RAINFOREST DESTRUCTION

From the Himalayas to Bangladesh Coastal Plain

Since millions of years from the Himalayas to the dynamic coastal plain of Bengal was rich in panoramic vegetation and wild life. These tropical moist forests were botanically amongst the richest in the Indian sub-continent. The forests are most important as a repository of one of the world's richest of biodiversity. The last centuries were the dramatic events of destruction of these valuable resources of the earth. The origin of current crisis lies in the short-sighted forest policies initiated by the British, and even after independence, the same commercial outlook has remained the dominant theme within the forest departments. Unregulated commercial exploitation, big development projects and resulting poverty are the main reasons for deforestation. "Social Forestry Programme" has turned out to be little more than an extension of earlier forestry practices and it has failed to achieve its goal. Sunderbans, the largest mangrove forests of the world, was once covered all along the coastal plain of Bangladesh. Had it been maintained, the Bay of Bengal would have turned into one of the largest fish grounds of the world, gained land one third to the present size of Bangladesh, and have protected millions of lives during cyclone storms. The problems of deforestation is mainly political and it can be solved, if poverty focused projects contain the attitude of "by the people and for the people" participation

About 35 million years ago the modern Himalayan mountains began forming and the sediments were actively shed off south of Dinajpur (north Bengal) and Shillong plateau and continued to deposit about 16-18 kilometres of alternate deposit of sand, silt, clay and plant remains. The rich deposit of natural hydrocarbons and coal deposits in Assam and Bangladesh owe its origin mainly from once rich vegetation. The geological formation of Bangladesh since 10.5 million years is characterised by river dominated and tidally influenced delta-front. Bangladesh, an important transition zone between Indo-China, the Himalayan and rest of the Indian- subcontinent was once rich in wild vegetation and wildlife species

These forests shaded many smaller streams, provided leaves fall that contributed organic matter of a specific chemical composition to the stream, broke the force of rainfall and decreased run-off. On the other hand, these tropical moist forests were botanically amongst the richest in the sub-continent, and there were also diversity of mammals and a high diversity of birds, and ecosystems. But, forests and grasslands have retreated massively before the expansion of settled agriculture, and nowhere more dramatically than in Indian-subcontinent, where step-by-step between 1770s and 1850s, Britain established its raj, or imperial regime (Tucker, 1988). A recent study, which covers most of the subcontinent, shows that the years between 1890 and 1970, more than thirty million hectares of land were transformed from forest and grassland into areas of crop production and settlement; the amount of land being cultivated rose over 45 per cent. In the same years the population grew 147 per cent.

The panorama of forests constitutes mangrove forests in the coastal region, evergreen tropical forests from Andaman to eastern Burma, Chittagong Hilltracts and Assam, to dry alpine scrub high in the Himalayas in the north. Between the two extremes, the region has semi-evergreen rain forests, deciduous monsoon forests, thorn forests, subtropical broad-leaved and subtropical pine forests in the lower montane zone and temperate montane forests (Lal, 1989).

Most of Bangladesh was originally forested, with coastal mangroves backed by swamp forests and a broad plain of tropical moist deciduous forest (IUCN, 1987). However, most of the original vegetation has been cleared. The hills of Chittagong and Syleht were once covered by tropical evergreen and semi-evergreen rain forests ( FAO/UNEP, 1981). Remnants of these forests are found in the eastern part of the country.

Tropical monsoon forests are known as Sal (Shorea robusta) is almost removed. Relics may be found in the Dhaka, Tangail and Mymensingh Forest Division. Tidal mangrove forest is located in the Sunderbans with small area in Chittagong district. Bangladesh once forested with such rich vegetation is now almost completely deforested. Less than five percent of the original cover remains.

In 1950 Nepal possessed 55% of forested area, in 1982 it declines to 25%, and according to the Government of Nepal and the World Bank at the end of this century Nepal will lose most part of its forest reserve (Gizycki, 1987). The recent human interference may be prolonging and intensifying the dry spells natural to climate. In India a study of vegetation and rainfall records over 100 years has shown that deforestation tends to be accompanied by both lower rainfall and fewer rainy days. India's Kabani Project, for example, created a 2500-hectare to provide a reservoir but also led to deforestation of 12,500 hectares to provide space in which displaced villagers could be resettled. As a result, rainfall dropped 25 per cent from 1500 to 1125 millimetres a year (Jay, 1985).

Deforestation in the Indian sub-continent has caused severe ecological damage and brought untold misery. A number of tropical crops are more vulnerable to climate than is usually the case with temperate-zone crops; in humid tropic a marginal shortfall in precipitation can cause substantial shortfall in the outputs of several staple crops (Oram, 1986). Mener-Homji (1985) has shown in India that decrease of rainfall with the increase rate of deforestation from 1886 to 1982. The origin of current crisis lies in the shortsighted forest policies initiated by the British. Although the rural people had been using forest resources for centuries with success, the British Government introduced organized forest management under revenue forests. Throughout the imperial era the British administered two-thirds of the Indian-Subcontinent directly but left the remaining third under the autonomous rule over five hundred indigenous aristocratic houses, the "Native Princes". Within this framework an intricate system of administration and economic change evolved, so varied that almost any generalisation about India, as a whole in that era is nearly foolhardy. But one theme stands out in the subcontinent's history: the steady expansion of land under the plough, at the expense forest and grassland (Tucker et al., 1983).

The rapid deterioration of the forest stocks in the Indian Subcontinent during the last century can be traced both to the reservation for large forest areas for monopolistic use of the British Government. The origin of the current crisis lies in the shortsighted forest policies initiated by them. The only interest that the former colonial rulers had in the forests of India was in their revenue earning capacity (Hayter, 1989). The reservation of the forest resulted in the eviction of the tribal from the forest areas, thus denying them their main source of livelihood. There are forty-four million adivasis, or so-called tribal in India, who are outside the cast system and most of them depend on the forest for their livelihood. According to church reports about 185,000 native tribal in Bangladesh are killed by the government forces (Behrend et al., 1990). The evolution of this tragedy has been inseparable from the erosion of tribal life in the hills.

Unfortunately, even after independence, the same commercial outlook has remained the most dominant theme within the forest departments. The colonial requirements for timber for ships, and later for railway sleepers and pit props, have been succeeded by a vast requirement for pulpwood. At present India's consumption of paper is only 2 kg. Per person per year, compared to 268 kg in the USA. But its pulpmills are severely short of raw materials and operating below capacity. They have destroyed many of their sources of supply, especially bamboo, through over-exploitation.

Figures published in 1984, based on satellite imagery, showed that 1.3 million hectares of forest disappeared between 1972 and 1975 and from 1980 to 1982. Shifting agriculture is one of the most important factors in the conversion of the country's forest vegetation. It is widely practised in the northeastern states of India (Aarunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Tripura). Where it is legally recognised as an acceptable form of land use. Large areas of reserve forest have been released for permanent agricultural settlement since the Second World War. The lush green valleys of Himachal Pradesh are rapidly degrading with no sign of vegetation. V. Malhotra (1992) describes

More and more areas of State are becoming fuel, fodder and water scarcity ridden. Cash crops have further deteriorated the health of the Himalayas. Rains have decreased and snowfall is becoming a legend in the Himachal hills. The forestland is being used for the cultivation of crops and this is creating imbalance in the ecological system. The enormous quantity of tree felling has increased soil erosion. The fertility of the soils has been decreased day by day. The depletion of forests in and around Una, Kangra, Simla, Bilaspur, Solan etc. are the indices of deforestation. The queen of hills is being stripped of her clothes...The new techniques in the horticulture industry brought revolution in the apple output but the wood required to manufacture apple boxes has adversely affected forest resources. Small timber retailers and saw mill operators turned into forest Mafia and became millionaires overnight... The changing climatic patterns, decreasing rain, scattered snowfall and increasing soil erosion have further worsened their economic plight.The rainy forest of eastern Himalayas is one of the richest of the world. The number of plant species has been estimated at 9 000 or more (Stone, 1992). The long history of human occupation and survival in the Himalayas did not cause too many drastic changes in this delicate mountain ecosystem until very recently. Mass wasting (process through which large masses of earth material move downhill under gravity) are due to natural and anthrogenic factors. Among the most anthropogenic factors in all parts of the Himalayas are :

Loss of forest cover Extension of agriculture onto steep slope Open-cast mining without environmental control Roads built without regard for geological factors. The mountainous states of Sikim, eastern Himalayas, are also exposed to accelerating environmental changes. Extension of plantation agriculture, building up hydroelectric power stations, laying out new roads and buildings - all these activities are taking place at the cost of depleted forests and defaced slopes. Landslides, erosion of soil, change in climatic and hydrological regimes, flood, erratic rivers, sandy and gravely riverbeds were the natural consequences. Everywhere the land and the forests have suffered most (Chakravarti, 1992).

