher. Indian soil did not produce the fine quality of indigo as that produced in Bengal. There were a number of differences, which limited the French from aspiring in India.

Darrac goes on to describe the quality of the soil in Bengal. The soil in Bengal either had silt deposits or a sandy surface both of which were favourable for indigo plantation. In India however, the regions with salt-based soils were friendlier for indigo production. Darrac then moves on to describe the entire production process of indigo in Bengal (with references to and comparisons with India). He begins from the way the soil is ploughed and then describes the varieties of indigo seeds. He goes on to tell us about the sowing, weeding, harvesting, transport, fermentation, beating, draining, boiling, filtering, pressing, and, finally how indigo cakes (as they take their final form) are cut and encased. Darrac also describes the tanks, furnaces, drying rooms and reservoirs that aid in the production process. He provides detailed measurements of the equipment at the factories, the exact numbers of men that were used for the task along with illustrations. Darrac's was not a blunt response to the French Government. He analyses the situation in Bengal to provide all the pros and cons of the possibility of indigo production in French Senegal. This is not only a good book on the history of indigo production that covers a dimension which so often remains unexplored in such depth as is provided in this book, but also a piece of inspiring writing that will aid indigo producers in various countries, not to mention the indigo enthusiasts. I will recommend the book to those interested in Asian history, history of Bengal, social anthropology, indigenous knowledge and development perspectives.

Based on an uprising by farmers in Bengal during 1889, a chapter known in history as Neel Bidroho (Indigo Revolt), the play features the struggles of the masses in British India. Because of the Industrial Revolution in England, the demand for indigo was on the rise, and a major share of it happened to come from the subcontinent. In Bengal, farmers were forced to grow indigo plants -- instead of rice or other major crops -- by the British rulers. Despite repeated complaints and peaceful protests from the farmers, the English turned a deaf ear to them, implementing cruel punishments. Eventually the poor and the deprived united in their protest against the British and their cronies, zamindars (landlords).

Medical use

The substance that they all contain is indican, a by-product of the plant's own metabolic process that helps the plant to resist pest attack and discourages grazing animals. In humans, indican is reportedly anti-bacterial, and will reduce fevers and swellings, and fight skin infections. But the market as traditional medicine is modest in comparison to that for dyeing cloth.

Manriquie, who journyed through Dhaka in 1640, goes on to tell about the city's legendary fine muslin which ranked among the greatest industries in the world and made up most of the export trade. Manrique did not exaggerate the wealth and prosperity of the city.

Many reliable documents including colonial records" suggest that throughout the seventeenth and three-quarters of the eigh- teenth centuries, the wealth and prosperity of the city advanced at a cumulative rate. Washbrook even suggested that the export of textile goods from Bengal threatened to de-industrialise the European and Mexican textile industries to the point that state action, in the form of tariff barriers, had to be taken against them even during the eighteenth century (Washbrook, 1988:60).The production of muslin (textile) flowered under state patronage in Bengal and it became the chief source of wealth and prosperity for the city, catering for markets as widely spread as South-east Asia and Europe. Its cotton and textile industries attracted many labourers from the rural areas, as well as traders from the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Europe who settled there long before Britain seized power over Bengal.

Dhaka once Manchester of India fallen to one of the poorest cities

The East India Company's profit earned from the exploitation of Bengali textile workers was a landmark in the development of a process which I would call repeasantisation in Bengal. Thousands of textile workers gave up their traditional employment and fled from the city to the countryside. The vacuum which was created was filled by the import of textile goods produced in the mechanised factories of England (Allen,1912:107). The British administration imposed further restrictions and duties on the production and export of textile goods in Bengal. This policy not only shut the British market to textile goods from Bengal, but Bengal itself became the market for British textile goods. Thus the colonial system, in a short time, transformed an independent productive unit into a market dependent on its imperial centre (Ahmed, 1986)

For Dhaka the consequences were disastrous. By 1801 the population of the city declined to 200,000 and by 1838 the number was further reduced to 68,000. A census taken in 1867 showed that Dhaka had been reduced to a population of 51,000. In 1840 Sir Charles Trevelyan of the East India Company reported:

The peculiar kind of silky cotton formerly grown in Bengal, from which the fine Dakha muslin used to be made, is hardly ever seen; the population of the town of Dacca has fallen from 150,000 to 30,000 or 40,000 and the jungle and malaria are fast- encroaching upon the town ... Dacca, which used to be the Manchester of India, has fallen off from a flourishing town to a very poor and small one.Of course during the same period a quite opposite development was occurring in the cities of England. Between 1838 and 1856 the number of textile workers in Manchester had increased at the rate of 56 per cent.

In India, as early as 1812-13, Buchanan, while making his famous survey in Shahabad in Bihar, had observed that the moneylenders were the chief instruments of making peasants life miserable. Later, as the indigo plantation was introduced in Bengal, peasants’ oppression increased a great deal.

The East India Company, an important corporation at the time (starting in the 15th century), exported to England, its home base, more indigo than any other product from India.

Till the second half of the 18th century, Bengal did not play a major role in the indigo tale. It was only subsequently that the East India Company "promoted" the cultivation and processing of indigo in Bengal and Bihar. In the 19th century, Bengal was the world's biggest producer of indigo in the world! An Englishman in the Bengal Civil Service is said to have commented, "Not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood". Indigo was part of the national movement. Champaran in Bihar witnessed indigo riots in 1868. In 1917 Gandhiji himself launched an enquiry into the exploitation of indigo workers.

As the demand for indigo rose in the textile industry and sowed indigo in its place. However, those who performed the planters refused to pay the full amount stipulated in the contracts (Kling, 1966).

The British textile industry was largely dependent on North and Central American sources of dye. During the American revolution the British lost their American sources. As a result, the east india company was encouraged to grow indigo in Bengal (Kling, 1966).

From 1830 onward the demand for indigo increased tremendously in the textile factories in Europe and Dhaka became the main distribution centre (Bertocci, 1977)

Destruction of of the textile industry in Bengal and reorganisation of agricultural policy went along side by side after colonial intervention. The establishment of both private property rights in land by the Permanent Settlement Act and the forces commercialisation of agriculture benefitted rich peasents (Jotdars). Mukherjee (1971) argued that the 'self-sufficient village economy' of Pre-British Bengal, which was based on 'peasent production', 'disintregrated' and was improverished by colonial intervention.

The British found land revenue as the primary source of income in India and they increased it at regular intervals. The question which had bothered them in the beginning was from whom to collect the revenue.

This was to be settled with the persons who were to be regarded as the owners of land, for in England the owner paid the revenue. In India, however, the revenue was paid by zamindars and all sorts of middlemen who were well-established in the country-side, but were not owners of the land.

The British recognized these revenue payers as the owners of land and left the cultivators to their tender mercies. The British felt it handy to collect revenue from a limited number of landlords rather than from innumerable cultivators, merely for the convenience of extorting the maximum amount with the minimum expenditure.

Moreover, the creation of Zamindari system was to provide a social base for the colonial power in strengthening its hold over the country.The Permanent Settlement of 1793 converted the revenue collectors into landowners in Bengal.

The zamindars had thus been selected as the persons to settle with “not as a matter of chance, but as one of deliberate policy.” ----Baden Powell, The Land System of British India. As the British dominions in India expanded, the British extended individual ownershi of land as a means to retain their hold on the growing dominions.

The imperial, political and economic considerations played their part in the determination of British policies in the annexed areas. The Permanent Settlement, with all its merits, contained one handicap in as much as it kept the company’s income static. So new experiments were taken up in the revenue policy such as Ryotwari system in Madras and Bombay, temporary zamindari settlements in the Punjab, and central provinces,etc. A s a resul of British land policy the land-holdings changed hands from cultivating owners to non-cultivating owners.Traders and mahajans invested money in lands and soon the abuses of absentee landlordism came into existence.The Pemanent Settlement imposed in Bengal in 1793 to collect revenue and to ensure the supply of raw materials or to facilate the flow of agricultural products for British industries. In 1770 a terrible famine resulted in bengal that took ten million Bengali lives, one third of the population (Dufferin, 1888)

Pemanent Settlement fundamentally altered agrarian Bengal from traditional self-contained, motionless, egalitarian society to one with a dynamic peasantry - new class of landlords.

Even after more than 50 years of independence, the situation of the poor peasents has not changed:

Northern consumers who love the Bangladeshi shrimp and the cheap price - because they're not paying the costs of these mangrove forests which people have managed for hundreds of years. And the World Bank came and told them that the only way they could solve their balance of payments problem was only by going into the export of non-traditional items: shrimp, turtles, things which change everything related to the environment.

Three decades after the launch of the Green Revolution, agricultural scientists are now discovering that chemical pesticides are a complete waste of time and money. They have realized the grave mistake only after poisoning the lands, contaminating the ground water, polluting the environment, and killing thousands of farmers and farm workers.

Is it true that the best way to fight hunger, protect the environment and reduce poverty in Africa is by relying on Green Revolution crop varieties, and using more imported farm chemicals, plus genetic engineering and free trade? This is precisely what powerful institutions in Washington and elsewhere are prescribing for the continent, yet each of these elements could actually worsen, rather than improve conditions for Africa's poor majority (Institute of Food and Development Policy and the University of California at Berkeley, USA, 2002)'East is East and West is West, and never shall the twain meet'- imperial arrogance

"We westerners will decide who is a good native or a bad, because all natives have sufficient existence by virtue of our recognition. We created them, we taught them to speak and think and when they rebel, they simply confirm our views of them as silly children, duped by some of their western masters.'

This imperialistic arrogance generated nothing but anger and hatred, attitudes ultimately reflected in powerful and expressive indigenous works of art.The farmers revolt had a second aspect, which was religious in colour. It started as a religious purification movement but soon changed its character, and without taking into consideration to which religion the Jamindar, landlord and moneylender belonged to, they started attacking on them. Finally their general outburst came out in the form of series of revolts against the British imperialism throughout the country.

The revolt that distinguished itself as being based on purely economic issues, and having nothing to do with religious persuasions, was the Indigo Revolt of 1860, directed against European planters whose exploitation had pushed the peasants to the wall. A surprising aspect of this revolt was the support it enlisted from the Bengali intelligentsia, who had otherwise shown no interest in the earlier peasant movements. The Indigo Revolt elicited much support from a Bengali journalist, whose speeches and writings made a definite contribution to its cause. It also inspired a playwright to produce the ..nost popular play of the time, which in turn contributed a great deal to the nationalist movement in Bengal.

Neel Darpan (The Indigo Mirror), a play by the Bengali writer Deen Bandhu Mitra also painted a pathetic picture of the atrocities inflicted upon indigo plant workers, resulting in the imposition of the Dramatic Performance Act by the colonizers, an act aimed at suppressing native voices from speaking out against the British Raj.