The environmental impact due to mining in the Himalayan region (Utter Pradesh - 4819 ha, J & K state 886 ha, West Bengal 11471 ha) includes loss of production (forest, agriculture, pasture), loss of top soil, reduction in flow of water, lowering of water tables, hazard of debris, sedimentation of streams, and fire hazards etc. (Sahni, 1992).

Between 1951 and 1976 agricultural land increased by 430,000 sq. km (15 percent of land area), much of this through conversion of non-reserve forests, which were originally intended to meet rural fodder, fuel and timber supply. Certain groups of plants are particularly at risk notably medical plants due to over-exploitation by the local pharmaceutical industries (Hussain, 1983).

Now it is realised that the forest products are in short supply and the ecological changes are causing human suffering (Shyamsunder et al., 1987). The construction of dams and implemented irrigation systems raise an increase of incidence of vector-borne and water related diseases.

Dams are built on river running through the most fertile forestlands. Between 1947 and 1957 about half a million hectares of forest were lost due to major river projects (Centre of Science and Environment, 1982). About 49500 hectares forest has perished in India from 1950 to 1975 after the completion of water reservoir projects. The plans have a commercial and industrial bias and have indifference to human and ecological concerns and have no space for the right of indigenous peoples who have lived in tropical forests since time immemorial. The sufferings of poor people is continued to be endless, for example, the Armada valley Project - the massive series of big dams built and planned in the Armada valley have also destroyed, or threaten to destroy, forests. Many thousands of people are being displaced; ultimately more than a million may have their land and villages flooded.

Deforestation in the catchment areas of India's dams and reservoirs is a major problem because it has led widespread siltation several times faster than those projected at the time of their construction. Many new constructions of dams are in plan and it is expected that many million of hectares of land will be lost through submergence and clearance for irrigated agriculture.

Another example of destruction of most valuable item for house construction is bamboo in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh a large quantity of bricks are produced for building, road constructions etc., and these are produced at the cost of fertile soil and a huge amount of irreplaceable urban forest resources. All types of valuable trees such as fresh roots of the bamboo, which are invaluable for the reproduction, are ruthlessly burnt for brick production. In many areas these are the only source of cash money for the landless and poor farmers. It requires about 28 metric tonnes of wood to produce about 100,000 bricks. Another example of destruction of the mangrove forests is the production of safety match boxes and sticks for the ignition of fire. During 1987-88 Bangladesh produced about 13,754000 large matchboxes, and this could have been reduced, if the Bangladesh Government had allowed a few lighter producing plants, which could have used a part of the country's existing hydrocarbon reserve. But the match industries have a strong lobby in the Government; they do not only destroy forests but also create extremely polluted effluents during production

A major source of forest destruction is the spontaneous colonisation, which often follows the building of roads. In Nepal, the British provided aid to build roads, which had primarily military-strategic aims. The Overseas Development Group at the University of East Anglia reports on the effects of roads in the west central Nepal that when roads are built into forests, they cause destruction not only directly but also by providing access for new settlers who may destroy large additional areas of forest. Both the forests and the people living within them suffer.

The Kosi Hills area is in a band of hills, which stretches across Nepal between the plains (terai) in the south and the high Himalayas in the north. The hills are densely populated, mostly with small subsistence farmers, who cultivate steep hillsides wherever cultivation is marginally possible. Many landholdings are extremely small, there is considerable poverty, and serious deforestation has caused or aggravated erosion and landslides (Hayter, 1989). Many think that the loss of tree cover in the Himalayas, especially in Nepal, which moderated the flow of water, has contributed to floods in Bangladesh.Forests are a key to flood control, but if the atmosphere continues to be loaded with oxides of nitrogen and sulphur by the growing pollutant producing industries and automobiles, that ecosystem service may be ultimately lost. The waste disposal and nutrient recycling services of ecosystems, and their provision of food from fresh water, may also be comprised if atmospheric influences lead to increased acidity of soils, lakes, and streams. The ability of ecosystems to provide pollination and pest control services and to maintain nature's vast "genetic library" can be reduced. The sub-continent is at present anticipating this problem by removing trees and increasing atmospheric pollution.

Forests were nationalised by the government of Nepal in 1956 in an attempt to protect them, paradoxically, this is now considered a major factor in their destruction. The prospect of nationalisation led to attempts to lay claim to land by cutting down or burning trees, since state land was defined as land on which there were trees, and to the abandonment of traditional conservation practices

Under the Integrated Rural Development Programme of the late '70s (IRDP) two types of forests "panchayt forest" and "panchayt protected forest" was carried out by many aid-giving agencies. Like most of the other aid agencies involved in IRDPs in Nepal, the British seem to have a project that was not a success. J. Stewert of Oxford Forestry Institute UK describes in the Commonwealth Forest Review (1984):

The villagers also well understood the physical consequences of deforestation that are visible all over Nepal: the vicious circle of increased run-off resulting in springs drying up, soil loss, gullies and landslides, and resulting inexorable loss of productivity of the land, forcing cultivation even more steep, marginal and unstable slopes, and further deforestation.The "Arun 111" hydro electric project requires diverting river through a hole drilled in a mountain so that water can reach generators. And a long road to be built into the valleys that have adverse environmental and social impacts, including extensive deforestation. The Arun Concern Group believes that the 122-kilometre road will go through a remote, biologically diverse mountain valley containing one of the few pristine forests left in the Himalayan range.

On the eastern fringe of the Himalayan ranges, where the Brahmaputra River has its great arc to the Southwest toward the Bay of Bengal, Assam's dense forest belt has been under siege since the early nineteenth century. By 1900 Assam's 55,156 square miles included 20,830 square miles under government forest control, one of the highest percentages of any state in India. The history of Assam's forests has been intertwined with the intricate ethnic and cultural pattern of the state (Gate, 1926). The remote high hills of Assam and adjacent regions are home to a wide variety of tribal groups, whose subsistence has been based primarily on shifting agriculture (Chaturvedi et al., 1953). Until recently tribal populations were thin enough that they presented no fatal threat to mixed forests, if left to them. The sophistication of the indigenous strategies is not apparent since they are not recorded in paper. In the attempt to understand the prospects and constraints for sustainable development, this heritage of local environmental wisdom should not be ignored.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century most of the peasants from the low land began surging into the fertile Assamese fertile land. The same trend has been evolved in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, now Bangladesh

The other cause of transformation, one that quickly penetrated far into the hills, was the tea industry. The tea plantations of Northeast India are the classic example of a foreign-dominated plantation economy, which controlled a dependency's land-use patterns and was highly sensitive to markets in the industrialised world (Tucker, 1988). After, 1833, when the East India Company's new charter allowed foreigners to own rural land in India, European tea planters quickly bought large tracts of hill land in Assam and north Bengal. Most tea plantations were established by clearing natural forests. Whenever markets for tea were strong enough to enable expansion of plantation acreage, forest cover was correspondingly reduced.World War II brought major changes in forest production. Between 1939 and 1945 timber production in the reserves more than doubled, while fuelwood cutting there more than tripled. The height of this pressure came after 1942, when heavy concentrations of troops moved up Brahmaputra valley. The war made major changes in forestry technology, not only in Assam but also throughout the Himalayan region, for the war effort required new motor roads and rail lines. The motorization of forestry was a turning point in the mobility in timber exports and settlements. Aftermath independence the political and ethnic turmoil in this region led to similar, but more intensive conflicts in recent years, on a steadily shrinking base of land and vegetation.

In the lower reaches of the Brahmaputra, on the rich alluvium plains stand forests of the great hardwood Sal (Shorea robusta), the easternmost extension of the great sub-Himalayan sal belt. Because of the perennially warm, moist climate of lower Assam, these are the finest quality of all sal stands. The combined interests of planters, imported labourers, and immigrant farmers placed a heavy escalating pressure on the forests of Assam. In twenty years ending in 1950 the immigrants turned some 1,508,000 acres of forest into settled agriculture. In the sal forests near Tangail, Bangladesh, forest cover was reduced from 20,000 acres in 1970 to 1,000 acres in 1990, due to illegal felling (Ministry of environment and Forest, Govt. of Bangladesh, 1991

The Sunderbans is the largest compact mangrove forest of the world, located in the estury of the Ganges covering an area of about one million hectares in soth-west of Bangladesh and south eastern state of West Bengal in India.