The Neel (indigo)agitation of Bengal in 1859-60 is one of the largest farmer agitation of the modern times. European farmers had a monopoly over Neel farming. The foreigners used to force Indian farmers to harvest Neel and to achieve their means they used to brutally suppress the farmer. They were illegally beaten up, detained in order to force them to sell Neel at non-profitable rates. In 1860, Bengali writer Deenbandhu Misra published a play called Neel darpan which depicts the story of oppression faced by the Indian farmers cultivating Neel. Finally in 1859, the farmers revolted, and declined to cultivate Neel. They faced the brutalities unleashed upon them by the landlords and the British officers with courage and determination. At this moment, the educated elite of Bengal stood by its farmers.

The Government was forced to appoint a committee which was to dwell into the corrupt practices related with this system and suggest means to reduce it. Yet the oppression of landowners and agitation of the farmers against them continued. In 1866-68 Darbhanga and Champaran in Bihar witnessed agitation by Neel farmers.

Mutiny : Farmer agitations

The main jolt of the imperialistic operation was faced by the farmers, as a result they fought against the British rule in each and every step. Sadly though, references to such struggles are not easily available.

The Neel (indigo)agitation of Bengal in 1859-60 is one of the largest farmer agitation of the modern times. European farmers had a monopoly over Neel farming. The foreigners used to force Indian farmers to harvest Neel and to achieve their means they used to brutally suppress the farmer. They were illegally beaten up, detained in order to force them to sell Neel at non-profitable rates. In 1866-68 Darbhanga and Champaran in Bihar witnessed agitation by Neel farmers.

The farmers of Jessore (Bangladesh) revolted in 1883 and again in 1889-90. Seventh decade of the 19th century witnessed large scale land related problems. This time it was East Bengal. The landowners of East Bengal were infamous for the oppression of the artisans of Bengal. They used to illegally confiscate their crops, properties and land. Bengali farmers had a long tradition of opposition to oppression, in 1782 for the first time the Bengali farmers stood against the East India Company's taxman Devi Singh.

In 1872-76 they joined associations which were against such revenue collection methods. They attacked the landowners and their go-downs and looted them. They were finally suppressed when the Government directly interfered in the matter. Inspite of this, small scale agitation continued. It ended when the Government finally promised to legislate laws to protect their interests.

The situation deteriorated to such an extent that in 1874, they got together in Pune and Ahmednagar district in order to chalk out their future course of action. They decide on socially boycotting such moneylenders and landowners. At various places, they seized various legal documents related to their properties from the moneylenders and burnt it. The Government suppressed it using artillery and cavalry. In other parts of the country various other such agitations took place among which the revolt by Mopila farmers of North Kerala against the oppression let loose by Genimi landowners. Between 1836-54 they related 22 times.

Fresh revolts took place again in 1873-80. In similar way the farmers in the plains of Assam revolted between 1893-94 against high revenue rates. Farmers declined to pay at such high revenue rates and were finally suppressed by the Government which used all the brutal methods in its book.Morgan House, Extravagant Life of Wealthy Indigo-owner

WBTDC Tourist Lodge (Morgan House) (55384), a few km from the center of town, is a nice older building with rooms with bath and hot water for Rs 900/1250 including meals. It is in an excellent location and has a really nice garden.

During my two weeks visit, I stayed at Morgan House, a stately colonial relic with a gracious, grey stone façade, festooned with lichen and bougainvillaea, large immaculately clean rooms with high ceilings, soft-spoken and liveried waiters. A wall-to-wall glass window in my room framed a breath-taking view of the Eastern Himalayas. On my first evening, luxuriating in this plenitude, a Scotch-and-soda in hand, I felt euphorically divorced from the frenzy and frenetic lunacy of my everyday world. My cup of joy filled to overflowing...(Don Alney)

If a person has ever gone through Neel Darpan written by Deenabandhu Mitra, he would jump at the idea of seeing and spending a few days in a place where a wealthy indigo-owner used to live at the turn of the 20th century . Morgan House in Kalimpong in West Bengal is such a place.

Ensconced in the mountain of Durpindara, now surrounded by the Kalimpong Cantonment area and overlooking the valley downward, Morgan House is a heritage house with a history of its own. Built on 16 acres of land in the hill three kilometres off the centre of Kalimpong, Morgan House looks straight in the face of Kanchanjhangha Range. It was built around 1930 to commemorate the wedding of the daughter of an Indigo owner with a jute baron Mr. Morgan.

Just before the advent of mighty Himalayan winter in the month of November, the House with its thick rectangular stone block wall to resist outside change of weather and its wooden floors and steel-framed glass-paned windows surprisingly keeps a normal temperature inside. One can view the snow-capped ranges of Kanchanjhangha glowing in the morning sun in golden colour while lying in bed from early morning till noon if the sky is clear. At dawn the glow is reddish gold reminding one of Oman gold immediately. (The gold mines in the kingdom of Oman lies side by side with copper mine, hence Oman gold has a distinct red hue of its own). The sunlight slowly descends on the lower ranges as if a huge torch is lighted up from the sky to help the viewer to get a crystal clear view of the valleys downwards and displays the border with Sikkim. The humongous brewery of Danny Denjappa there shines in the sun from the West Bengal border.

Kalimpong is a city of flowers, orchids and cactus. The orchids starts blooming from December onwards and stays up to June. Rare varieties of cactus is found, nurtured and grafted there.

Nowhere in the world, I have visited so far, I have seen this profusion, combination and varieties of flowers growing wild with exquisite colour and shape. In Morgan House alone I have counted five hundred varieties of flowers. The house has Roman paved ways from different angles and the split level stairs at the garden introduces one with umpteen flowers and foliage. The stone wall of the house is covered with vine and several other flowering creepers. The stunning panoramic beauty with riot of colour cannot be explained by writing.

So, it is no wonder the place where Morgan House is situated is called “Chandralok”, meaning the land of moon, thus giving it a romantic touch. Chandralok includes the vast cantonment area, the army Golf course, the Tibetian Gumpha with big establishment, government lands and several view-points. The view-points show the West Bengal-Bhutan border, the confluence of three rivers, Rimki from Kalimpong, Teesta from Tibet and Reiling from Bhutan. From high altitude down below, rivers with their blue waters and white sands amidst green valleys are a sight which is best felt but cannot be described. It is the Himalayan ambience in the Tarai region which communicates with the soul (Mira Rahman, Weekly Holiday, December 10, 2004)..

But can we imagine how much blood, sweat and tears of the poor forced indigo famers poured into this house? This house should not be used as tourist lodge but for the memories of indigo farmers.

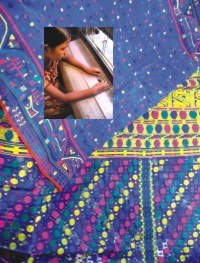

The indigo plant is a leguminous plant that is used as an inter-crop. It gives nitrates to the soil. The process of extracting indigo dye is quite complicated and involves a lot of labour. The plants are soaked in a vat or a sloping tank. Two or three people actually get into the tank and paddle the water continuously for two to three days. The blue rises to the top. The water is drained out. The remaining blue substance is taken out and made into cakes. The blue that emerges cannot be matched. It is believed that the term "blue collar" worker is derived from the indigo workers, who used to wear the cheap blue cloth.

Dye Produced in India-Bangladesh

The cut plant is tied into bundles, which are then packed into the fermenting vats and covered with clear fresh water. The vats, which are usually made of brick lined with cement, have an area of about 400 square feet and are 3 feet deep, are arranged in two rows, the tops of the bottom or "beating vats" being generally on a level with the bottoms of the fermenting vats. The indigo plant is allowed to steep till the rapid fermentation, which quickly sets in, has almost ceased, the time required being from 10-15 hours.

The liquor, which varies from a pale straw colour to a golden-yellow, is then run into the beaters, where it is agitated either by men entering the vats and beating with oars, or by machinery. The colour of the liquid becomes green, then blue, and, finally, the indigo separates out as flakes, and is precipitated to the bottom of the vats. The indigo is allowed to thoroughly settle, when the supernatant liquid is drawn off.

The pulpy mass of indigo is then boiled with water for some hours to remove impurities, filtered through thick woollen or coarse canvas bags, then pressed to remove as much of the moisture as possible, after which it is cut into cubes and finally air-dried."Indican appears to be a by-product of the plant's metabolism and to be not particularly stable for in harvesting the stem of the plant it is necessary that the leaf be immediately subjected to bacterial action lest it disappears. The normal commercial process requires that the stems be submerged in water in a suitable vat contaminated with bacteria for a period of 10-15 hours during which time the indican is hydrolysed to glucose and indoxyl which pass into aqueous solution. The liquor is separated and aerated by beating to promote oxydation [sic] of indoxyl to indigotin, or indigo-blue, which settles out as an insoluble faecula at the bottom of the vat." (Burkill 95 v.3 p.363)

"Indigo-blue [indigotin] and indigo-red [indirubin] are isomerous, but not interchangeable. Their proportions vary according to the conditions of the processing. Slow oxidation in an acid medium favours the latter, while rapid oxidation in an alkaline medium the former." (Burkill 95 v.3, p.363).

Indigotin Production from Plant Material:

Method 1: Based largely on The Woad :

Chop up freshly cut leaves (and stems in some species) fairly finely and put them into a container that can withstand heat (large glass jars are good) Pour enough boiling water to cover the leaves into the jar. Cover and let stand for about an hour. Strain the liquid through muslin to remove all plant bits. Add alkali (lye, potassium hydroxide, lime, or ammonia) to the strained liquid to reach a pH of 9 or higher. If you don't add too much alkali at a time you can test it by hand--your fingers will feel greasy or soapy starting around pH9-10. Have some vinegar standing by to rinse your fingers with. Use a whisk, egg beater or electric blender to mix air into the liquid. As you do this the indigo will oxidize and come out of solution. Allow the liquid to sit until the blue indigo has sunken to the bottom of the container. Carefully pour the liquid off the top, leaving the precipitated indigo in the bottom. Add more water and repeat to rinse the indigo. Pour the indigo into a shallow pan (preferably non-stick) to evaporate. When indigo has dried you can grind it and use it just like any other indigo. Mound of Goo Fermentation and Couching Based largely on A Modern Herbal: Woad: Treatment of the Crop :

Dry the freshly cut leaves very slightly in the sun. Pound or grind them into a paste consistency. Form paste into a mound outside in the air, but protected from rain. Do not disturb the mound for about two weeks as it ferments--especially, do not break the crust that dries on the outside After about two weeks mix the paste (and crust) together and form it into lumps or cakes Dry the cakes in the air Before using the dye break up the cakes, mix them with water to form paste, and ferment them again "The colour is brought out by mixing an infusion of the Woad thus prepared with limewater"--probably meaning you should then treat the fermented paste like the fresh leaves in the Steeping recipe above (pour on boiling water, let sit, filter/decant, add alkali, beat in air to oxidize, let indigo settle, decant, rinse, decant, dry) The process of extraction of dye is also difficult because of the strong odour that the vat emanates. Also, the vat should not be exposed to sunlight. It is buried in the ground, with only the neck showing. There is also a belief in India that working on an indigo extraction unit makes a woman sterile. Hence, only men used to undertake this job.It is easy to dye cotton with indigo dye, but the process becomes difficult with silk or wool. Enough now about the pedestrian aspects of indigo dyeing.