The mangrove forests of Bangladesh and India are vital suppliers of oxygen, food source of coastal and offshore fishers, wildlife, rare fauna and flora, micro-organism, essential elements to the onshore shrimp cultivation, they protect from severe coastal storms and accelerate land reclamation.

UN had rightly put the theme of this year's World Environment Day 'Forests: Nature at Your Services' to highlight the importance of different services of forests, including the ecological ones, to mankind. This write-up intends to elucidate the ecological services provided by the Sundarbans, the world's largest single tract mangroves, on an area of 10,029 sq km between India and Bangladesh, to find their monetary value for promoting better understanding of the need of its conservation in real sense.

Aquatic and terrestrial species: Biological resources are a natural power-house. The Sundarbans, a forest ecosystem full of life, energy and enthusiasm, provides habitats for about 6540 species, both aquatic and terrestrial. About 5,700 species are of vascular plants and 840 species belong to the forest wildlife (Akhond, 1999). The mangrove wildlife habitats provide both food and shelter to organisms. For some species, especially plants, a particular mangrove may provide every element required to complete their life cycle. Other species depend on the mangrove area for part of a more complex life cycle. Many aquatic animals such as fish and prawn depend on mangrove areas for spawning and juvenile development. Many species of migratory birds depend on mangroves for part of their life cycle like resting or feeding while on migration. The microorganisms eat the mangrove's leaf litter, and in turn are eaten by juvenile fish and shrimp (The Shedd, 2011). The mangrove forests, thus, facilitate the continuation of life cycle of innumerable organisms which greatly contributes to keep ecological equilibrium Biomass and productivity: In an ecosystem, biomass represents the base of food chain. The standing stock of mangrove plant biomass combined with nutrients, water, and light maintains the existing biomass, grow new biomass, and support the rest of the food chain. Plant biomass is also important as a structural, abiotic feature in the landscape. It can perform physical as well as biological functions, like trapping sediments and serving as nesting sites for animals.

Erosion control: In the first place, the mangroves in Sundarbans contribute to limiting erosion of soil. The land of mangrove ecosystem is moulded by tidal action, developing a distinctive physiography. An intricate network of interconnecting waterways run in a generally north-south direction, intersecting the whole area. The water which enters the forests from upstream can easily run downstream without making extreme pressure on forest terrestrial part.

Climate regulation: The importance of forests stretches far beyond their own boundaries. The forest plays a vital role in the battle of halting climate change induced damage because they store nearly 300 billion tons of carbon in their living parts -- roughly 40 times the annual greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels (Green Peace International, 2011). Mangroves is pioneering forest type that acts as giant carbon storage. According to the study conducted by Donato, D. C. et al. in 2011, mangroves are among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics, containing on average 1,023?Mg carbon per hectare. Taking this datum into account, the total carbon storage of Bangladesh Sundarbans stands at about 615.5391 million Mg.

Protective role: Mangroves plays a great part in shoreline stabilization. This is achieved through the binding and cohering of soil by plant roots and deposited vegetative matter, the dissipation of erosion forces such as wave and wind energy, and the trapping of sediments. Thus the intricate root system not only protects the shoreline from erosion but also adds land. The mangroves reduce the intensity of cyclone and tidal surge acting as a natural barrier for the coastal human habitations. After the super cyclone Sidr, the protective role of the Sundarbans was widely felt. It is commonly assumed that the damage from cyclone Sidr and Aila would be many times higher without the Sundarbans.

Sediment and nutrient retention: The physical properties of mangroves like vegetation and water depth tend to slow down the flow of water. This facilitates sediment deposition. The sediment retention function of mangroves may have two important effects. Firstly, it may lead to accretion of arable land within mangrove areas. Secondly, it may protect downstream economic activities and property from sedimentation. Thirdly, it may accomplish beneficial removal of toxicants and nutrients since these substances are often bound to sediment particles. Sediments trapped by roots prevent silting of neighbouring habitats.

Nutrient cycling: Nutrient loading, a common type of pollutant in the air, water, and soil can influence organisms in many different ways, from altering the rate of plant growth to changing reproduction patterns in certain extreme situations, leading to extinction. Organic nutrients, including those from humans and animal waste, are often trapped by mangroves. Micro-organisms in soil and on roots also remove toxins and nutrients, providing another natural filter in the mangrove muck. Nutrients are often associated with sediments and therefore can be deposited at the same time.

The value of nutrient cycling function of mangroves will be obvious to us if we replace this function with the cost of waste treatment operation (Bann, 1998).

Water regulation: Mangroves help accomplish both recharge and discharge of ground water. Water moves from the mangroves to an aquifer that can remain as part of the shallow groundwater system and may supply water to surrounding areas to sustain the water table, or it may eventually move into the deep groundwater system, providing a long term water resource. This is of cracking value to communities and industries that rely on medium or deep wells as a source of water.

Ecological services: For recognizing the ecological services of forests, particularly mangrove forests, efforts have hardly been made even at the global level let alone at the national and individual ecosystem level. Although United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has undertaken a large project entitled “The Economics of Ecosystem and Biodiversity (TEEB)” in 2007 to value overall services of different natural ecosystems, till today it has succeeded to evaluate services of a few ecosystems not on regional but on global scale.

However, an attempt has been made here to determine the annual economic value of the ecological services of Bangladesh Sundarbans using the forest services valuing rates calculated by Costanza in 1997 and accordingly the total value of the ecological services of Bangladesh Sundarbans stands at about USD 379.67 million.

The Sundarbans is one of the most biologically productive natural ecosystems.In the face of numerous challenges, both nature and human induced, it has been more than imperative to determine its total contribution to the well-being of society in terms of economy, ecology and culture with the aim of raising awareness of all concerned including local stakeholders regarding how worthy the mangrove forest is to us.

Accordingly, valuing ecological services of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh is a demand of the hour. This is International Year of forests. It is a unique opportunity to boost understanding of the mangrove ecosystem in Bangladesh: To disseminate information and to promote its restoration and conservation campaign finding the monetary value of all the services including the ecological ones that the forest provides on continuous basis.

The ancient Suderbans extended all over the coastal plain and river dominated delta-plain. One of the most illustrated tropical ecosystems of the world is threatened to extinct. The mangrove ecosystem is linked upstream with the land and downstream with the sea. The organic matter that the mangrove ecosystem produced through complex detrital based food web represents a major source of food for a variety of marine and brackish organisms. This area is considered to be one of the most productive zones of fisheries of the world. More than 475 species of fish belonging to 133 families about 10 species of marine shrimps are of commercial importance, about 108 species of shellfish, molluscs, crabs and two species of lobster from the Bay of Bengal are recorded.

The unique vegetation of Sunderbans is classified under three zones: freshwater forest (north eastern part), moderately saltwater forest (eastern part) and saline forest (western part). The forest became poorer and more open as one proceeds towards the sea or towards the west (India). The fresh water zone in the north is generally most productive with good quality sundri, gewa, passur, kranka and other timber species flourishing. But with the increase of salinity the mangrove ecosystem has been seriously affected after the construction of the Farakka dam in India. The abnormal reduction of the Ganges flows during dry period have caused excessive siltation, elevation of the bed level sand consequent reduction of flood water discharging capacity of the channels, shifting of Ganges flows thereby blockage of the Gorai river off take.

Besides the Sunderbans is dissected in the north south by numerous rivers and streams, which are, or were, distributaries of the Ganges and form the five estuaries opening into the Bay of Bengal. But today only the Passur and Baleswar rivers with their respective distributaries have a direct connection to the Ganges, and thus to an uninterrupted source of fresh water (BCAS, 1990). Higher salinity than usual was observed as early as 1976 when the Khulna Newsprint Mills found river water too salty to use during the dry period. Recent studies at Free University Berlin, Germany confirmed that during the dry period, in the rivers southwest of Bangladesh low surface water level favours intrusion of surface water salinity from the Bay of Bengal higher than previous records (Hassan, 1992The unique vegetation of Sunderbans is classified under three zones:. The forest became poorer and more open as one proceeds towards the sea or towards the west (India).freshwater forest(north eastern part), moderately saltwater forest (eastern part) andsaline forest (western part)

The fresh water zone in the north is generally most productive with good quality sundri, gewa, passur, kranka and other timber species flourishing. But with the increase of salinity the mangrove ecosystem has been seriously affected after the construction of the Farakka dam in India. The abnormal reduction of the Ganges flows during dry period have caused excessive siltation, elevation of the bed level sand consequent reduction of flood water discharging capacity of the channels, shifting of Ganges flows thereby blockage of the Gorai river off take. Besides the Sunderbans is dissected in the north south by numerous rivers and streams, which are, or were, distributaries of the Ganges and form the five estuaries opening into the Bay of Bengal. But today only the Passur and Baleswar rivers with their respective distributaries have a direct connection to the Ganges, and thus to an uninterrupted source of fresh water (BCAS, 1990). Higher salinity than usual was observed as early as 1976 when the Khulna Newsprint Mills found river water too salty to use during the dry period. A study at Free University Berlin, Germany confirmed that during the dry period, in the rivers southwest of Bangladesh low surface water level favours intrusion of surface water salinity from the Bay of Bengal higher than previous records (Hassan, 1992).Mangroves are located in estuarine areas and provide important habitats for fish e.g. nursery functions, shelter for juveniles and food for piscivorous species.