Complexity of the processing

The great drawback to indigo has always been the length and complexity of the processing required. In simple terms, the plant has to be picked, without bruising the leaves, and then soaked, while fresh, in warm, alkali water to release the indican which must then be oxygenated to produce blue indigo.

In mediaeval times the whole process required twelve weeks or more and workers had to stand in huge vats of noxious liquid, whisking it with staves or bare hands. Even today, the traditional technique requires at least seven days but, in Guinea, indigo is now being produced in powdered form after a few hours of anaerobic fermentation of indigofera followed by filtration, decanting and drying in the sun.

The techniques have been developed by PERTEGUI (Study and Research Project on Guinea's Indigenous Technologies) which is an IDRC-supported project. The work of Guinean dyers is now well known throughout West Africa.

Dyers can buy powdered indigo on the market, thus avoiding the extraction stage and saving considerable time. Moreover, there has been an eight to ten-fold decrease in solid and liquid wastes from exhausted dye baths - a clear environmental improvement - and the nauseating fumes produced by conventional dye baths have also been eliminated, improving working conditions.

El Salvador was once a major producer of indigo under Spanish rule and elderly people remember the industry, which continued after the colonists left. Now, under a German backed project, the old Spanish dye tanks have been cleaned out and are being used to produce indigo again, but by more efficient methods.

In the East of England, traditional home of the indigo-bearing brassica, woad, extraction is also more efficient now than when it was used to paint the faces of local warriors to terrify invaders. Following major investment which, in itself, indicates the expected market, a mobile processing unit, taken to the field, turns green leaf to blue dye in 30 minutes. British indigo growers are delighted that the biggest dyer in the country is expressing great interest in reverting to natural indigo.

Film:

Natural Indigo Dye Fermentation Process 1

Natural Indigo Dye Fermentation Process

Natural Indigo Dye Fashion Show

FIZA FASHION SHOW

Chha Gaye Baadal Neel Gagan Par Asha Bhonsle & Mohammad Rafi

In the beginning of the 20th century synthetic indigo drove natural indigo production to commercial extinction, and the synthetic product now supplies the 80,000 tonnes of indigo used every year to dye blue denim.

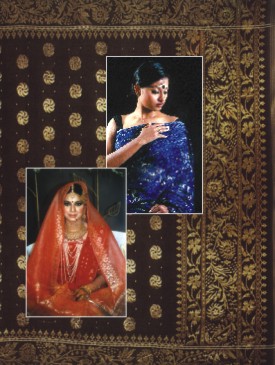

All that glitters is not gold. So too, all that synthetically dyed handloom clothes and garments is not good for health and environment. A very good alternative is there. And it is nothing but natural dyes, specially vegetable ones.

Photo: All textile mills of Bangladesh polluting rivers (Balu river)The East India Company, an important corporation at the time, exported to England, its home base, more indigo than any other product from India. The tremendous profits from indigo which Germany missed out on acted as an incentive to manufacture synthetic dyes.

During the worldwide jeans boom in the second half of the 20th century, demand by the general public was met not by natural indigo, but by synthetic indigo. This color transcended time and place to become popular throughout the world. It goes without saying that until the invention of synthetic indigo, this color was limited to the clothing and other dyed goods of a certain class of Europeans. It is probable that this colour became fixed as a status symbol for the upper classes by association with Chinese ceramics.

This is due to the fact that synthetic dyes are both cheaper and simpler to use. But in the fag end of the 20th century witnessed many side–effects of using synthetic dyes. The production of synthetic dyes is not pollution-free and such dyes are carcinogenic. It is now a well-established fact that the use of synthetically dyed clothes and garments is likely to induce many diseases among the users. A section of G-8 countries has banned the import of synthetically dyed clothes in the interest of its citizens.

There exists a very widespread belief that "vegetable" or "natural" dyes are superior to "synthetic" dyes, and that a rug woven with "vegetable" dyes is in all ways a better carpet than a rug woven with synthetic colours. In fact, it is usually not possible to separate the dyestuffs used in many rugs into these two neat categories, and even were this possible, some "vegetable" dyes are much more fugitive in colour or even damaging to the wool than the "synthetic" dyestuff that yields the equivalent shade.

In general, "vegetable dyes" are taken to be an indication of a more traditional, more rural, more country rug weaving, while synthetic dyes are considered more characteristic of city or commercial production. Even this distinction breaks down, however, when one realizes that synthetic azo dyes (an acid direct dye that yields yellow or orange-red) were introduced to many weaving areas between 1875 and 1890, and by the turn of the century were available to many rural weavers.