The extent of dependence may differ between different species e.g. most species of Mugilidae found in sheltered estuaries or mangroves seldom occur in coastal waters. In addition, tropical clupeoids are estuarine dependent as juveniles. Others such as Asian Tenualosa (ilish) are estuarine dependent with reference to spawning grounds. It is noted that predatory action of some larger fish are hampered due to mangrove structure although some individuals did penetrate these systems in search for food.Mangroves play a nursery role for estuarine fishes. The mangrove forests are important for healthy coastal ecosystems because the forest detritus, consisting mainly of fallen leaves and branches from the mangroves, provides nutrients for the marine environment. These detritus support varieties of sea life in complex food webs associated directly through detritus or indirectly through the planktonic and epiphytic algal food chains. The plankton and the benthic algae are primary sources of carbon in the mangrove ecosystem, in addition to detritus. The shallow intertidal reaches where there is mangrove wetland provides refuge and nursery grounds for juvenile fish, crabs, shrimp and molluscs. The reasons for these dependencies may be described as follows:

The trophic resources (e.g. convergence of riverine freshwater and tidal currents) produce large volumes of turbid water where organic particles and fragments are concentrated and subjected to strong microbial activity to release nutrients. The nutrient released is used by phytoplankton, at the base of a web including zooplankton and shrimps. Abundant food resources are thus made available to fish and shrimp post-larvae, with a range of planktonic food sizes matching their filtration and capture capabilities.

Water turbidity and shade (e.g. turbidity and shade provided by the mangrove leaves and pneumatophores) reduce the perception distance of predators and increase the escape rate and consequently the survival rate of young fish and shrimps. Estuaries and mangroves are places where less fish predation occurs due to turbid water, absence of larger fish, shallow water and increased hiding places for juveniles in sea grasses or mangrove branch, roots, and pneumatophores.

Structural diversity (e.g. diversity and structural complexity of mangroves and estuaries) offers trophic niches for different species and sizes. The higher concentration of food present in pneumatophore areas supports abundant fish species.

Fish depend on mangroves and estuaries as nurseries (food and shelter) and that these habitats are important for juvenile and adult fish for their survival and growth. Hambrey, (1999) reported that economic valuation of the fisheries function of mangroves was estimated to range from US$ 66 to almost $3000/ha. Therefore, the worldwide estimates of the value of the mangroves to commercial fisheries have raised awareness about importance of mangroves. So the Sundarbans mangrove forest needs proper attention, management and political commitment for sustainable coastal fisheries development in the area.

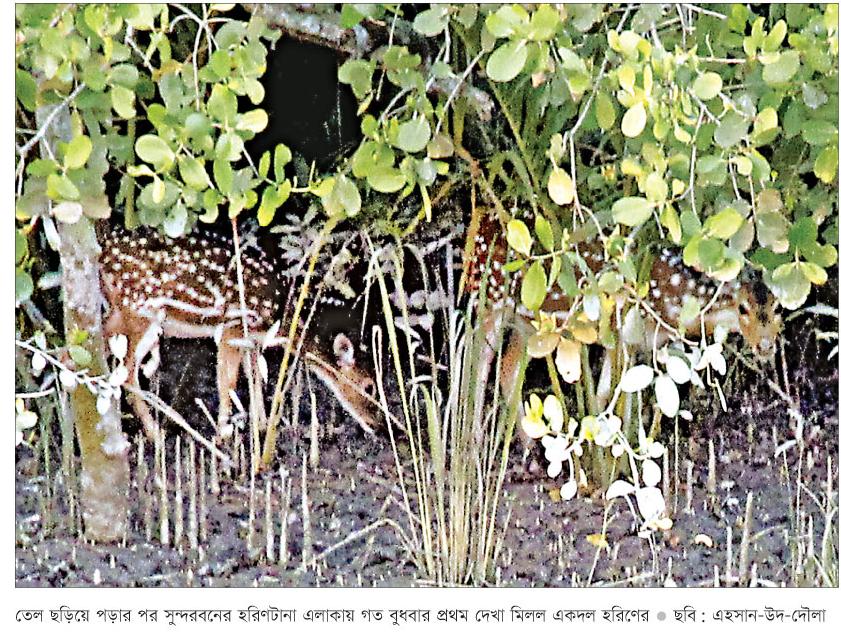

375 species of wild animals and birds in Bangladesh part of the Sundarbans

Oct 13, 2004 : At present there are 375 species of wild animals and birds in Bangladesh part of the Sundarbans, the largest mangrove forest in the world. M Tariqul Islam, DFO of Sundarbans East Division, said different surveys conducted in different times in the world's largest mangrove revealed the figure. Royal Bengal Tiger, deer, monkey, crocodile, turtle, boar, dolphin, fish-eating aquatic animal (Udbiral) and different types of snake are among the wild animal.

According to the survey, there are 419 Royal Bengal Tigers, over 1.20 lakh deer, 40,000 monkeys, 25,000 boars, 1,500 crocodiles and 2,500 fish-eating aquatic animals in Bangladesh part of the Sundarbans.

The ODA (Overseas Developing Agency, UK) inventor carried out a survey in 1983, indicating that the standing volume of sundari and gewa has declined 40 to 45 per cent respectively since the previous inventory in 1958-59. Besides the wild life is in danger - eighteen species of animals are reported to have been lost in this century, 130 are endangered, and there are also over three hundred species listed as rare and doubtful of occurrence. The ODA did not get further involved in mangrove forest protection project due to lack of Bangladesh Government's integrity and sincerity for such projects (Hayter, 1989).

At present Sunderbans with all its exotic flora and fauna is in an alarming situation due to disruption of the natural flow of the river water, increase in salinity, unplanned shrimp culture, overcutting and an overestimation of rate of regeneration, mismanagement and corruption, and an increase in pollution by disposing ballast water, oil spills, bilge-water, shipbreaking operation, untreated chemical and industrial waste (Anwar, 1990).

Dams/Barrages Relation to Recent Arsenic Poisoning

Salinity, sea level rise threaten Sundarbans

Natural resources of the Sundarbans, especially various kinds of trees, are seriously threatened due to the rise of sea level and salinity caused by climate change. The low areas of the world's largest mangrove forest, declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO, are flooded by tidal waters every year due to rise of sea level and excessive silt deposit that cause diseases and deaths to various kinds of trees. Many diseases, including 'Agamora' (top dying), affect different species of plants and trees, including the Sundari tree, in the Satkhira Range of the Sundarbans.

Abdur Rahman, a teacher of Khulna University along with some researchers of the forest department, has been conducting a joint research on the death of the trees in the forest (Source: The Financial Express, March 03 2007).

As the forest department has not yet taken any preventive measures to save the trees and plants, the diseases have been spreading, causing many species of valuable trees to die.

Besides, rising salinity in rivers, canals and other water bodies in the mangrove forest, was also one of the reasons for the death of trees.

Sources at the forest department research centre said the quantum of salinity in the rivers and canals in the Satkhira Range of the Sundarbans is 27-33 PPT against the accepted level of 5-10 PPT. While visiting different areas of the forest, this correspondent found a wide variety of trees, including Sundari, Poshur, Keowa, Geowa, Bain, Garan, Garjan, Dhundol, Fakra, Hental, Bet, Jhau and Hogla, affected by 'Agamora' (top dying) disease, causing death to many trees while many became reddish.