Common vegetable dyes:

The most common colours of red, black, blue, violet, green, and yellow are obtained from plants and minerals native to the subcontinent. Indigo plants are processed and traded in the form of dried cakes that are used to create different shades of blue. Red dye is extracted from alizarin-producing plants and trees, such as the chay or the madder, and yellow from turmeric or saffron (the latter mostly for silks). Black is created by mixing indigo with an acid substance such as tannin.

The most commonly used vegetable dyes are indigo (originally obtained by extracting and fermenting indican from the leaves of the indigo plant), madder (produced by boiling the dried, chunked root of the madder plant in the dye pot), and larkspur (produced by boiling the crushed leaves, stems, and flowers of the larkspur plant). These dyes produce, respectively, dark navy blue, dark rusty-red, and muted gold. Long ago dyers realized that as more wool was dyed in a single dyepot, colours became weaker and weaker.

The first dyeing produces a deep, strong colour. Subsequent dyeings in the same dyepot produce lighter, softer colours (like the three shades of indigo, madder, and yellow.

Dyers also quickly learned to combine colours to produce different hues. There is, for instance, no "vegetable" dye material that yields green (an important colour if you're interested in weaving a floral design!). First dyeing wool blue, then dyeing it again with yellow, does produce a green colour.

Colour From this material Notes red to orange root of the madder plant Rubia tinctoria bright red to burgundy cochineal (dried insect carapace) often from Dactylopius coccus ight blue to navy indigo (extracted from the indigo plant) Indigoferra green double-dye of larkspur and indigo pale yellow to yellow-brown larkspur or isparuk (a flowering plant) Delphinium sulpureum black tannin, oak tree galls, iron this dye is often damaging to wool Dye History from 2600 BC to the 20th Century (S. Druding, 1982)

2600 BC Earliest written record of the use of dyestuffs in China 715 BC Wool dyeing established as craft in Rome 331 BC Alexander finds 190 year old purple robes when he conquers Susa, the Persian capital. They were in the royal treasury and said to be worth $6 million (equivalent) 327 BC Alexander the Great mentions "beautiful printed cottons" in India 236 BC An Egyptian papyrus mentions dyers as "stinking of fish, with tired eyes and hands working unceasingly 55 BC Romans found painted people "picti" in Gaul dyeing themselves with Woad (same chemical content of color as indigo) 2ND and 3RD Centuries AD Roman graves found with madder and indigo dyed textiles, replacing the old Imperial Purple (purpura) 3rd Century papyrus found in a grave contains the oldest dye recipe known, for imitation purple - called Stockholm Papyrus. It is a Greek work. 273 AD Emperor Aurelian refused to let his wife buy a purpura-dyed silk garment. It cost its weight in gold. Late 4TH Century Emperor Theodosium of Byzantium issued a decree forbidding the use of certain shades of purple except by the Imperial family on pain of death 400 AD Murex (the mollusk from which purpura comes) becoming scarce due to huge demand and over harvesting for Romans. One pound of cloth dyed with Murex worth $20,000 in terms of our money today (Emperor Augustus source) 700's a Chinese manuscript mentions dyeing with wax resist technique (batik) Vegetable Dyeing Technique

The most commonly used vegetable dyes are indigo (originally obtained by extracting and fermenting indican from the leaves of the indigo plant), madder (produced by boiling the dried, chunked root of the madder plant in the dye pot), and larkspur (produced by boiling the crushed leaves, stems, and flowers of the larkspur plant).

These dyes produce, respectively, dark navy blue, dark rusty-red, and muted gold. Long ago dyers realized that as more wool was dyed in a single dyepot, colours became weaker and weaker. Dyers use this notion of depleated dyes to their advantage. The first dyeing produces a deep, strong colour. Subsequent dyeings in the same dyepot produce lighter, softer colours.

There is, for instance, no "vegetable" dye material that yields green (an important colour if you're interested in weaving a floral design!). First dyeing wool blue, then dyeing it again with yellow, does produce a green colour. If you look closely at the green colour in a vegetable-dyed rug, you will commonly see that the colour is uneven, more blue-green in some areas, and more yellow-green in others. This is because of the double-dyeing technique.

There is a bright prospect for cultivation of natural indigo in Madhupur of Tangail and Phubaria and Muktagacha of Mymensingh districts. Indigo is used mainly for dying cotton, silk, wool and other natural fibre used for making cloth, carpet and a host of other costly and fashionable products. Natural indigo is environment friendly and better than synthetic indigo. But its cultivation can not be expanded as synthetic indigo, imported mainly from India, has flooded the market and is sold at much lower prices, according to people involved in its production, preparation and marketing. Scarcity of seed and lack of other facilities also are obstacles to its production. But its cultivation in large scale can create employment opportunities for rural women and meet the country's demand.

Cultivation of indigo plants in 2000 under a project titled 'Nilkamol', involving Garo people at Jalchatra village in Madhupur of Tangail. Initially it brought 0.87 acres of land under cultivation. As the experimental cultivation was successful, it brought 12 acres of land under the cultivation in 2001. Next year, it started commercial cultivation at the village. Garo farmers cultivated indigo on 20 acres of land. But in 2003, the cultivation shrank to 12 acres as the farmers did not get seeds and other facilities. The cultivation increased this year.

Indigo is produced from leaves, which can be harvested three times a year. Cultivation during March-April and harvesting during August- September is more profitable, he said. A farmer can easily earn Tk 6000 to 7500 from one acre of land in a season. The investment is Tk 1500 to 2500. The sources said many farmers in Madhupur, Muktagacha and Phulbaria have shown interest for indigo cultivation but MCC could not supply seeds and provide them other facilities, they said. Interest is growing among farmers because its cultivation is easy and cheap.