Not only the trees and plants, but also many species of animals and birds have been facing extinction due to salinity on the ground. The concerned departments of the government, however, have not taken any action to protect the bio-diversity of the forest. A forest research station was established in 1994 in Munshiganj of Shyamnagar Upazila, adjacent to the Sundarbans, with one station office having one nursery supervisor, one guard and two boatmen. But what research activities the station was engaged in could not be ascertained.

Kadamtala station officer of Satkhira Range M Golam Mostafa said that as a preventive measure, the concerned section of the forest department cut trees affected by 'Agamora' (top dying) disease as a means to protect the adjoining trees.

As there were some irregularities over the sale of the diseased trees through auction, the government banned cutting of the affected trees in 1995, he said.

The specific reasons of the widespread top-dying disease of Sundari trees in the Sundarbans mangrove is Farakka Barrage largely responsible for the disease, saying increase of salinity in soil, reduction of normal flow of water and ecological disorder are causing the disease (The experts concerned to find out the specific reasons of the widespread top-dying disease of Sundari trees in the Sundarbans mangrove, Holiday, September 23, 2005).

Sundarbans

The Sundarbans, Shundorbôn) is a natural region in Bengal. It is the largest single block of tidal halophytic mangrove forest in the world. The Sundarbans covers approximately 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) of which 60 percent is in Bangladesh with the remainder in India. The Sundarbans is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sundarban is the world biggest mangrove forest. In Bangladesh tourism, Sundarban plays the most vital role. A large number of foreigners come to Bangladesh every year only to visit this unique mangrove forest. Besides, local tourists also go to visit Sundarban every year. The area of great Sundarban is approximately 6000 sq. km.

AREA: Nearly 2400 sq. miles or 6000 sq. km. FOREST LIMITS: North-Bagerhat, Khulna and Sathkira districts : South-Bay of Bengal; East-Baleswar (or Haringhata) river, Perojpur, Barisal district, and West-Raimangal and Hariabhanga rivers which partially form Bangladesh boundary with West Bengal in India.

MAIN ATTRACTIONS:

Wildlife photography including photography of the famous Royal Bengal Tiger, wildlife viewing, boating inside the forest will call recordings, nature study, meeting fishermen, wood-cutters and honey-collectors, peace and tranquility in the wilderness, seeing the world's largest mangrove forest and the revering beauty. The Sundarbans are the largest littoral mangrove belt in the world, stretching 80km (50mi) into the Bangladeshi hinterland from the coast. The forests aren't just mangrove swamps though; they include some of the last remaining stands of the mighty jungles, which once covered the Gangetic plain.

The Sundarbans cover an area of 38,500 sq km, of which about one-third is covered in water. Since 1966 the Sundarbans have been a wildlife sanctuary, and it is estimated that there are now 400 Royal Bengal tigers and about 30,000 spotted deer in the area.

Sundarbans is home to many different species of birds, mammals, insects, reptiles and fishes. Over 120 species of fish and over 260 species of birds have been recorded in the Sundarbans. The Gangetic River Dolphin (Platanista gangeticus) is common in the rivers. No less than 50 species of reptiles and eight species of amphibians are known to occur. The Sundarbans now support the only population of the Estuarine, or Salt-Water Crocodile (Crocodiles paresis) in Bangladesh, and that population is estimated at less than two hundred individuals.

With the approach of the evening herds of deer make for the darking glades where boisterous monkeys shower Keora leaves from above for sumptuous meal for the former. For the botanist, the lover of nature, the poet and the painter this land provides a variety of wonder for which they all crave It's beauty lies in its unique natural surrounding. Thousands of meandering streams, creeks, rivers and estuaries have enhanced its charm. Sundarbans meaning beautiful forest is the natural habitat of the world famous Royal Bengal Tiger, spotted deer, crocodiles, jungle fowl, wild boar, lizards, theses monkey and an innumerable variety of beautiful birds. Migratory flock of Siberian ducks flying over thousands of sail boats loaded with timber, golpatta (round-leaf), fuel wood, honey, shell and fish further add to the serene natural beauty of the Sundarbans.

Means of Communication: Water transport is the only means of communication for visiting the Sundarbans from Khulna or Mongla Port. Private motor launch, speedboats, country boats as well as mechanized vessel of Mongla Port Authority might be hired for the purpose. From Dhaka visitors may travel by air, road or rocket steamer to Khulna - the gateway to the Sundarbans. Most pleasant journey from Dhaka to Khulna is by Paddle Steamer, Rocket presenting a picturesque panorama of rural Bangladesh. Day and nightlong coach services by road are also available. The quickest mode is by air from Dhaka to Jessore and then to Khulna by road. Journey time: It varies depending on tides against or in favor in the river. Usually it takes 6 to 10 hours journey by motor vessel from Mongla to Hiron Point or Katka.

FAMOUS SPOTS: The main tourist spots in Sundarban are Karamjol, Katka, Kochikhali, Hiron point and Mandarbaria. Hiron Point (Nilkamal) for tiger, deer, monkey, crocodiles, birds and natural beauty. Katka for deer, tiger, crocodiles, varieties of birds and monkey, morning and evening symphony of wild fowls. Vast expanse of grassy meadows running from Katka to Kachikhali (Tiger Point) provides opportunities for wild tracking. Tin Kona Island for tiger and deer. Dublar Char (Island) for fishermen. It is a beautiful island where herds of spotted deer are often seen to graze.

Katka: Katka is one of Heritage sites in Sundarban. In Katka there is a wooden watching tower of 40 ft. high from where you can enjoy the scenic beauty of Sundarban. A beautiful sea beach is there is Katka; you will enjoy while you are walking to go the beach from the watching tower. Verities birds are visible in Katka.

Hiran point: This is another tourist spot in Sundarban. It is called the world heritage state. You can enjoy the beauty of wild nature and dotted dears walking and running in Hiron point. There are also two other Heritage side in Sundarban; one is Kochikhali and the other is Mandarbaria where you will find dears and birds. If you are lucky you can see the Great Royal Bengal Tiger, but for sure you can at least see the stepping of Great Royal Bengal Tiger here and there in these spots.

Karamjol: Karamjol is a forest station for the Rangers. Here you can see a dear breeding center. To visit Sundarban you need to go there with a guide and it is even better if you go there with a group. You can stay two/three days in Sundarban depending on your desire and requirements. One-day tour is not enough for Sundarban as you will not be able to see the nature in haste. For one-day tour you can go up to Karamjol and at a glance visit the outer portion of Sundarban forest areas.

In your Sundarban tour you will be able to see a lots of verities birds (a heaven for the bird watchers), can watch the fishing in the river by the fishermen, if you wish you can ask your tour operator to give a stopover in the fishermen villages to watch their lifestyle, see lots of animals like monkeys, various types deer, foxes, crocodiles, snakes and if you are lucky person you will be able to see the greatest mystery of Sundarban -The Royal Bengal Tiger. Sundarban is one of main sources to collect pure honey. You should not forget to buy some pure honey. Another inexpressible and unforgettable beauty you can enjoy if you can match your timing of tour in full moon. In the full moon the nights in Sundarban could be one of the most memorable nights for your whole life (The Independent, July 26, 2005).

A mangrove forest in death throes Shrimp farmers, land grabbers denuding an island in Cox's Bazar

A large mangrove is in its death throes because of the greed of shrimp farmers. A land grabber syndicate has been annihilating the mangrove forest in Goldia Island of Cox's Bazar. Embankments are being constructed all over the island in order to make shrimp farms.( The Daily Star ). When The Daily Star correspondent visited the area on February 15, approximately 200 workers were seen engaged in chopping down the mangrove forest, moving the timber somewhere else and building embankments for shrimp farms. A vast tract of mangrove forest in Goldia Island of Cox's Bazar has turned completely barren as shrimp farmers chopped down the trees to construct embankments all over the island. The inset shows two persons rowing a boat loaded with logs of trees collected from the mangrove forest.

Kashem Majhi, a labour leader, told The Daily Star that he had been leading 100 labourers to chop down the mangrove forest for the last 10 days. Syedul Haque Shikder of Moheshkhali hired the labourers through him to clear the forest in the island.

Bashi Majhi said he has been constructing embankments for shrimp farms along with some 100 workers for the last seven days. He also said Syedul was having the embankments built.

Shaplapur Forest Office In-charge MA Samad, whose office is just half a kilometre away from Goldia, said when he along with his forest guards went to Goldia Island, the goons of Syedul Haque chased them away from the island. Samad contacted Syedul over cellphone to enquire about the matter and he was told that Syedul took lease of the island and he would show him all relevant documents. But, Syedul never showed up with the documents and continued his destruction of the island's forest.

Samad said according to cadastral survey the land between the lines 18, 21, 23 of Charandip and 2027, 2035 of Rampur has a total area of 150 acres. The forest department carried out a huge forestation programme in 1989 and the trees have now grown up. Hence, the quarter is grabbing the land as well as the trees. Meanwhile the forest department lodged four cases against Syedul with Moheshkhali Police Station. Forest official Faridul Alam said a legal notice was also issued against Syedul recently.

Despite repeated efforts, The Daily Star failed to contact Syedul and talk about the matter. However, Enamul Haque, younger brother of Syedul, contacted The Daily Star and admitted to the ongoing deforestation and embankment building in the island but denied their involvement.

When The Daily Star contacted the deputy commissioner's (DC's) office regarding the issue none agreed to provide any information. However, an official requesting not to be named said on August 1, 2006 the then DC of the district sent a lease proposal to the Ministry of Land for approval. It was approved on October 17, 2006.

Sources claimed the then DC Mohammed Habibur Rahman along with the upazila nirbahi officers (UNO) of Cox's Bazar Sadar and Chakaria and the land officers of Chakaria on August 1, last year surreptitiously gave away lease of Goldia island's land to their relatives and took lease of land through false names.

This lease was approved at the 13th meeting of District Shrimp Development Management Committee. The recipients of the land are 1. Rahela Begum, wife of Abu Rahim, who was a house help to former DC Habibur Rahman, 2. Chand Sultana, wife of Shah Alam, Borang, Khilgaon, Dhaka, 3. Mohammed Anisuzzaman Chowdhury, son of Akchirul Hossain Chowdhury, Charaki, Comilla, 4. Sarkar Altaz Mahmud, son of Iskafil Hossain Sarkar, Fatullah, Narayanganj, 5. Kanij Fatema, wife of Selim Uddin, Lohagara, Chittagong, 6. Mohammed Nurul Alam, son of Sekandar Ali Munshi, Saiddar Nikli, Kishoreganj, 7. Mohammed Nezam Uddin, son of Kutub Uddin, Halishahar, Chittagong, 8. SM Atikur Rahman, son of Mohammed Selim, Komira, Rangpur and 9. Mohammed Maniruzzaman, son of Oahiduzzaman, Tevagiya, Comilla.

On contact, Rahela Begum said, "I did not take lease of any land and I was unaware if someone took lease of land using my name."

The then DC of the district said, "I have not taken lease of any piece of land in the district and if my servant has taken lease of any land that's not my problem."

The forest officials said there is no scope for anybody to take lease of the forest land secretly, as the Ministry of Land in a memorandum dated October 30, 1996 clearly stated that no Khas land shall be given lease to any person without prior approval from the ministry.

Sources said Shrimp Project Development Management Committee decided during its second meeting held on September 1, 2006 that lease proposal must be jointly signed by the union level land and forest officials prior to submitting it to the DC's office. Therefore, the forest officials claim that they did not approve it and the DC had no right to give lease of forestland in such manner.

Sources said Syedul is experienced in grabbing land and the lease takers of Goldia's land invested large amounts of money through him.

Faridul Alam, a forest official, said as per a government memorandum, all newfound islands shall be under the forest department for first 20 years for afforestation (Source: News From Bangladesh, February 22, 2007).

In many areas of the world, mangrove forest is contributing to avert fisheries declines, degradation of clean water supplies, salinisation of coastal soils, erosion, and land subsidence, as well as the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In fact, mangrove forests fix more carbon dioxide per unit area than phytoplankton in tropical oceans. With regard to the Sundarbans, experts have sounded a note of caution that the destruction of the mangrove forest will not only affect the ecology but also cause far-reaching adverse impact on the national economy by immensely damaging to the marine resources of the Bay of Bengal which still remains economically unexplored and unexploited by Bangladesh. The loss of the Sundarbans would also expose the entire south-western region of the country to frequent cyclones and tidal surges.

Mangrove forests once covered three-fourths of the coastlines of tropical and sub-tropical countries. Today, less than 50 per cent of that is surviving. And then again, of this remaining mangrove forests, over 50 per cent has been degraded and not in good form. Greater protection measures should be taken for maintaining high-quality mangrove forests like the Sunbarbans--a world heritage site. All said and done, future sustainability of the Sundarbans depends on the political will of the policy makers, environmental awareness of the people and the improved management and conservation by the forest department and other concerned agencies.

Sunderbans in the firing line

Coal-fired power plants are prodigious polluter of the environment and toxic terror for the people living nearby. Besides greenhouse gases and particulate matter, they produce a host of toxic pollutants – lead, mercury, cadmium, zinc and arsenic, cobalt, manganese and trace amounts of uranium, carbon monoxide, fly ash, bottom ash and volatile organic compounds – which have detrimental effects on human health and the environment. According to the Rainforest Action Network, from the cradle to the grave, coal is a risky business. Each stage in the life cycle of coal -- extraction, transportation and combustion -- presents increasing health [and] environmental risks.”

By deciding to build a coal-fired power plant at Rampal, the Bangladeshi government has embarked on a mission to destroy one of the most ecologically sensitive rainforests in the world -- the Sunderbans. The economic benefits that will result from the construction of the power plant, the prospects of which are in any case highly dubious, cannot compensate for the long term adverse effects it will have on the forest and the local population. Why do we care about the Sunderbans? We care about the Sundarbans because it provides natural protection against rising sea levels and killer cyclones. The trees of the forest act as a sink for greenhouse gases. They abate flooding and moderate the climate. They also help perpetuate the water cycle by releasing water vapor into the atmosphere. More importantly, the Sunderbans is home to a large number of the world's plant and animal species, including many endangered species. It is also home to many rare plants and animals that do not exist anywhere else in the world.

How will the Rampal Power Plant affect the Sunderbans? The pollutants from the power plant will cause deforestation which will contribute significantly to the total global carbon emissions. Deforestation in turn will reduce biodiversity, cause flash floods, increase soil erosion and disrupt livelihood of millions of people.

The anthropogenic degradation of the environment due to the greenhouse gases emitted from the Rampal Power Plant will have harmful effects on the local agriculture, silviculture, aquaculture and eco-tourism. Other pollutants that will directly impact the ecosystem of the Sunderbans and its surroundings are sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, mercury and volatile organic compounds.

Acid rain produced by the reaction of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides with water, oxygen and other chemicals in the air is one of the most serious types of pollution that will affect the Sunderbans. It will cause foliar damage, impair seed germination, dissolve the nutrients in the soil and wash them away before trees and other plants can use them to grow. Acid rain will also harm the forest's animals and wreak havoc on the marine ecosystem. The effects directly due to sulfur dioxide are hard to isolate, however, because particulates and moisture are usually present in the same environment and play a synergistic role. Nevertheless, plants will be affected by sulfur dioxide and trees will suffer appreciable damage to their leaves and internal cells.

Ground-level ozone and smog produced through a complex chain of reactions involving nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds will also have harmful effects on the Sunderbans. Ozone is known to damage the leaves of plants and trees as well as the tissues of living creatures.Mercury, a highly potent neurotoxin and an inevitable by-product of a coal-fired power plant, when released into the atmosphere settles in nearby streams and rivers. It will cause considerable damage to the aquatic ecosystem by polluting the rivers of the region. Mercury will enter the food chain via algae and infect all forms of wildlife, in the rivers and on land, from fish to birds to mammals, whose diet includes fish.

As for the humans, eating fish from mercury polluted rivers can cause severe disability including deafness and blurring of vision, mental derangement, neurological defects and even death. The deadliest episode of mercury poisonings occurred in 1953 among people who ate seafood from Minamata Bay (Japan) into which methyl mercury was released by a chemical factory.

Thermal pollution due to discharge of waste heat into nearby rivers will change the ambient temperature of the water, which could lead to a complete shift from cold- to warm-water forms of life. Whereas such a replacement might cause little disruption to the productivity of a body of water once the adjustment has taken place, in almost no instance would the production of heated effluent be constant for long enough periods to allow either adaptation or replacement to be effective. The effluent will eventually affect not only the aquatic organisms of the Sunderbans, but also the entire ecosystem of the aquatic environment.

Furthermore, thousands of workers driving trucks, operating heavy equipment and barges hauling coal will drive the animals, particularly the tigers, out of their habitats. Also, parts of the forest have to be cleared of trees and plants to facilitate settlements for the workers of the power plant. The cleared area, when exposed to high temperatures, will be paved with hard-packed laterite. Once formed, laterite is almost impossible to break up, and areas that once supported lush forest will, at best, be able to support only shrubs or stunted trees.