"But as synthetic indigo has flooded the market and it is much cheaper. So our natural dye can not cope with the situation", Arun Kumar said. One kilogram of synthetic indigo dye is sold at Tk 600 to Tk 700 while natural dye is sold at Tk 1000, he said. Natural dye produced from indigo leaves is of better quality because its colour is bright and long-lasting, they said.

Arun Kumar also told this correspondent that MCC produced 155 kgs of indigo last year (2003) but the whole quantity is yet to be sold because cheaper Indian synthetic indigo has flooded the market. If this situation continues, they would be compelled to abandon their project, he said (A. Islam, Daily Star, December 11, 2004).

Indigo back to Bengal

Long gone are the days when the farmers refused to sow a single seedling of indigo plant and faced oppression from the British rulers. Farming indigo has now turned into a blessing, a way to change socio-economic status of hundreds of farmers in Rangpur.

Farmers of Rajendrapur of Sadar upazila are cultivating indigo and producing a dye from it, which they call 'True Bengal Natural Indigo Dye'. Punni Rani, an indigo farmer from Kumarpara, said, "I am a divorcee. Now I am leading a happy life with my daughter and two sons. Two years ago we couldn't make sure even two meals a day." Punni sold indigo leaves worth Tk 3,000 two months ago.

"I earned Tk 10,000 by selling indigo leaves to the company. Besides, I made Tk 5,000 from selling indigo sticks," said Jagadish Chandra Barmon, a landless farmer of Rajendrapur. He also cultivates indigo on the roadsides of his village. He added that since he was struggling for money, his daughter had to stop attending school after primary education. Those days are gone for him and she is back to school now.

Jagadish was referring to the Nijera Cottage and Village Industries Ltd (NCVI), a social enterprise of the underprivileged. It has helped change the socio-economic conditions of the underprivileged greatly. "That is not all. We have started exporting indigo to Canada, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and India," said Sumanta Kumar Barmon, chairman of NCVI.

With the increase in use of natural dye world wide, the demand for indigo dye is swelling. The company exported indigo dye worth Tk 10 lakh in the past six months. "Initially we weren't familiar with the export procedure. We have passed that stage and hopefully, the volume of export will double in a few months," added Sumanta.

Only 180 members started NCVI like a co-operative society. It has extended its working units and set up structures gradually. "It has grown into a company with about 1,500 shareholders from five northern districts," said Salma Begum, managing director of NCVI adding, "All shareholders are also workers of the company."

Farmers other than the landless are also cultivating indigo on their land. According to them, indigo crop on 25 decimals of land yields around Tk 3,000 in just three months. "Indigo stick is good fuel. We can make about Tk 4,000 more from selling the sticks," said Shawkat Hossain, a farmer of Rajendrapur.

CARE Bangladesh worked with the poor people of Rajendrapur under its Social Economic Transformation of the Ultra Poor (SETU) project. Shareholders of the company lauded the role of CARE for coming up with the idea of reviving indigo farming. Team leader of SETU project Anwarul Haq said, "When we found that the villagers needed to be involved with long term income generating activities, we began to explore resources for them. We found indigo farming to be a good solution to this end."

Anwar praised the company shareholders who have been working hard to upgrade it gradually. CARE Bangladesh provides technical support and training for the company. Some other cottage enterprises of the NCVI produce quality products, which are in high demand in the foreign countries.

The shareholders-cum-workers of the company manually sew elegant kantha (bedspread), which are dyed with indigo. Momotaz Begum, a director of the company, told The Daily Star that they participated in handicraft trade fairs in India on four occasions.

"Last August we joined a weeklong trade fair at Dasker in the Indian city of Bangalore. We had sales of Rs. 4 lakh," she said. At present the company has assets in cash and property worth Tk 2 crore. "We'll go for large scale production soon," added the company director (R. Sarkar, Daily Star, October 3, 2010).

Handloom products of Bengal as a whole has a good market in those countries provided these products are tinted with natural dyes, specially with vegetable ones. Incidentally, the primary ingredients for producing vegetable dyes are quite in abundance in W. Bengal and Bangladesh.. Climate and soil is most favourable for cultivating plants for producing vegetable dyes. Need of the hour is to revive the age-old technology of producing the vegetable dyes with the infusion of necessary upgradation.

Currently 8,000 tonnes of indigo are imported to Europe, 400 tonnes of which is natural indigo mainly from India. That share is expected to treble in the next ten years and new markets are being sought all the time.

Inkjet printers, for example, could use indigo pigment to complement environmentally friendly paper. Farmers and dye makers in tropical countries have more promising indigo-bearing plant species and should be able to compete. In music and mood, the expression 'the blues' means mournful and depressed. There is nothing depressed about the market for the natural colour blue!