Of course, the government's first obligation is to the people. Rampal will surely solve the energy problem, albeit partially. But the truism runs, as fast as old problems are solved, new ones appear. To avoid new problems, we should look to the future with our eyes wide open, rather than narrowly focused on material welfare and convenience. We must be on the side of nature while we dream and scheme, because we are part of nature. To view ourselves as separate from nature is an abstraction which in reality does not exist. Our continued existence depends not just on rice, fish, fowl and cows, but on the continued well-being of all the plants and animals on Earth.

By ignoring the impact Rampal Power Plant will have on the Sunderbans, people in power are portraying nature as an adversary which can be tamed with technology, an adversary against which we must constantly struggle. This is clearly a reflection of their short-sighted, anthropocentric view of the environment; a manifestation of myopia and an abysmal ignorance of the interrelatedness of humans, plants, animals and their environments.

There is still time to take a rational approach to the power shortage problem and chose an alternate site which will have minimal effect on the environment. By doing so, some semblance of the natural world will be preserved. Otherwise, we would be sacrificing the enormous value of a standing rainforest for a short-term economic benefit that will consume much more than it will produce.

Finally, nature not only abhors vacuum; nature abhors human interference too. A true wilderness should be viewed bio-centrically. The forests should be free to burn, free to be blown away by storms, free to be washed away by floods and free to be attacked by insects. These are natural events to which forests are adapted to respond. The new forests that will emerge may be different from the old ones, but that is the way things change in a natural ecosystem. (Quamrul Haider Fordham University, New York, Daily Star 18. 08. 14).Sundarbans Environmental and Livelihood Security (2010-2014)

Interestingly, the Indian government does not allow construction of such plants in its own territory. Their recently enacted ‘EIA guidelines for thermal power plant 2010' forbids this kind of development activity within 25 km of the officially declared forest boundaries. The Indian government is unfortunately violating its own law at Rampal taking advantage of the loopholes that exist in Bangladesh forest laws.

The major objective of all these projects is to generate sources of alternative livelihood for the forest-dependent poor people. Thus, the question is, why do we still need to have a power plant to save the Sundarbans from the ‘clutches’ of the poor despite the presence of those projects? The claim that the poor communities living in the forest area grab land for their livelihood does not have any merit.

We do not require rocket science to understand the potential risks of developing Dhaka city compromising with the long term necessity of conserving the Buriganga river and the other important water bodies. Why are we sacrificing those precious gifts of nature for urban ‘development’? Dhaka is now the second most uninhabitable city on earth! There are many alternatives ways of energy production, but the Sundarbans is unique. It is neither a village nor a residential area. It is a government-declared ecologically critical area, World Heritage site, as well as a Ramsar site that requires extra caution and protection. This is also not a property that belongs only to Bangladesh; it is a natural asset of the whole of mankind. We expect that good sense of official policy makers of both Bangladesh and India will prevail and they will take all the needful measures to cancel the Rampal power plant to save the Sundarbans, the living defender, to protect Bangladesh from cyclones and other disasters (Daily Star, Sept 23, 2013).

The irony is, those who have been resisting the environmentally degrading power plant are being dubbed either as ‘anti-development’ or as ‘utopians.’ This is in fact not a new phenomenon. A common perception is that this group of people does not have any clue about any alternative, nor has any idea of how to economically advance the country. To these so-called ‘messiahs’ of development, the effort to save nature is only a luxury that Bangladesh cannot afford at this moment. Their preferred strategy of development is to “pollute first, and clean up later.” But while advocating such strategy, they forget that the philosophy of modern development has undergone a fundamental shift in the last few decades.

Tracking the global ruins of ‘modernisation’ and traditional ‘development,’ the new generation of development scholars argues that the environment and development are inseparable; their interconnection is no longer a mere fantasy. They understand development as an integrative term. To them, development ignoring social and environmental concerns is indeed an emblem of narrow and visionless thoughts.Oil spill - Time runs out

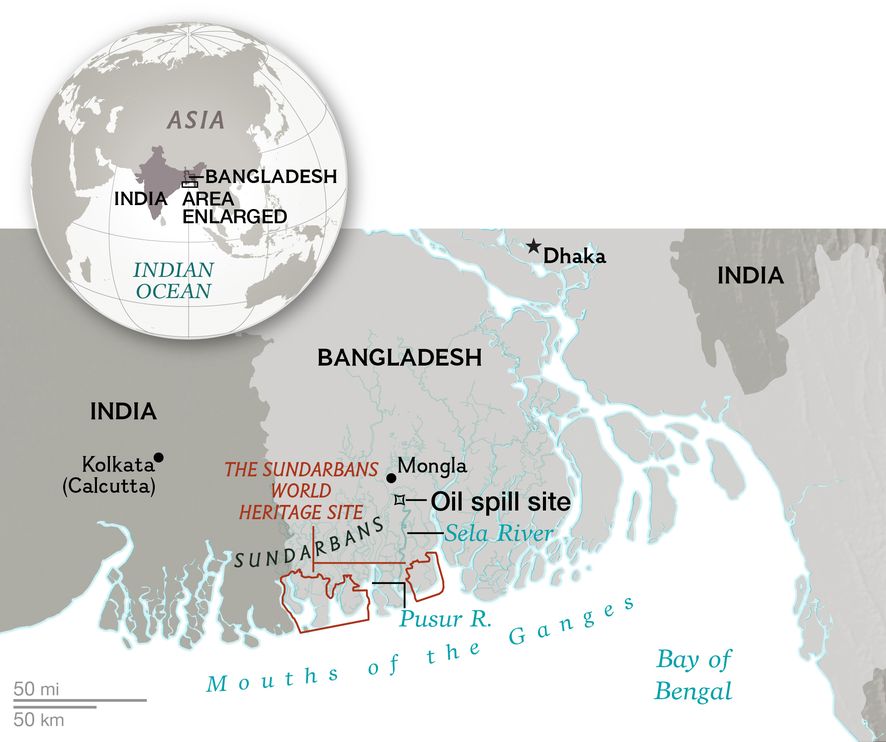

Friday, 12 December 2014 - Despite passage of three days no tangible step was initiated by authorities to remove the oil spilled from the tanker into the Shela River and adjacent canals flowing through the Sundarbans. Causing concern over the delay, environmentalists said it would intensify the catastrophe the mangrove forest is facing due to the massive spill. The oil tanker, Southern Star-7 that sank early on Tuesday, spilling 357,668 litres of furnace oil, was salvaged at noon yesterday.

The owner of the capsized tanker, started rescue works around 10.30am Thursday. It was towed with the help of four rescue vessels to sandbar at Joymoni area. The authorities said they plan to remove the huge oil slick, that poses a threat to the biodiversity across 34,000 hectares in the protected mangrove forests, in the next three days.

Kandari 10, equipped with dis-percent, a chemical that dissolves oil into foam, reached to the accident site, while the other two rescue vessels of the Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA) are yet to reach the spot. Forest officials suspect that all of the 350,000 litres of furnace oil from the sunken tanker has spread to all rivers and their tributaries and canals of the Sunderbans over an area of 80 km.

Villagers will suck oil floating in the river water in the next three days to help clean the Shela, BIWTA chairman Samsuddoha Khondaker told reporters.

“At the moment, spraying of the chemical dis-percent won’t be allowed. The authorities will take a decision after three days whether to use chemical sprays from Kandari-10,” he said.

Forest department sources said it would require the permission of the higher authorities to use the chemical, considering its impact on the biodiversity of the forest and aquatic lives.In the wake of the oil spillage following Tuesday’s collision between a tanker and a cargo vessel that is now threatening the ecosystem of the Sundarbans, environmental campaigners are now questioning the role of the relevant authorities in safeguarding the world’s largest mangrove forest. An environment lawyer told The Independent that the Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA) should be held responsible for authorising vessels to use a channel inside the protected mangrove area, particularly at night. Syeda Rizwana Hasan, executive director of Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association, said the oil tanker, as well as the cargo vessel that hit it, were on the Shela River channel despite a ban on night travel. Anticipating a major eco-disaster, environmental groups had repeatedly requested the authorities to close the Shela passage, which was opened as an alternative route after the Ghashiakhali channel was abandoned three years ago due to excessive siltation (The Independent, 11. 12. 14).

Containing the Sundarbans oil spill

WITH plant and animal life dying as the water hyacinth of Shela and Pashur rivers turn black with the oil spill, the only steps taken by authorities has been the raising of the sunken vessel. People of the locality have been advised by Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA) to collect the furnace oil using fishing nets, sponges and any other “manual” means. We are appalled at the lack of movement on the issue of clean up operation which needs to commence immediately to preserve the mangrove forest and its ecological diversity. Going by what has been reported in the press the navy is supposed to spray a powder adhesive to increase the density of the oil which could then be swept up by fishing nets. That plan apparently has stalled as requisite permission is still pending with the Department of Environment (DoE).

While the government has formed two bodies to investigate the oil spillage and make damage assessment and the “negative” impact of spraying oil spill dispersant, every day's delay is allowing the oil spill to spread to another 10-15 km area. And it is not only flora and fauna that are dying. Thousands of people who make a living off the forests and waterways of the Sundarbans are witnessing an end of their livelihoods. It is imperative that the DoE waste no more time to check the powder adhesive compound's chemical composition and whether it conforms to all international safety standards before using it in the affected area (Daily Star, Editorial 13. 12. 14).

After Oil Spill in Bangladesh's Unique Mangrove Forest, Fears About Rare Animals

More than 90,000 gallons of oil have spilled into the rivers and creeks of the Sundarbans region, threatening tigers, dolphins.

Oil from a wrecked tanker is creating a disaster in the waters of Bangladesh's Sundarbans, the largest contiguous tidal mangrove forest in the world and a haven for a spectacular array of species, including the rare Irrawaddy and Gangetic dolphins and the highly endangered Bengal tiger, reports the National Geographic. "This catastrophe is unprecedented in the Sundarbans, and we don't know how to tackle this," Amir Hossain, chief forest official of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, told reporters.

Named for the native sundari tree, the Sundarbans is a vast delta of densely forested, mangrove-fringed islands threaded by an intricate network of creeks and channels, or canals. The delta is a UNESCO World Heritage site that encompasses some 3,850 square miles (1,000 square kilometers), with roughly one-third lying in India and two-thirds in Bangladesh.

On both sides of the border, densely populated villages abut protected areas set aside for the region's extraordinary biodiversity

In the early hours of December 9, in dense fog, the tanker Southern Star 7, carrying some 92,000 gallons of bunker oil, was rammed by a cargo vessel in the Sela River, at the entrance to the Bangladesh Sundarbans, southeast of the river port of Mongla. The collision occurred inside the Chandpai dolphin sanctuary.

Seven crew members survived by jumping ship and swimming to shore. The body of Captain Mokhlesur Rahman was retrieved five days later. Reportedly, some 52,000 gallons of fuel has already leaked into the brackish tidal water. According to Hossain, the spill has spread over a 40-mile-long (64 kilometers) area along the Sela and Pusur Rivers.

Official announcements have not yet clarified the extent of the damage. News footage shown on local television has revealed lines of oil-blackened shoreline and mangrove trees bearing a high-tide mark of black oil. In television interviews, villagers and fishers have complained of the smell of oil. Sightings of dead fish and crabs have been reported in the Chandpai region's channels.

Remote and hard to get to except by water, the Sundarbans is a place of wild, menacing beauty. Here, jewel-like kingfishers may perch above a sleeping estuarine crocodile or fly over the fin of a passing shark.

At low tide, otters, monkeys, wild boars, and spotted deer emerge from the forest, and the mud banks regularly bear the deep pugmarks of a striding tiger. Bird life is famously prolific, with more than 300 different species known to live in the area.

In 2011, the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society discovered a remarkable population of 6,000 Irrawaddy dolphins in the Bangladesh Sundarbans.

The find led to the creation of three sanctuaries for Irrawaddy and long-nosed Gangetic dolphins. The fact that the oil tanker was wrecked in one of the sanctuaries has heightened the grave concerns about the environmental impact (Daily Star, December 17, 2014).SILENT CRY OF THE SUNDARBANS

Mismanagement and negligence is leading to the destruction of one of the world's last wildlife sanctuaries

Bangladesh's last environmental sanctuary, the largest contiguous mangrove forest on earth, Sundarbans is dying. Its death sentence has been confirmed by the industrialisation of the adjacent area especially after the beginning of the construction of Rampal Power Plant; a massive coal fired power plant only 14 km away from the forest. As a result, wild rivers and creeks of the once impenetrable Sundarbans have turned into a popular route for cargo vessels and oil tankers. The rumbling noise of the diesel engines and higher powered search lights of these vessels have also been driving wild animals away from their last remaining sanctuary in the country. A disaster was inevitable. And that disaster took place on December 9, 2014. Collision between a cargo vessel and the oil tanker Southern Star VII resulted in a massive oil spill. 350,000 litres of furnace oil spread over 10,000 square kilometres of this mangrove forest creating a black coat of oil over the rivers, shores and the forest floor. Amir Hussain, chief forest official of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, informed reporters, “This catastrophe is unprecedented in the Sundarbans and we don't know how to tackle it.”

Nowadays, the occurrence of oil spills and its effective management is not too uncommon or difficult. The Bangladesh government did not use chemical dispersants to avoid further contamination but there are other more feasible ways that can be considered. Dr Imam commented, “There are available modern technologies like booms, skimmers, sorbents which can be obtained from many countries to tackle this disaster. Using manual labour to remove oil is outdated and ineffective.” But the question is how can we save the Sundarbans when the government is not recognising this disaster at all?

We have been observing practical examples of Hussain's frank apology for 11 days. While hundreds of animals, including rare species like the Irrawaddi dolphins, are dying due to the oil spill, the only noticeable measure taken by the government to recover from this disaster is a manual clean-up of the spilled oil. Government's buy-back plan to purchase the leaked oil at Tk 30 per litre has pushed thousands of local villagers to collect it from the rivers and the forest. These villagers, including children, are collecting the oil without any protective clothing, using kitchen utensils, shovels and sponges. Research shows that long term exposure to benzene, the most common and toxic ingredient of furnace oil, can cause leukaemia. Dr. Badrul Imam, Professor of Geology Department, University of Dhaka commented that toxic chemicals of furnace oil can also cause skin cancer, and lung, kidney and liver damages depending on whether the chemicals are touched, inhaled or eaten. People are also cutting down trees indiscriminately to collect the oil accumulated on the roots and barks of the trees.

Ten days after the disaster, environment minister Anwar Hossain Manju paid a half an hour visit to the spot, saying, “The extent of damage is not as much as we had anticipated. Some oil coated trees and herbs of the river banks will die but they will grow again next year, as our Chief Conservator of Forests said.” (December 19, 2014 The Daily Prothom Alo) Similar comments were made by the Shipping Minister Shahjahan Khan who denied the fact of fatal consequences. In fact reports say that the cargo vessels and oil tankers are still using the Shela River, the spot of the accident, and other channels inside the forest at night ignoring the government's order not to use them. On top of that, the government is going to establish another 150 MW furnace oil fired power plant in Mongla, which is within striking distance from Sundarbans. (December 21, The Daily Kaler Kontho)

Whether our government admits it or not, the fact is that the Sundarbans is getting destroyed. Plants and animals are dying, breeding has stopped and many animals are leaving the Bangladeshi parts of the Sundarbans.

Scavengers like vultures and kites are seen flying over the forest constantly indicating that animals are dying deep inside the forest. Junaid K Choudhury, who has been researching on mangrove forests and the Sundarbans for 25 years, told the Prothom Alo, “Among all kinds of forests, mangrove is the most susceptible one. This oil spill can cause damage that we will not be able to identify in two to three months even in two to three years. Perhaps after 10 years we will discover that a particular species was lost from this forest forever thanks to the oil spill.”

The Sundarbans not only shelters some of the rarest species of animals in the world but also saves us from coastal super cyclones like Sidr. Bangladesh's survival depends on the survival of the Sundarbans. The damage has already been done. But to prevent further occurrences we must come forward to prevent tne destruction of this life bowl. Not only the Shella river, but all the waterways inside the forest have to be protected from commercial navigation. Power plants and industries have to be relocated to safer distances from the forest. Otherwise, there will be no Sundarbans in the near future and the consequences of that will be dire. (Daily Star 31. 12. 14)Climate Change-

Sundarbans, low-lying areas might go under water within 50 yearsFood production reduced significantly, the Sundarbans is losing its greenery, public health is deteriorating day by day, the Mongla seaport is becoming dead and the southwest coastal areas is being frequently affected by natural disasters due to climate change. Locals told these at the BBC Bangladesh Sanglap held on the bank of the river Pashur near the Sundarbans in Khulna yesterday.