Back to the Roots in Vegetable Dye Sari

Satranji : Weaving for a cause -Rugs steeped in historyIn 1972, about 5 crore people under poverty line -- rose to 7 crore in the year 2005

The projects, funded by the World Bank and other multinational donor agencies, have failed to achieve significant success in poverty reduction in the last 30 years in Bangladesh, speakers at roundtable observed yesterday. Terming all the World Bank projects in Bangladesh as 'mass destructive', they also said the bank should take the responsibility of the projects. They were speaking at the roundtable on 'World Bank in Bangladesh' held at the Jatiya Press Club in Dhaka. NGO Unnayan Onneshan organised the roundtable, moderated by Rashed Masud Titumir, chief of the NGO. The speakers also protested WB President Paul Wolfowitz's visit to Bangladesh. Wolfowitz is due in Dhaka today. They said the WB president would put pressure on the government to pass the immunity bill for WB-supported projects in the Jatiya Sansad (Daily Star,

However, the WB is not the main problem in development, observed M M Akash, professor of Economics Department of Dhaka University. "Basically, we create problems by extending our hands to the WB's activities," he added. With the same WB-aided projects, which made Bangladesh to close down jute mills, the government of India established three jute mills in West Bengal, Akash cited an example. "It will be impossible as well to attain millenium development goals (MDGs) if we follow projects of the donors." Those projects are neither homegrown nor prepared assessing people's needs, he said.

"However, we can avoid the donors' aids if we can stop making black money," said Abul Barakat, general secretary of Bangladesh Economic Association. In this country, some people are making around Tk 70,000 crore black money every year, he said (Daily Star, August 21, 2005).NGOs at a seminar in Dhaka yesterday observed that the country's poverty ratio increased in the last few years due to adoption of the World Bank and IMF prescriptions. They said in 1972, about 5 crore people were used to live under poverty line. But the figure rose to 7 crore in the year 2005, which resulted from adopting various suggestions made by these two international lending agencies, though aids from them increased by 63 percent during the same time. The observation came at a seminar on 'Interest of World Bank and International Monetary Fund: Policy Making, Condition and Sovereignty' organised by the Alliance for Economic Justice (AEJB), a platform of 36 organisations, including Campaign for Good Governance, at National Press Club.

"The government has failed to monitor the domestic market by following WB and IMF prescriptions. As a result, poor people suffer more due to sky rocketing prices of commodities," said Mousumi Biswash of the Campaign for Good Governance. She said, "By adopting WB and IMF prescriptions, about 2 crore people fall under poverty line during the last few years." Abdullah Al Mamun of Karmojibi Nari said," As the national budget and other economic policies are usually formulated by following the WB and IMF suggestions, the ratio of poverty alleviation has come down".

"If we continuously follow the donors' prescriptions instead of our own homegrown policy, it would not be possible to remove poverty from the country." Meanwhile, in protest against the intervention of WB and IMF, the AEJB has adopted some draft proposals, which would be publicised through a number of programmes. These programmes include seminars, submitting memoranda to deputy commissioners of 46 districts, lawmakers and finance minister, holding rally and forming human chain on September 16 in 46 districts, participating at Singapore summit and creating awareness through holding meeting there (Daily Star, September 12, 2006).

The story behind the headline was that Dukhimon Begum, a 40-year old mother of four from Durgapur Upazila of Rajshahi district had a quarrel with her rickshaw-puller husband, Manik Chand, because she bought a saree for her niece on the occasion of the latter's marriage. The family did not have any food to eat that night and the husband went to pull rickshaw next morning hungry. Faced with starvation, Dukhimon fed her two small daughters pesticide-laced biscuits and took some herself in order to be free from the misery. Little Moni, 6, and Mitu, 8, died, but the mother survived.

The Daily Prothom Alo (Bengali Daily Newspaper)of 18 September, 2004 published another report under the headline "Mother said, 'no food, eat poison'; the haughty girl did so." As the story goes, Motalab Matubbar of Hajikandi village of Madaripur district left home six months ago in search of work. His wife, Chandra Banu, has been supporting the family of two daughters and a son by working as a maid in neighbours' houses. During the recent incessant rain, Chandra Banu could not work and get any food for her children. In Shibchar Hospital, the mother told the newsmen that for the last two days she had no food to cook. Starving Rumana asked her for food. Frustrated, she told the girl to take poison. That night Rumana drank pesticide to take her life.

Bangladesh, predominantly an agricultural economy with a high population pressure of 834 residents occupied per square kilometres, has a population where most rural Bangladeshis are dependent on rice cultivation for survival. The farmers of this country are increasingly deprived of their rights to protect cultural and social heritage, genetic resource and unsustainable development programe are imposed on them.

The traditional wisdom that supported thousands of years of sustainable experience was extinguished and replaced by the wisdom from the North. Bengal's system of overflow irrigation in the 17th century ASD worked very well until the advent of the British. It not only enriched the soil, but also controlled maleria. According to Willcocks (1920), a British irrigation expert, riverwater in the early months of floods is gold. However, embankments have been constructed to inhibit fertile river water, fertiliser, pesticides and deep water wells. Hybrid seeds have been introduced since the 60's under the developing programme. Agarwal and Narain (1997) report:

In many villages where people had cared to maintain their traditional water systems, even after the arrival of piped water supply systems, there was no drinking water scarcity. But in villages that had neglected their traditional system, the drying up of the Rajasthan Canal had meant waterless pipes and hence an acute water crisis.Economic and social justice is a challenging task for all governments but it is specially so for the developing countries. If a country like Bangladesh did have the right leadership and politicians who did not keep them busy only with building their own fortunes, the prospect of the majority would not have come to a dead end. One of the reasons why the country has failed to live up to its expectation is the failure of the politicians to plan with its human resources. Investment in the population for fulfilling its needs and also contributing to the task of nation-building has been extremely low (Editorial; The Bangladesh Observer,October 4, 2004).

Last modified: October 3, 2010

Top of page

Back to Home Garden

Back to Women Culture

Back to Environment

Home